i

Precepts, Ordinations, and Practice

in Medieval Japanese Tendai

2022 Kuroda Institute

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Printing, 2022

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Groner, Paul, author.

Title: Precepts, ordinations, and practice in medieval Japanese Tendai /Paul Groner.

Other titles: Studies in East Asian Buddhism ; no. 31.

Description: Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2022. | Series: Studies in East Asian Buddhism; 31 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021050474 | ISBN 9780824892746 (hardback) | ISBN 9780824893293 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9780824893309 (epub) | ISBN 9780824893316 (kindle edition)

Subjects: LCSH: Tiantai BuddhismJapanHistoryTo 1500. | Monastic and religious life (Buddhism)JapanHistoryTo 1500. | Buddhist preceptsHistoryTo 1500. | Ordination (Buddhism)JapanHistoryTo 1500.

Classification: LCC BQ9144.4.J3 G76 2022 | DDC 294.3/92dc23/eng/20211228

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021050474

The Kuroda Institute for the Study of Buddhism is a nonprofit, educational corporation founded in 1976. One of its primary objectives is to promote scholarship on the historical, philosophical, and cultural ramifications of Buddhism. In association with the University of Hawaii Press, the Institute also publishes Classics in East Asian Buddhism, a series devoted to the translation of significant texts in the East Asian Buddhist tradition.

University of Hawaii Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources.

