The

SCIENTIFIC

REVOLUTION

science culture

A series edited by Steven Shapin

The

SCIENTIFIC

REVOLUTION

STEVEN SHAPIN

the university of chicago press

chicago and london

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1996 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 1996

Paperback edition 1998

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN: 0-226-75020-5 (cloth)

ISBN: 0-226-75021-3 (paper)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shapin, Steven.

The Scientific Revolution / Steven Shapin

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-226-75020-5 (cloth : alk.paper).

ISBN 0-226-75021-3 (pbk : alk.paper)

1. Science History. I. Title.

Q125.S5166 1996

509dc20 96-13196

CIP

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

For Abigail

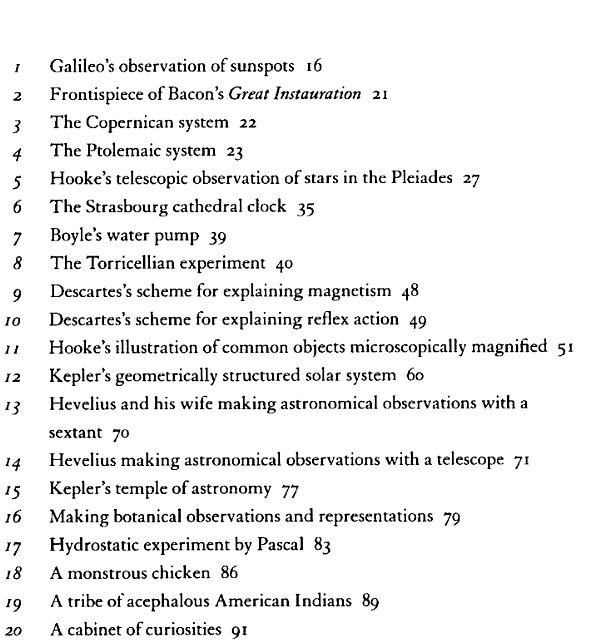

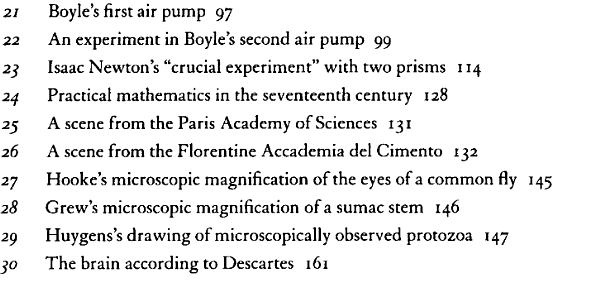

Photo Credits

I thank the following institutions for permission to publish the illustrations reproduced here: the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley (figs, 1 and 20); the National Museum of American History, Washington, D.C. (fig. 6); the Syndics of Cambridge University Library (figs. 13, 14, 17, 23, and 25); the Burndy Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts (fig. 15); and Edinburgh University Library (figs. 21 and 22).

Acknowledgments

This is a work of critical synthesis, not one of original scholarship. Although its aim is to give an up-to-date interpretation of the Scientific Revolution, taking account of much historical research produced in the past ten or fifteen years, it nevertheless draws on the research of generations of scholars. Accordingly, the greatest debts I wish to acknowledge are to the many other historians whose work I use so freely, and whose books and papers are listed in the accompanying bibliographic essay. There should be no doubt about the legitimate sense in which this is as much their book as mine, yet I must also acknowledge that the interpretations I put on their work, and the way I organize their disparate findings and claims, reflect my own particular point of view. For this, of course, I accept entire responsibility.

To enable this book to address a general readership most effectively, and to make the exposition flow as smoothly as possible, I chosewith some concern about setting aside conventions traditionally observed in works by specialist scholars written for other specialistsnot to burden the text with dense citations of relevant secondary literature. Moreover, direct quotations from modern historians were reserved for just a few occasions when I judged that their particular ways of putting things were uniquely effective or revealing, or when their precise formulations had attained something like "proprietary" status.

Since my aim was to write a short text that might be useful for teaching, I have, over many years, tried out various versions of this book's accounts and arguments with my students, especially those at Edinburgh University when, during the 1970s and 1980s, I taught the history of science. Whether explicitly or implicitly, these are the people who told me most effectively whether I was making myself understood and, indeed, whether I was making sense. I thank them all.

I am also fortunate in having a few academic colleagues and friends who repeatedly told me that such a book might be useful, who encouraged me through some particularly troublesome passages in its career, and who read earlier versions, making valuable suggestions about many aspects of its content, organization, and presentation. In this connection it is a pleasure to acknowledge the special contributions of Peter Dear and Simon Schaffer. No one familiar with their work could possibly associate them with this book's remaining faults. Two anonymous readers for the University of Chicago Press wrote constructive and detailed reports far beyond the usual call of duty. For assistance in locating several of the illustrations, I am grateful to Paula Findlen, Karl Hufbauer, Christine Ruggere, Simon Schaffer, and Deborah Warner. I thank Alice Bennett, senior manuscript editor at the University of Chicago Press, whose diligent and dedicated copyediting did much to make my writing clearer and less fussy. My editor, Susan Abrams, has throughout given the support and advice for which she has become so well known and so highly respected.

Introduction

The Scientific Revolution: The History of a Term

There was no such thing as the Scientific Revolution, and this is a book about it. Some time ago, when the academic world offered more certainty and more comforts, historians announced the real existence of a coherent, cataclysmic, and climactic event that fundamentally and irrevocably changed what people knew about the natural world and how they secured proper knowledge of that world. It was the moment at which the world was made modern, it was a Good Thing, and it happened sometime during the period from the late sixteenth to the early eighteenth century. In 1943 the French historian Alexandre Koyr celebrated the conceptual changes at the heart of the Scientific Revolution as "the most profound revolution achieved or suffered by the human mind" since Greek antiquity. It was a revolution so profound that human culture "for centuries did not grasp its bearing or meaning; which, even now, is often misvalued and misunderstood." A few years later the English historian Herbert Butterfield famously judged that the Scientific Revolution "outshines everything since the rise of Christianity and reduces the Renaissance and Reformation to the rank of mere episodes.... [It is] the real origin both of the modern world and of the modern mentality." It was, moreover, construed as a conceptual revolution, a fundamental reordering of our ways of thinking about the natural. In this respect, a story about the Scientific Revolution might be adequately told through an account of radical changes in the fundamental categories of thought. To Butterfield, the mental changes making up the Scientific Revolution were equivalent to "putting on a new pair of spectacles." And to A. Rupert Hall it was nothing less than "an a priori redefinition of the objects of philosophical and scientific inquiry."

This conception of the Scientific Revolution is now encrusted with tradition. Few historical episodes present themselves as more substantial or more self-evidently worthy of study. There is an established place for accounts of the Scientific Revolution in the Western liberal curriculum, and this book is an attempt to fill that space economically and to invite further curiosity about the making of early modern science.1 Nevertheless, like many twentieth-century "traditions," that contained in the notion of the Scientific Revolution is not nearly as old as we might think. The phrase "the Scientific Revolution" was not in common use before Alexandre Koyr gave it wider currency in 1939. And it was not until 1954 that two bookswritten from opposite ends of the historiographic spectrumused it as a main title: A. Rupert Hall's Koyr-influenced The Scientific

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.