Translation, introduction, and annotation copyright 2015 by David Hinton All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication is available. ISBN 978-1-61902-556-1

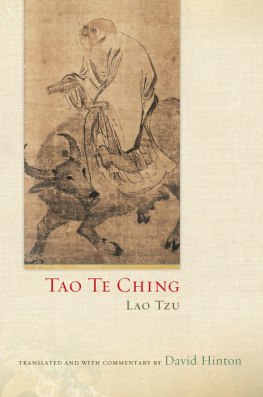

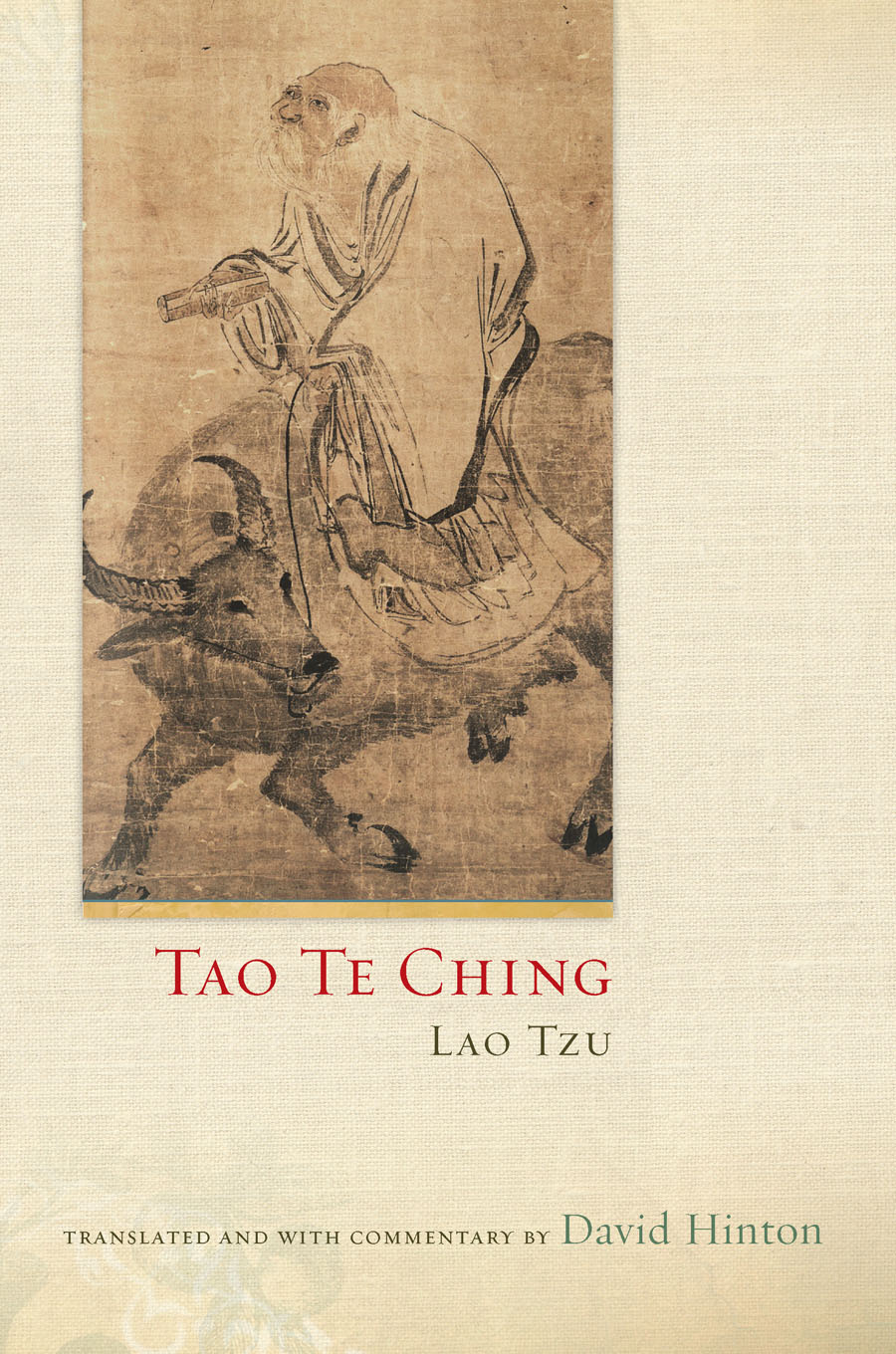

Chang Lu (ca. 1490-1563).

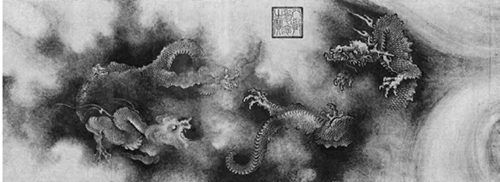

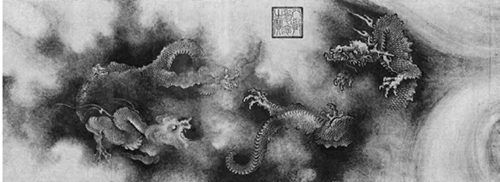

Chen Jung (active first half of the 13th century).

Chen Jung (active first half of the 13th century).

Courtesy of The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Cover design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Interior design by David Bullen COUNTERPOINT 2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318 Berkeley, CA 94710 www.counterpointpress.com Printed in the United States of America Distributed by Publishers Group West 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 e-book ISBN 978-1-61902-684-1 ILLUSTRATIONS CoverLao Tzu Riding an Ox. Chang Lu (ca. 14901563). Courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China Image of Lao Tzu traveling out of China into the West. 29-30. InteriorNine Dragons (detail). InteriorNine Dragons (detail).

