THE BODY INCANTATORY

THE SHENG YEN SERIES IN CHINESE BUDDHIST STUDIES

THE SHENG YEN SERIES IN CHINESE BUDDHIST STUDIES

CHN-FANG Y, SERIES EDITOR

Following the endowment of the Sheng Yen Professorship in Chinese Buddhist Studies, the Sheng Yen Education Foundation and the Chung Hua Institute of Buddhist Studies in Taiwan jointly endowed a publication series, the Sheng Yen Series in Chinese Studies, at Columbia University Press. Its purpose is to publish monographs containing new scholarship and English translations of classical texts in Chinese Buddhism.

Scholars of Chinese Buddhism have traditionally approached the subject through philology, philosophy, and history. In recent decades, however, they have increasingly adopted an interdisciplinary approach, drawing on anthropology, archaeology, art history, religious studies, and gender studies, among other disciplines. This series aims to provide a home for such pioneering studies in the field of Chinese Buddhism.

Michael J. Walsh, Sacred Economies: Buddhist Business and Religiosity in Medieval China

Koichi Shinohara, Spells, Images, and Mandalas: Tracing the Evolution of Esoteric Buddhist Rituals

Beverley Foulks McGuire, Living Karma: The Religious Practices of Ouyi Zhixu (15991655)

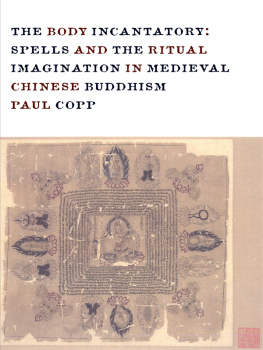

THE BODY INCANTATORY:

SPELLS AND THE RITUAL IMAGINATION IN MEDIEVAL CHINESE BUDDHISM

PAUL COPP

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

PUBLISHERS SINCE 1893

NEW YORK CHICHESTER, WEST SUSSEX

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53778-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Copp, Paul F., 1965- author.

The Body incantatory : spells and the ritual imagination in medieval Chinese Buddhism / Paul Copp.

pages cm. (The Sheng Yen series in Chinese Buddhist studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16270-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-53778-0 (electronic)

1. Buddhist incantationsHistory. 2. BuddhismChinaRitualsHistory. I. Title.

BQ5535.C67 2014

294.3'438dc23

2013036862

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Jacket Image: Madame Wei Mahpratisar amulet. Eighth century? Yale University Art Gallery (Tantric Buddhist Charm, 1955.7.1a). Hobart and Edward Small Moore Memorial Collection, bequest of Mrs. William H. Moore. Ink and colors on silk. 21.5 cm 21.5 cm.

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

For Anna

If one holds it to be self-evident that man is gratified by his fantasy, then one must consider that his fantasy is not like a painted picture, or a plastic model, but a complicated construction of heterogeneous components: words and images. Then one would not place operations with written and spoken signs in opposition to operations with mental images of events.

We must plow through the complete language.

LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN, Remarks on Frazers Golden Bough

I SING the Body electric;

The armies of those I love engirth me, and I engirth them;

They will not let me off till I go with them, respond to them,

And discorrupt them, and charge them full with the charge of the Soul.

Was it doubted that those who corrupt their own bodies conceal themselves;

And if those who defile the living are as bad as they who defile the dead?

And if the body does not do as much as the Soul?

And if the body were not the Soul, what is the Soul?

the body itself balks account.

WALT WHITMAN, Leaves of Grass [1881 ed.]

CONTENTS

Perhaps a bronze pot may have shaped early modes of thought as much as the other way around?

Martin J. POWERS, Pattern and Person: Ornament, Society, and Self in Classical China

When Chinese of the late medieval period (ca. 6001000 CE) turned to Buddhist practices for healing, for relief from the hardships of this life and the next, or for the utter transformations of body and spirit promised in them, one resource was the religions great store of incantations. Spells, in fact, were among Buddhisms most popular elements. As chanted tones, they were central features of the ritual practices of all traditions, whether in grand communal ceremonies, in the quieter daily liturgies of individual monks and laypeople, or in the therapeutic techniques of traveling priests and ritualists. Incantations were equally popular as written texts, in forms such as amulets printed on paper and worn hidden on the body, or as inscribed stone pillars set high on hills, in monastic courtyards, or within tombsforms attested in archeological finds across the length and breadth of the Tang Empire (618907) and through the tenth century. This book covers all forms of Buddhist incantation techniques practiced in this age, but it is mainly about Chinese images and uses of the members of one genre of spell, dhra (Ch. tuoluoni, zongchi, et al.), particularly the ways they were imagined and used in written forms. Like other Buddhist spells in China, dhras were Indic incantations transliterated into Chinese syllables (though sometimes translated) whose powers were said to range from the cure of toothache and armpit odor to the guarantee of future awakening as a buddha. Nearly ubiquitous in Mahyna Buddhist literature, spells were prominent features of Buddhist practice in medieval China and from there across East Asia. Dhras were included in early Mahyna scriptures such as the Lotus Stra to bless and protect those who propounded these radically new and controversial texts. Incantations were given similar roles in the liturgies evidenced in the breviary-like booklets discovered among the manuscripts and xylographs at Dunhuang, the great caravanserai and Buddhist center that served as a doorway in and out of medieval China. In these collections, incantations usually begin or end chanting programs consisting also of prayers (or vows, yuanwen) as well as short passages from long scriptures and/or short scriptures, such as the Heart Stra, in their entireties.

Perhaps most famously, dhras were central elements of the ceremonies of Esoteric, or Tantric, Buddhism, by which for the purposes of this book I mean in particular the systems of ritual-philosophical practice that in mid and late Tang China centered on the Mahvairocana, Susiddhikara, and Vajraekhara (a.k.a. Sarvatathgatatattvasamgraha) scriptures as explicated and elaborated by the priests ubhakarasiha, Vajrabodhi, Amoghavajra, and their disciples, lineages that in the Tang flourished most importantly in the Qianfu, Daxingshan, and Qinglong monasteries of the capital Changan and the Jinge monastery of Mt. Wutai. In later centuries, these Chinese ritual dispensations took root (and grew) most successfully in Japan, while later Indic forms of Esoteric Buddhism established themselves most importantly in Tibetan cultural spheres. In both cases, the traditions are often considered to form a separate vehicle of Buddhist practice: the Vajrayna. In such contexts, dhras were often the main event of a rite; indeed, certain examples, such as the Zunsheng zhou, the Incantation of Glory (the Chinese version of the Uavijaya)one of the spells whose Tang history of practice this book takes as a focusbecame the centers of Esoteric subtraditions of their own, particularly in Tibetan religious spheres. As this book will explore, however, older dhra traditionsperhaps especially in medieval China, in the centuries before the distinctive dhra-deity cults become widespread around the turn of the second millennium CEconstituted a vibrant heritage of their own, with its own logics and histories quite apart from those of the high Esoteric traditions. Indeed, a principal goal of this book is to explore relatively neglected elements in the history of Buddhist incantation practice in China, practices that have been considered poor relations of those of the more glamorous lineages of high Esoteric Buddhism preeminent in the imperial capitals of the middle and late period of the Tang Dynasty.

NEW YORK

NEW YORK