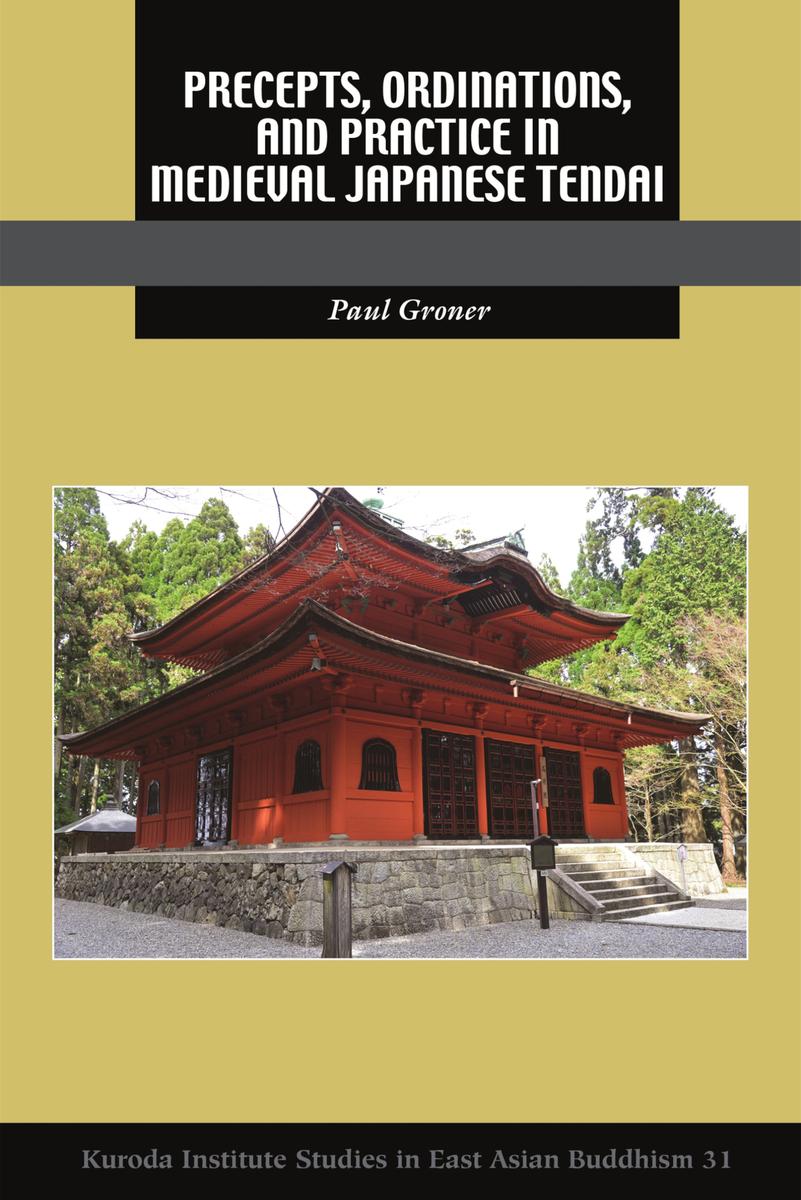

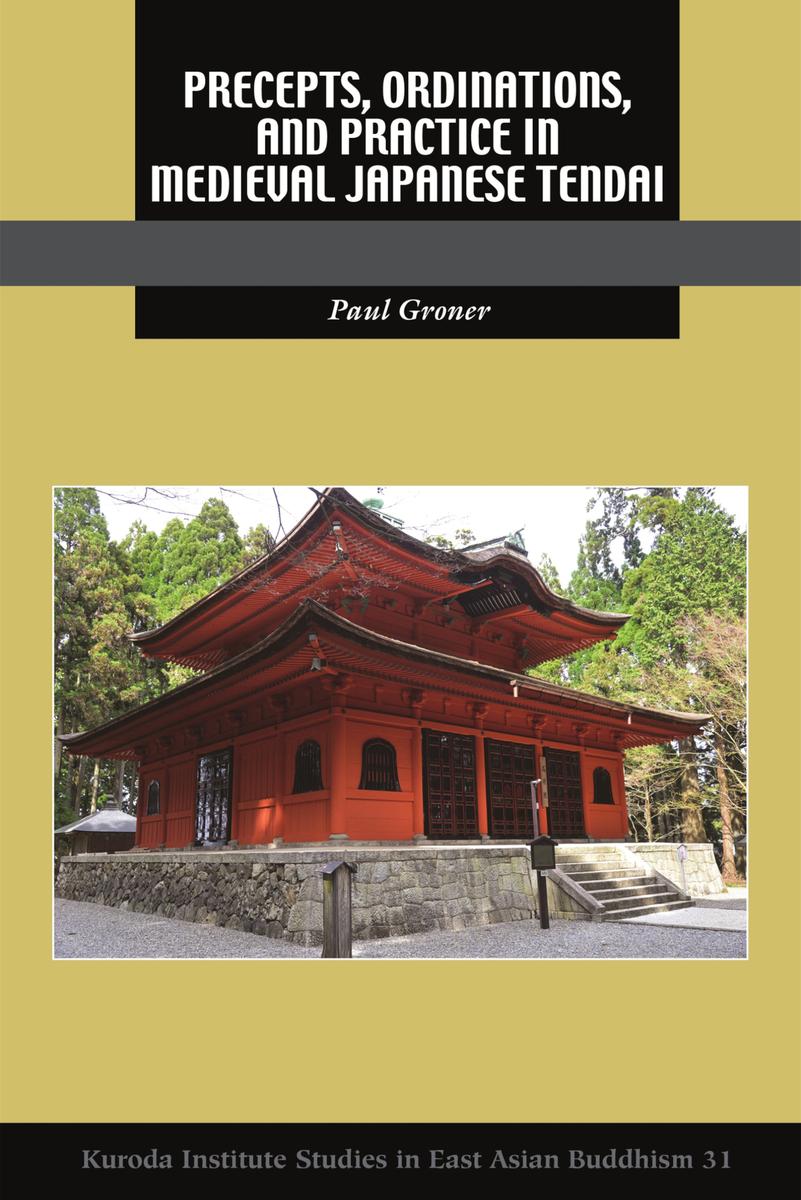

Cover photo: Built in 828, the Precepts Platform Hall is symbolic of the establishment of the Tendai School, the conferral of the precepts by the Buddha, and the transmission of the precepts by leaders of the school.

The current building dates from 1678. Photo courtesy of Enryakuji.

v I dedicate this book to all the teachers and friends in Asia and the West who have taught, inspired, and accompanied me in my studies. Without you, this book would not have been possible.

P ersons going to Japan for the first time to learn about Buddhism are often struck by the worldly lifestyles of Japanese clerics. Most do not keep the monastic precepts but, rather, marry, eat meat, drink alcohol, and lead lives differing little from those of laypeople. Monastics elsewhere in the Buddhist world sometimes consider Japanese Buddhism inauthentic for this reason. Standard overviews attribute this state of affairs to the Meiji governments 1870s legislation that abolished special status for clerics, incorporated them into the household registry system as ordinary citizens, and decriminalized clerical marriage. However, issues surrounding the preceptsthe Buddhist moral and behavioral normshave a much more complex backstory. Long before the modern period, Japanese monks studied and wrote about the precepts and debated what forms they should take and what roles they should play both in personal religious cultivation and in temple administration and monastic life. That history is vividly reconstructed in the present volume, a collection of groundbreaking essays by Paul Groner.