Chen Jung (active first half of the 13th century). Courtesy of The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Image of ancient dragon (on the left) instructing a young dragon (on the right). See Introduction p. 15-16. TAO TE CHING Lao Tzu

Introduction I n the realm of ancient Chinese myth, earths generative natural process takes the awesome form of dragon.

Both feared and revered as the mysterious force of life itself, dragon animates all things in the unending cycle of life and death and rebirth. As it embodies the process of change itself, dragon appears only to disappear again, and so is in constant transformation. Its scales glisten in the bark of rain-swept pines, and it roams seething waters. It descends into deep pools and lakes in autumn, where it hibernates until spring, when its awakening is the awakening of spring and the return of life to earth. It rises from the depths and ascends into the sky, its voice filling the spring winds that scatter autumn leaves. It takes the shape of storm clouds, its claws becoming lightning, and produces the life-bringing spring rains.

Throughout the millennial turning of this seasonal process, spirituality in ancient China was primarily a matter of dwelling at the deepest levels of our belonging to dragons realm. And this spiritual ecology traces its source back to the origins of Taoist thought: to the sage antics of Chuang Tzu and beyond, to the dark ambiguities and evocative silences of Lao Tzus mysterious poetry. Indeed, after his legendary encounter with Lao Tzu, an awestruck Confucius exclaimed: A dragon mounting wind and cloud to soar through the heavens such things are beyond me. And today, meeting Lao Tzu, it was like facing a dragon. The question of the historical Lao Tzu is itself a case study in dragons protean nature. Centuries before the first scraps of Lao Tzus legend coalesced, he had already vanished into the scattered fragments that eventually evolved into the little book that now bears his name.

In the cultural legend, Lao Tzu was an elder contemporary of Confucius (551479 B.C.E. ). But in spite of his stature as a sage, nothing verifiable is known about him, and even the cultural legend is made up of very few facts: he was born in the state of Chu and became a court archivist in the Chou capital; he was consulted by Confucius, who emerged from the meeting awestruck; he left the world, heartsick at the ways of people, and as he was going through a mountain pass to vanish into the far west, the gatekeeper there convinced him to leave behind his five-thousand-word scroll of wisdom. The actual biography of the Tao Te Chings author, whose name simply means Old Master, no doubt looks quite different. He was probably constructed out of fragments gleaned from various old sagemasters active between perhaps the sixth and fourth centuries B.C.E. , at the historical beginnings of Chinese philosophy.

These early texts were worn away, broken up, scattered, assembled, and reassembled: a geologic process lasting several hundred years that apparently included a number of sage editors who wove this material into the single enduring voice that we find in the Tao Te Ching. The result of this rather impersonal process was a remarkably personal presence: if we look past the fragmentary text and oracular tone, we find a voice that is consistent and compassionate, unique and rich with the complexities of personality. It seems likely that a good deal of the material woven into Lao Tzus voice actually predates the historical beginnings of Chinese philosophy, deriving from an ancient oral tradition. The sayings themselves may predate Lao Tzu by three centuries, but the origins of this oral tradition must go back to the cultures most primal roots, to a level early enough that a distinctively Chinese culture had yet to emerge, for the philosophy of Tao embodies a cosmology rooted in that most primal and wondrous presence: earths mysterious generative force. This force must have been truly wondrous to those primal people not only because of the unending miracle of new life seemingly appearing from nothing, but also because that miracle was so vital to their well-being, providing them with food, water, clothing, shelter, and of course, a future in their children. In the Paleolithic, the human experience of the mystery of this generative force gave rise to such early forms of human art as vulvas etched into stone and female figures emphasizing the sense of fecundity. This art was no doubt associated with the development of humankinds earliest spiritual practices: the various forms of obeisance to a Great Mother who continuously gives birth to all creation, and who, like the natural process which she represents, also takes life and regenerates it in an unending cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

These phenomena appear to be ubiquitous among later Paleolithic and early Neolithic cultures, where they are integral to gynocentric and egalitarian social structures. In the Tao Te Ching, this venerable generative force appears most explicitly in Lao Tzus recurring references to the female principle (see Key Terms: mu, etc.), such as: mother of all beneath heaven, nurturing mother, valley spirit, dark female-enigma. But its dark mystery is everywhere in the Tao Te Ching, for it is nothing other than Tao itself, the central concept in Lao Tzus thought. It is a joy to imagine that the earliest of the sages woven into Lao Tzu, those responsible for the core regions of his thought, were in fact women from the cultures proto-Chinese Paleolithic roots. The primal generative process revered by those earliest of Chinese sages takes on new dimensions in Lao Tzus Tao, dimensions that carry it into realms we now speak of as ontology and ecology, cosmology, phenomenology, and social philosophy. Tao originally meant way, as in pathway or roadway, and Lao Tzu recast it as a spiritual Way by using it to describe that inexplicable generative force seen as an ongoing process (hence a Way).

Translation, introduction, and annotation copyright 2015 by David Hinton All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication is available. ISBN 978-1-61902-556-1 Lao Tzu Riding an Ox. Chang Lu (ca. 1490-1563). Nine Dragons. Chen Jung (active first half of the 13th century). Nine Dragons. Chen Jung (active first half of the 13th century).

Translation, introduction, and annotation copyright 2015 by David Hinton All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication is available. ISBN 978-1-61902-556-1 Lao Tzu Riding an Ox. Chang Lu (ca. 1490-1563). Nine Dragons. Chen Jung (active first half of the 13th century). Nine Dragons. Chen Jung (active first half of the 13th century).