The Analects of Confucius

TRANSLATIONS FROM THE ASIAN CLASSICS

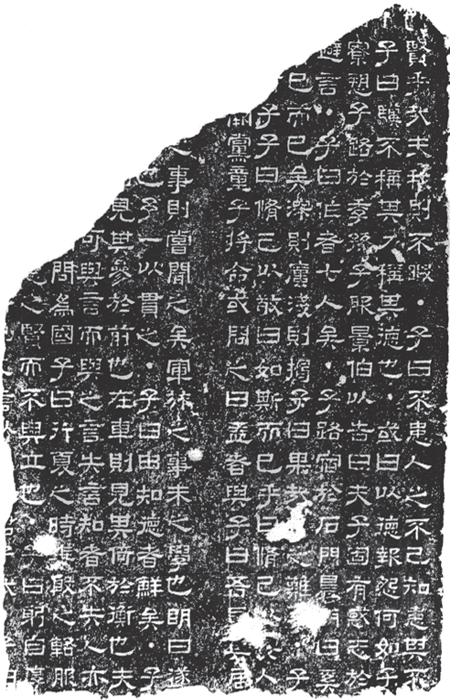

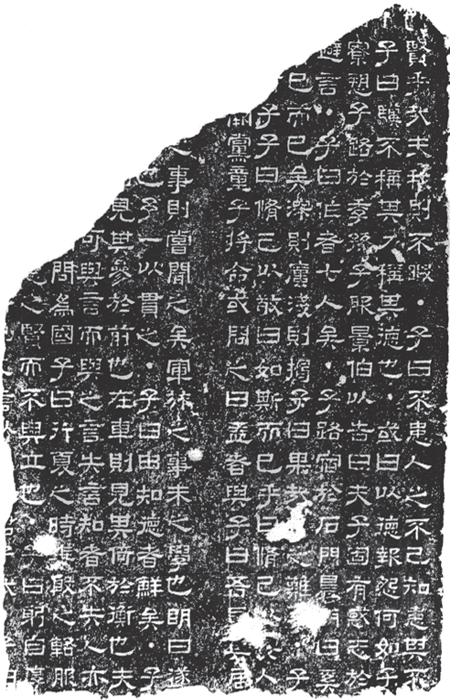

Analects of Confucius, stone stele fragment. Imperial scholars, using a special style of calligraphy called li, inscribed the Analects and other classical texts on stone stele, which they erected in the Imperial Academy in A.D. 175. The stones were destroyed soon after during the wars that brought the dynasty to an end, and the fragments were buried for protection. They were later unearthed during the Song dynasty. This fragment depicts a section of the Analects and measures 52 by 35 centimeters.

PHOTOGRAPH AND PERMISSION COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CHINA, BEIJING.

The Analects of Confucius

TRANSLATED BY BURTON WATSON

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2007 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-51199-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Confucius.

[Lun y. English]

The Analects of Confucius / translated by Burton Watson.

p. cm.(Translations from the Asian classics)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-231-14164-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-14165-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-51199-5 (electronic)

I. Watson, Burton, 1925 II. Title. III. Series.

PL2478.L3 2007

181.112DC22

2007005401

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Contents

GLOSSARY OF PERSONS

AND PLACES

Lunyu, or The Analects of Confucius, has probably exercised a greater influence on the history and culture of the Chinese people than any other work in the Chinese language. Not only has it shaped the thought and customs of China over many centuries, but it has played a key role in the development of other countries that were within the Chinese cultural sphere, such as Korea, Japan, and, later, Vietnam.

Readers encountering the text for the first time might wonder how this rather brief collection of aphorisms and historical anecdotes could have been so influential. The text, probably compiled in stages some time during the fourth century B.C.E., was at first only one of many philosophical works that embodied the teachings of this or that school of early Chinese thought. The followers of the teachings of Confucius were referred to collectively as the Ru school, which denotes persons who devote themselves to learning and the peaceful arts (as opposed to martial matters).