Groner focuses on the Tendai tradition because of its broad impact on medieval Japanese religion and society and, in particular, its role in setting the terms of debate over precepts and ordination. Controversy began when the Japanese Tendai founder Saich (766/767822) resolved to abandon as Hnayna the mainstream Buddhist practice of ordaining monks according to the Vinaya, or traditional monastic rules, and to ordain his disciples instead with the bodhisattva precepts set forth in the Brahms Net Sutra (Fanwang jing). Saichs decision had momentous consequences. On one hand, it freed his fledgling Tendai institution from domination by the rival schools based in the Japanese capital of Nara and also supported his vision of a unified Buddhism grounded in the one vehicle of the Mahyna. On the other hand, the bodhisattva precepts did not distinguish between lay and clerical practitioners and were thus unsuited as a guide to temple regulation or monastic training. Another issue concerned the relation of the bodhisattva precepts to the Lotus Sutra, the central scripture of the Tendai School and widely revered as kyamuni Buddhas final and highest teaching. In these essays, the fruit of more than thirty years study, Groner draws on canonical sources, x commentaries, temple rules, debate texts, oral transmission records, ritual manuals, and other sources to piece together an enthralling account of how Saichs successors wrestled with these problems over the ensuing centuries. Along a richly nuanced spectrum of interpretation, tension emerged between two poles. Some exegetes understood the precepts as innate, arising from the primordial mind or buddha nature, and downplayed their importance as rules of conduct. Interpretations of this kind often drew on the hermeneutics of esoteric Buddhism and original enlightenment (hongaku) thought, which saw liberation as direct apprehension of the perfect interpenetration of all phenomena and thus tended to collapse the Buddhist path structure into a single moments faith and understanding. Such readings viewed ordination less as an induction into the norms of a renunciate community than as an initiation rite confirming ones innate buddhahood; though doctrinally sophisticated, these readings legitimized a relaxed stance toward monastic discipline. In contrast, other interpreters affirmed the role of the precepts in governing religious life; they devised new ordination rituals and monastic regulations by creatively reinterpreting their received texts and doctrines and selectively drawing on previously discarded Vinaya elements and even the practices of rival schools. Groners analysis seamlessly integrates the institutional, social, and doctrinal implications of these divergent approaches. While focused on Japan, his study has transregional implications, showing how Japanese interpretations were shaped by study of Chinese and Korean commentaries and by the experiences of monks who had traveled to China and witnessed continental monastic practice firsthand.

One of the reviewers of this manuscript wrote: Each chapter of this volume addresses topics central to Buddhism as a lived tradition: morality; monastic discipline; the boundaries between worldly and religious norms; karmic consequences; the unavoidable tensions between Buddhist ideals of universalism and the rivalries of competing doctrinal interpretations and monastic orders.It is essential reading for anyone wishing to understand the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Buddhism in Japan, not just within the Tendai tradition. Groners study indeed goes straight to the heart of problems that engaged medieval Japanese Buddhists across the boundaries of sect and lineage. Its clear style of presentation will communicate to readersTendai afficionados and non-specialists alikethe fundamental issues at stake beneath the highly condensed and technical language of Buddhist commentary.

This volume represents a landmark for the Kuroda Institute, as our first publication of a collection of essays by a single scholar. It is thus appropriate to say something about its author. Paul Groner received his PhD in Buddhist Studies from Yale University and taught for more than thirty years at the University of Virginia. He is widely recognized as a leading authority on Tendai Buddhism. In a 1974 book review, Groners then-to-be dissertation adviser, the late Stanley Weinstein, coined the phrase neglected Tendai tradition. Despite its profound influence on the religion and culture of premodern xi Japan, Tendai Buddhism had long remained understudied, especially in the West, being relegated to the status of the womb, or historical backdrop, of the better-known Pure Land, Zen, and Nichiren traditions. But today, although many questions and unexplored areas remain, Japanese Tendai is no longer neglected in Anglophone scholarship. This advance is largely thanks to Paul Groner. His first monograph,