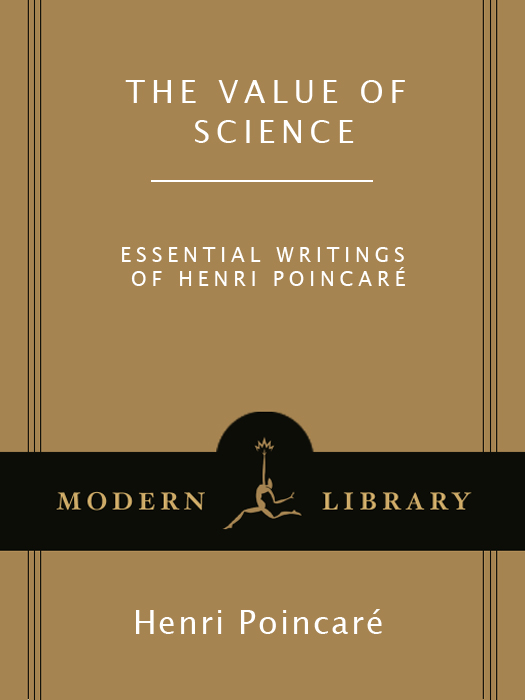

2001 Modern Library Paperback Edition

Biographical note and compilation copyright 2001 by Random House, Inc.

Series introduction copyright 2001 by Stephen Jay Gould

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Modern Library, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

M ODERN L IBRARY and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This work is comprised of three seperate volumes by Henri Poincar: Science and Hypothesis (1905), The Value of Science (1913), and Science and Method (1914).

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Poincar, Henri, 18541912.

[Selections. English]

The value of science : essential writings of Henri Poincar /

Henri Poincar.

p. cm. (Modern Library science series)

eISBN: 978-0-307-82406-6

1. SciencePhilosophy. 2. ScienceMethodology. 3. MathematicsPhilosophy. I. Title. II. Modern Library science series (New York, N.Y.)

Q175.P7815213 2001

501dc21 2001030834

Modern Library website address: www.modernlibrary.com

v3.1

I NTRODUCTION TO THE M ODERN L IBRARY

S CIENCE S ERIES

THE NATURAL STATUS OF SCIENCE AS LITERATURE

Stephen Jay Gould

I have never quite figured out why standard college courses on Victorian literature invariably include Charles Dickens and George Eliot (as they should), but almost invariably exclude Thomas Henry Huxley and Charles Lyell, who wrote just as well, albeit in the different genre of science. Anyone who has accepted, passively and without personal examination, the conventional caricature of scientific writing as boring, inaccessible, illiterate, or unreadable might just consider Lyells indictment, from the early 1830s, of catastrophism in geology, and his defense of the uniformitarian view that current causes, acting at their modest and observable rates throughout the immensity of geological time, can build the full panoply of earthly events, from Grand Canyons to Himalayan Mountains. (I dont even agree with Lyells conclusion, for we now know that catastrophic impacts cause at least some mass extinctions, but I admire the literary quality of his largely correct assessment of old-style speculative catastrophismeven down to the slightly forced unsplit infinitive of the last line):

Never was there a dogma more calculated to foster indolence, and to blunt the keen edge of curiosity, than this assumption of the discordance between the former and existing causes of change. The student was taught to despond from the first. Geology, it was affirmed, could never rise to the rank of an exact science. [With catastrophism] we see the ancient spirit of speculation revived, and a desire manifestly shown to cut, rather than patiently to untie, the Gordian Knot.

I would not claim, of course, that all science, or even science in general, appears in print as good writing. After all, literary quality does not rank high as a criterion (or even as a recognized property) for most editors of scientific journals, or for most practitioners themselvesand felicitous writers, as students, generally receive strong pushes, from their early teachers, towards the arts and humanities. Moreover, and for some perverse reason that I have never understood, editors of scientific journals have adopted several conventions that stifle good prose, albeit unintentionallyparticularly the unrelenting passive voice required in descriptive sections, and often used throughout. The desired goals are, presumably, modesty, brevity, and objectivity; but why dont these editors understand that the passive voice, a pretty barbarous literary mode in most cases, but especially in this unrelenting and listlike form, offers no such guarantee? A person can be just as immodest thereby (the discovery that was made will prove to be the greatest ); moreover, the passive voice usually requires more words (the work that was done showed ) than the far more eloquent direct statement (I showed that ).

Nonetheless, and even within these strictures of Draconian editing and self-selection of people with little concern for literary quality into the profession, a remarkable amount of good writing does sneak into the pages of our technical journals. For example, the most famous short paper of modern science, Watson and Cricks announcement of the structure of DNA in 1953, begins with a crisp and elegant statement in the active voice (and certainly with requisite, if false, modesty): We wish to suggest a structure for the salt of desoxyribose nucleic acid. The paper then ends with a lovely use of a classical literary device (understatement), invoked here to lay claim to a significant conclusion of equal importance to the discovery itselfan elucidation of the mechanism of replication, or self-copying, by DNA moleculesthat the authors had inferred from the structure but had not yet proven: It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing mechanism we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.

In any case, we need hardly mine the technical literature to find works of sufficiently high literary quality and intellectual importance to merit inclusion within the Modern Library Science Series. After all, the parallel genre of popular science writing has developed, akin and apace, with technical publication. I do not speak of quick journalistic reads, hastily composed, consciously dumbed-down and hyped, and usually written by nonscientists without the requisite feel for the ethos of lab or field life in daily practice. Such works abound, and deserve their quick and permanent obsolescence. Rather, I speak of the fine literary skills possessed by several excellent scientists in each generation (not nearly a majority, of course, but we need representation, not saturation, and a little elitism is not a dangerous thing in this realm). These people write books of high literary quality and intellectual contentvolumes accessible to all, and addressed equally to scientific peers and to a celebrated abstraction, doubted by some, but who really exist in large numbers, the intelligent layperson (again, far from a majority, but we Americans are 300 million strong, so even just a few percent of interested folks will buy more than enough books to justify the bottom line of the enterprise).

The books in this series represent excellent examples of this important genre, spanning literature and science, readable by all, and written by leading experts who did the original work in their technical fields. Thus, this series does not try to develop a compendium of the most influential works of science, in order of their putative importancefor some obvious contenders, Newtons Principia, for example, are truly inaccessible to general audiences. Similarly, we do not present a compendium of the best literature about scientific subjects, for some of these works display more style than content. Rather, we include in this series important books that stand both as landmarks of original scientific accomplishment and as highly readable works of substantial literary skill, explanatory depth and clarity.

The exclusion of some obvious candidatesDarwins Origin of Species comes first to mindonly records their continued and ready availability in good and inexpensive editions by other publishers. (Over the years, many of my graduate students in evolutionary biology, after reading and enjoying Darwins