ALSO BY MARVIN W. MEYER

The Mithras Liturgy

(editor and translator)

The Letter of Peter to Philip

Who Do People Say I Am?

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, June 1986

Copyright 1984 by Marvin W. Meyer

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published, in hardcover, by Random House, Inc. in 1984.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nag Hammadi codices. English. Selections.

The secret teachings of Jesus.

Reprint. Originally published in hardcover by

Random House, Inc. in 1984.

1. Gnosticism. 2. Jesus ChristTeachings. I. Meyer,

Marvin W. II. Title.

BT1390.N33213 1986 229.8052 85-40864

eISBN: 978-0-307-75664-0

v3.1

To Stephen and Jonathan

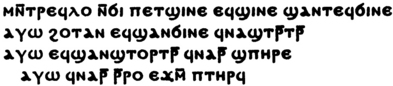

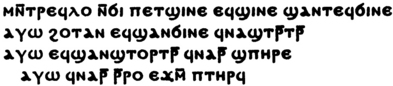

Gospel of Thomas saying 2

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my appreciation to several people who have assisted in the preparation of this book. The Institute for Antiquity and Christianity of Claremont Graduate School, and the Institutes director, James M. Robinson, provided a supportive context for my study of the Nag Hammadi texts translated and interpreted here. The availability of the photographic and bibliographical resources in the Institutes Nag Hammadi archive greatly aided my translational work. I have discussed portions of the translationscommonly the most difficult and perplexing passageswith students and colleagues, especially in the Claremont Coptic texts seminar, and to these friends I extend my thanks. Elaine H. Pagels, James M. Robinson, and Richard Smith have seen the entirety of the manuscript in an earlier draft, and their comments have proved particularly useful.

I also wish to acknowledge the painstaking editorial work of Beverly Haviland and Laura Schultz at Random House, and the skillful word-processing of Deborah De Golyer.

Finally, I offer my most profound expression of gratitude to my wife and children, whose loving encouragement and patience have been indispensable for the completion of this project.

Marvin W. Meyer

Ferrum College, Virginia

Contents

Introduction

In December 1945, two Egyptian fellahin were riding their camels, searching for natural fertilizer along the base of the magnificent cliffs that grace the Nile River as it flows around the great river bend in Upper Egypt. As one of these farmers, Muhammad Ali al-Samman Muhammad Khalifah, tells the story, they hobbled their camels and began to dig near a large boulder that lies at the foot of an exceptionally impressive cliff called the Jabal al-Tarif. Suddenly they struck something hard. They dug farther and unearthed a sealed storage jar that had lain there in the sand of Egypt for hundreds of years. At first Muhammad Ali feared to open the jar, lest he release a jinn, or spirit, imprisoned inside. Then he wondered whether the jar might not contain gold, just as other containers discovered a few kilometers upstream at the Valley of the Kings had yielded gold and treasures. His love of gold overcame his fear of jinns, and he did break open the jar. According to Muhammad Ali, indeed there was gold inside: it flew out of the jar and ascended to the sky, leaving only a collection of old papyrus books for him to throw onto his camel and take home.

The gold that Muhammad Ali saw was probably tiny papyrus fragments. Bits of papyrus, golden in color and glistening in the sun, could easily be mistaken for flecks of gold by one who hoped to find treasure. As disappointed as he might have been that day, Muhammad Ali found a real treasure, more valuable, perhaps, than a jar full of gold: a collection of ancient manuscripts, now called the Nag Hammadi library. This manuscript discovery consists of thirteen codices, or books, containing some fifty-two texts, the majority of which were previously unknown. Most of the texts reflect a mystical, esoteric religious movement that we term Gnosticism, from the Greek word gnosis, knowledge. These texts are also, with a few exceptions, Christian documents, and thus they provide us with valuable new information about the character of the early church, and the Gnostic Christians within the church, during its first, formative centuries.

The Nag Hammadi manuscripts are giving us an increasingly clear perception of the Gnostic movement. Gnostics emphasized the quest for understanding, but not a common, mundane understanding; they searched for a higher knowledge, a more profound insight into the deep and secret things of God. Like other mystics, Gnostics admitted that this saving knowledge cannot be acquired through the memorization of phrases or the study of books; nevertheless, like other mystics, they composed numerous documents explaining the nature of spiritual gnosis. Such Gnostic texts proclaim a completely good and transcendent God, whose enlightened greatness is utterly unfathomable and essentially indescribable. Yet this divine Other can be experienced in a persons inner life, for the spirit within is actually the divine self, the inner spark or ray of heavenly light. The tragedy of human existence, however, is that most people fail to realize the fulfillment of the divine life, because of the harsh world that functions as the stage for the human drama. The Gnostics understood this mortal world, with all its evils and distractions, to be a deadly trap for one who seeks knowledge. Moreover, the divine spirit is imprisoned by the passions of the sensual soul and the elements of the fleshly body. Gnostic texts employ various figures of speech to depict the sorry fate of the entrapped spirit: it is asleep, drunk, sick, ignorant, and in darkness. In order to be liberated, then, the spirit needs to be awakened and brought to sobriety, wholeness, knowledge, and enlightenment. This transformation in ones life, Gnostics maintained, is accomplished through a call from Godthe God without and withinto discover true knowledge and rest. For Gnostic Christians, the source of the divine call is Christ.

We can see why many Gnostics were considered dissidents in the ancient world. They called into question the values of civilized society and instead fostered spiritual values and lifestyles. Some radical Gnostics apparently retreated from the world to the solitary life of the monk or the ascetic, and refused to participate in the everyday business of human society. Other equally radical Gnostics seem to have flaunted their disdain for conventional human values by disregarding the amenities of polite society and practicing a libertine way of life. Most Gnostics, however, probably led normal lives in society, while engaging in an inner, spiritual quest for God. Within the church, too, Gnostic believers often advocated a faith and life quite different from what church leaders were promoting. Gnostic Christians challenged the authority of the priests and bishops and suggested that a spiritual, Gnostic life devoted to a spiritual, Gnostic Christ allowed them to approach and embrace God directly. For their stance Gnostic Christians were eventually condemned as heretics in the debates about orthodoxy and heresy that raged within the early church, and most of their books were suppressed or destroyed by their triumphant opponents.