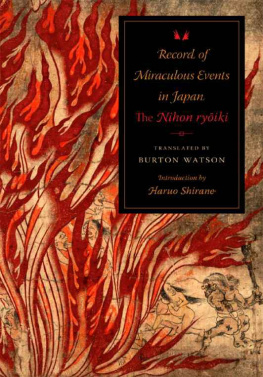

Record of Miraculous Events in Japan

TRANSLATIONS

FROM THE ASIAN CLASSICS

TRANSLATIONS FROM THE ASIAN CLASSICS

Editorial Board

Wm. Theodore de Bary, Chair

Paul Anderer

Donald Keene

George A. Saliba

Haruo Shirane

Burton Watson

Wei Shang

Record of Miraculous Events in Japan The

Nihon ryiki

TRANSLATED BY

BURTON WATSON

Introduction by

Haruo Shirane

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the Pushkin Fund toward the cost of publishing this book.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2013 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN: 978-0-231-53516-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Keikai, 8th/9th cent.

[Nihon ryoiki. English]

Record of miraculous events in Japan : the Nihon ryoiki / translated by Burton Watson ; introduction by Haruo Shirane.

pages cm. (Translations from the Asian classics)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-231-16420-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-16421-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-53516-8 (e-book)

1. Buddhist legendsJapan. 2. TalesJapan.

3. BuddhismJapanFolklore. I. Watson, Burton, 1925 translator. II. Shirane, Haruo, 1951 writer of added commentary. III. Title.

BQ 5775.J3K4413 2013

294.38dc23

2012048487

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

COVER IMAGE : Jigoku zoshi ( Scroll of the Hells , twelfth to thirteenth century), detail. (TNM Image Archives)

COVER DESIGN : Lisa Hamm

CONTENTS

Haruo Shirane

The Record of Miraculous Events in Japan ( Nihon ryiki , ca. 822), compiled in the early Heian period (7941192), is Japans first major collection of anecdotal ( setsuwa ) literature and, as such, had a huge impact on the formation of Japanese literature. It is also the first collection of Buddhist anecdotal literature, establishing a major precedent for this genre, which would come to be popular throughout the medieval period. Setsuwa (anecdotes), a modern term that literally means spoken story, are stories that were orally narrated and then written down. These recorded stories were often used for oral storytelling, resulting in new variations, which were again recorded or rewritten. The result is that setsuwa frequently exist in multiple variants, with a story usually evolving over time or serving different purposes. In being told, written down, retold, and rewritten, setsuwa presume a narrator and a listener, but not necessarily a specific author. The author of the Nihon ryiki , Keikai or Kykai (either reading is acceptable, but for the sake of consistency I follow the latter, which is the variant used in the translation that follows), was in fact more of an editor and a collector than an author in the modern sense.

Premodern setsuwa survive only in written form, sometimes (as in the Nihon ryiki ) in Chinese-style ( kanbun ) prose, providing a glimpse of the storytelling process but never reproducing it. The following example is titled On Mercilessly Skinning a Live Rabbit and Receiving an Immediate Penalty (1.16):

In Yamato province, there lived a man whose name and native village are unknown. He was by nature merciless and loved to kill living creatures. He once caught a rabbit, skinned it alive, and then turned it loose in the fields. But not long afterward, pestilent sores broke out all over his body, his whole body was covered with scabs, and they caused him unspeakable torment. In the end, he never gained any relief, but died groaning and lamenting.

Ah, how soon do such deeds receive an immediate penalty! We should consider others as we do ourselves, exercise benevolence, and never be without pity and compassion!

In a manner typical of the genre, the setsuwa is compactly written (usually no more than one or two pages), is plot and action driven, turns on an element of surprise or wonder, and is didactic (teaching karmic retribution, for the sin of killing animals, and urging compassion). In contrast to the later vernacular tales ( monogatari ), which admit to being fiction, the Nihon ryiki , like subsequent setsuwa collections, insists on the truth of the stories it includeshowever miraculous they may be.

The setsuwa-sh , or collection of setsuwa , which can be very long, was inspired in part by Chinese encyclopedias ( leishu ). In contrast to the setsuwa , which had its roots in oral storytelling, the setsuwa-sh was a literary form that provided a structured worldview (in this case, centered on karmic retribution). Often the same setsuwa appear in a number of collections. Indeed, many of the setsuwa in the Nihon ryiki reappear in later collections, including Notes on the Three Treasures ( Sanbe kotoba , 984), Biographies of Japanese Reborn in the Land of Bliss ( Nihon j gokurakuki , 985987), and Tales of Times Now Past ( Konjaku monogatari sh , ca. 1120). The setsuwa in the Nihon ryiki were probably collected and edited as a supplementary sourcebook for sermons by Buddhist priests who preached to commoner audiences that could not read kanbun . They also reflect Kykais desire to demonstrate the different ways in which the law of karmic causality is manifested.

Little is known about the author of the Nihon ryiki , except that he was a shidos (self-ordained priest), as opposed to a certified priest affiliated with a major temple and ordained by the state. At some point (probably between 787 and 795), he became affiliated as a low-ranking cleric with the Yakushi-ji temple in Nara (one of the great centers of Buddhism at the time). At the time, the central ( ritsury ) state attempted to keep a tight control on the priesthood and cracked down on private priests, who took vows without official permission. A recurrent figure in the Nihon ryiki is Gygi (Gyki, 668749), a self-ordained priest from the early Nara period, who gained a wide and popular following and was consequently prosecuted by the government before he accepted an invitation from Emperor Shmu (r. 724749) to build the large statue of the Buddha at the Tdai-ji temple in 741. The prominent position of Gygi in the Nihon ryiki indicates that he represents an ideal for Kykai, who was likewise an active private priest before eventually joining the Yakushi-ji temple. One of Kykais own accounts of himself in the Nihon ryiki states that in 787, he realized that his current poverty and secular life were the result of evil deeds he had done in a previous life, and so he decided to become an ordained priest.

Kykai edited the Nihon ryiki sometime in the early Heian period (around 822 or earlier), but the stories themselves are set in the Nara period (710784) and earlier. In Kykais time, during the reigns of Emperor Kanmu (r. 781796) and his son Emperor Saga (r. 809823), the country was rocked by considerable social disorder, famine, and plagues. It was a particularly hard time for farmers, many of whom fled from their home villages. Some of these refugees were absorbed into local temples and private estates, and others became private priests like Kykai. Unlike the officially ordained clergy in the major temples in the capital, who were of aristocratic origins, these self-ordained priests attracted a more plebian following, and many of the stories in the Nihon ryiki are about poor commoners and farmers. The Nihon ryiki deals at times with high-ranking aristocrats such as Prince Shtoku, but most of the stories concern commoners on a much lower level of society. Kykai sought to teach Buddhist principles to society as a whole. In this regard, the Nihon ryiki differs significantly from the elite literature being produced at this time, such as Nostalgic Recollections of Literature ( Kaifs , 751) and Collection of Literary Masterpieces ( Bunka shreish , 818), two noted collections of Chinese poetry and refined Chinese prose written by aristocrats. Instead, the Nihon ryiki is written in a rough, unorthodox style of Chinese-style prose that gives us a glimpse of the underside of society and the reality of everyday commoner life.