Some centuries later, when Emperor Wu (r. 14187 B.C.E.) of the Han dynasty declared Confucianism the official doctrine of the state, the Analects and other texts associated with Confucius assumed enormous importance. They were regarded as repositories of knowledge of how the empire had been governed in the model eras of antiquity and how the Chinese government system, and society as a whole, should be ordered. In still later centuries, the Analects was treated as a beginning text in the study of classical Chinese, to be committed to memory and, when students were more advanced, studied exhaustively and with its lessons examined in depth.

CONFUCIUS

According to tradition, Confucius was born in 551 B.C.E. His family name was Kong; his personal name, Qiu; and his polite name (the name by which most persons would have addressed him), Zhongni. The name Confucius is a Latinized form of Kong fuzi, or Respected Master Kong, a title commonly used to refer to him in Chinese.

Confucius was born in the small feudal state of Lu, situated in northeastern China in the area of present-day Shandong Province. His father, who was a member of the shi class, the lowest rank of the nobility, died when Confucius was very young. It is clear from the Analects that Confucius grew up in considerable poverty, an experience that seems to have made him particularly sensitive to matters of wealth and class. At an early age, as he tells us, he devoted himself to learning, and the importance of education is a major theme in the Analects.

The extent to which this learning related to written texts and to which it was based on oral traditions is unclear. The Analects refers frequently to two texts, the Book of Odes and the Book of Documents, both of which Confucius, according to legend, had some hand in editing. A third early text, the Book of Changes, is mentioned in one version of the Analects. These constitute three of what later became known as the five Confucian Classics, the other two being the Spring and Autumn Annals, a chronicle of the state of Lu said to have been edited by Confucius, and the Book of Rites, a collection of texts on ritual.

Whether Confuciuss learning derived from written texts or from oral traditions, he appears to have been intensely concerned with those that reflected the early culture of China, particularly that of the sage rulers Yao and Shun of high antiquity and of the early rulers of the Xia, Yin, and Zhou, the so-called Three Dynasties, when China was believed to have enjoyed exemplary eras of peace and social order. He was especially interested, it would seem, in the rites, music, and other cultural elements that distinguished these periods.

Confuciuss ambition, it would appear, was to gain official position in his native state of Lu so that he could put his ideals on morality and good government into practice. Later legend depicts him as, in fact, holding fairly high public office in Lu, but there is little or no evidence in the Analects to support such a supposition. To understand the problems that Confucius faced in his search for office, we must review the social and political situation in the China of his time.

The Zhou people, founders of the dynasty under which Confucius lived, came originally from a region in western China. Kings Wen and Wu, who founded the dynasty, probably around 1040 B.C.E., had their capital in the area of present-day Xian. Under their rule and that of their immediate successors, China was divided into a vast number of feudal domains whose leaders acknowledged fealty to the Zhou king (or Son of Heaven) and aided him in repelling the attacks of non-Chinese peoples living on Chinas borders. One such attack in 771 B.C.E., however, forced the Zhou rulers to abandon their original capital in the west and move east to the area of Luoyang, a step that marked the beginning of the era known as Eastern Zhou (771256 B.C.E.).

By this time, the Zhou kings had ceased to wield any real authority but were allowed to continue occupying the throne because of their religious significance as heads of the ruling clan. Actual power had meanwhile passed into the hands of the rulers of the larger feudal states, such as Qi on the Shandong Peninsula and Jin in northeastern China. In the Analects, Confucius is depicted as speaking favorably of the leaders of these two states because of their ability, at least for a time, to restore order and unity to the nation and protect it from foreign invasion.

Because the Zhou kings were no longer strong enough to enforce conditions of order and stability, as they supposedly had in earlier centuries, the more powerful feudal states were able to swallow up their weaker neighbors and ally themselves with one another to advance their aims. Thus the era was marked by almost constant warfare, the feudal lords, who lived in walled cities, venturing forth in cumbersome war chariots to attack this or that foe, accompanied by foot soldiers enlisted from the peasantry, who ran alongside the chariots. Confucius himself disclaimed any knowledge of military matters and deplored the warlike tenor of the age, but it is reflected in numerous passages of the

Next page