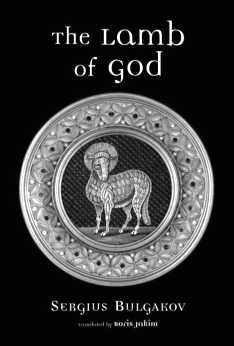

"In his new translation of Bulgakov's Lamb of God Boris Jakim makes available to the English-language reader one of the most controversial works of Orthodox Christian theology ever written; he also makes a vital contribution to the creation of an Orthodox theological idiom in English. For both reasons this book will remain an irreplaceable resource for new work in theology."

- ROBERT BIRD

University of Chicago

THE LAMB OF GOD

Sergius Bulgakov

Translated by Boris jakim

Contents

vii

viii

xiii

Translator's Acknowledgment

I wish to express my heartfelt gratitude to my dear friend William B. Eerdmans Jr., the director of Eerdmans Publishers. It was his idea to publish a series of books of Russian theology in translation ("the Russian front," he calls it), and without his enthusiasm Bulgakov's great trilogy (completed with this volume) would never have achieved its English-language incarnation.

Translators Introduction

I

This idea also signifies that all human beings participate, at least potentially, in the Divine-Humanity; that, individually, we are god-men, and that, collectively, we are the divinehumankind.

2

Father Sergius Bulgakov (1871-1944) was the twentieth century's most profound Orthodox systematic theologian. Born into the family of a poor provincial priest, Bulgakov had a strict religious upbringing and entered the seminary at a young age. But owing to a spiritual crisis in the direction of materialism and atheism, he did not complete his seminary studies. He chose instead to follow a secular course of study, which led to his matriculation at the University of Moscow, where he specialized in political economics.

This marked the beginning of his relatively short-lived Marxist period. In 1901, after which he defended his master's thesis, "Capitalism and Agriculture" (1900), he was appointed professor of political economy at the Polytechnical Institute of Kiev. During his years there (1901-6), he underwent a second spiritual crisis, this time in the direction of idealist philosophy and the religion of his youth.

Influenced first by the philosophies of Kant and Vladimir Solovyov, and then by the great Orthodox theologian Pavel Florensky, Bulgakov gradually began to articulate his own original sophiological conception of philosophy. This conception was first elaborated in his Philosophy of Economy, for which he received his doctorate from the University of Moscow in 1912. Later, in The Unfading Light (1917), he gave his sophiological ideas definite philosophical shape. Following this, Bulgakov's intellectual output was, for the most part, theological in character. Indeed, his personal religious consciousness flowered in the following year, and he accepted the call to the priesthood, receiving ordination in 1918.

These years of internal crisis and growth in Bulgakov's personal life paralleled the tumultuous period in Russian political and social life that climaxed in the October Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent Bolshevik ascendancy. In 1918 Bulgakov left Moscow for the Crimea to assume a professorship at the University of Simferopol. But his tenure was short-lived, owing to Lenin's banishment in 1922 of more than 10o scholars and writers deemed incurably out of step with the official ideology.

Bulgakov left the Soviet Union on January 1, 1923, alighting first in Constantinople and then in Prague. Finally, having accepted Metropolitan Eulogius's invitation both to become the dean of the newly established Saint Sergius Theological Institute and to occupy the chair of dogmatic theology, he settled in Paris in 1925. Here, until his death in 1944, he would make his most fruitful and lasting contributions to Orthodox thought.

3

But this passage concludes with testimony about the heavenly glorification of Christ (Phil. 2:9-Jo): kenosis leads to glory.

I have eliminated or shortened some of Bulgakov's notes, which tend to be over-detailed and sometimes arcane. Throughout the text Bulgakov refers to a number of his own works; I give the full bibliographic citation only the first time the work is mentioned. I have used the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible, since I consider it to be the English-language version that most closely approaches the beauty of the Russian Bible. I have sometimes modified the KJV to make it conform with the Russian Bible.

Here and there, in untwisting some difficult passages, I have relied on the excellent translation into French by Constatin Andronikof: Du Verbe incarne: L'Agneau de Dieu, 2nd ed. (Lausanne: Editions L'Age d'Homme, 1982).

Authors Preface

And the Spirit and the bride say, Come. And let him that heareth say, Come.

Rev. 22:17

What can I say about the theme, aspiration, and heart of this book? What can I say about Christ's Divine-Humanity and about our divine-humanity? The salvation effected by Christ is accomplished in the individual soul, which is more precious than the world. And the path of the individual soul consists in the feat of the struggle against sin, against the tragic rupture in the soul of fallen man. Its path consists in subjugating the flesh to the spirit and in taking up Christ's cross. This indisputable truth abides at the center of Christian life, and we are clearly conscious of it.

But far from sufficiently understood is another aspect of the truth about salvation: salvation is not only personal and individual but also universal and omni-ecclesial. This is the truth about the reign of Christ in the world. The revolt of the kings and people of the earth against their Lord and Christ began long ago. In essence, this revolt dates from the very beginning of the Church; it did not immediately flare up into an open revolution, however, but by clever and sinuous wiles it tried to diminish, limit, usurp, and make impotent the coming of God in the flesh. This revolt tried to abolish the Divine-Humanity. Its aim was to enable the prince of this world to keep the world in his hands. Docetism and gnosticism, manicheanism and transcendentism, Hinduism and Jesuitism, and so on, a great multitude of conscious and half-conscious opponents of the Divine-Humanity - in the name of gnosis, piety, asceticism, moralism, spiritualism - have sought and still seek to abolish the power of the Divine-Humanity, to disincarnate the Logos. We can add to this the envious, theomachic, Antichrist-like divinization of man, which seeks to supplant the Divine-Humanity: the man-god seeks to supplant the GodMan. And this varied army of enemies that serves the Antichrist has succeeded in confounding and frightening humanity, in convincing it that Christ has abandoned the world and that His Kingdom, which is not of this world, will never be realized in this world. Compelled to adapt ourselves to this fact, our only recourse appears to be to diminish our goals, to accept signs as accomplishments, to resign ourselves to half-measures and incongruities, or simply to flee - in fact or in spirit, ascetically or theologically - from this world into the desert of nihilism, of indifference, and of contempt; for the world exists only to be rejected ascetically, to be relegated to fire.