Foreword

Only five years old, my younger son, Henry, answered the telephone and passed the cordless on to my wife. She called me down from my study, and the caller, a good friend who lives near the church I serve as priest, told me the news. She described what her son had seen: an area cordoned off by yellow tape, a person lying on the ground between the two main buildings, the church proper and the old rectory.

The two-mile stretch between my house on a college campus and the churchfarmland, woods, and gracious homeswas lit by the autumn twilight in the Hudson River Valley, filling the air with colors and a still vibrancy unlike any other time of year. The tangible beauty of light seeming to hang in the air put me in a mood to wish away my gathering sense of dread. I had few defenses at my disposal for how cruel that evening would prove, how far its pain would reach.

A young woman lay fallen between the buildings. Her throat had been cut; the officer on the scene believed she was dead. To give the woman last rites, I went into the church to collect my stole and my vessel of oil. Then, outside again and kneeling next to the woman, I recognized hera student whom I had met to counsel from time to time, named Anna.

Annas eyes, still open and clear with apparent life, picked up the last rays of the sun. I anointed her forehead and prayed for her. The wound across her throat was dreadful. An autopsy later found that the knife-blow that killed her had chipped her spine. When my prayers had ended, I asked a newly arrived officer, apparently senior to the first, to cover Annas body and face. He agreed without hesitation.

Recollection of an ancient text, not part of the last rites, stirred just out of reach of conscious recognition as I stood up. The memory had been awakened by the rays of the setting sun in Annas eyes, yet resisted identifying itself. I was not surprised, or even frustrated, by the elusive memory; my mental processes had slowed to the speed of a waking dream. Tenants who rented rooms in the old rectory emerged from the house. Earlier that evening they had heard screams, one of them ran downstairs to find Anna wounded, and another had telephoned the police. Now they all stood outside, paralyzed by a scene none of us could understand. We prayed for Anna together until the gathering chill of the evening sent the tenants back into their homes.

I agreed to meet with them later in the old rectory. Most of that night saw me either talking with that small group, or in the church with students from the college, who were drawn in clusters to the site by news of Annas murder. But before I attempted to counsel others, I excused myself to return my stole and vessel of oil to the sacristy of the church, to call my wife to let her know what had happened, and to take a moments solitude. Walking west toward the side door of the church, I saw the last of the suns colors disappear over the mountains across the Hudson River. Then the text that had stirred in my memory crystallized in my mind.

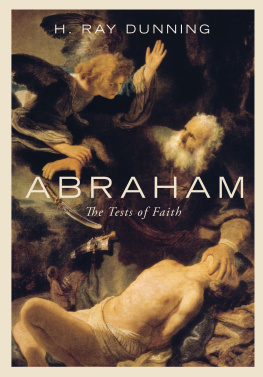

The memory related to the classic passage from Genesis where God tells Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac. Abraham dutifully climbs Mount Moriah, binds his son with rope as he would a sacrificial lamb, and is about to slit Isaacs throat when an angel intervenes. This is the story of how a human being was bound (aqedah) in order to be sacrificed.

Different versions of Genesis 22 circulated in an immensely varied tradition called the Aqedah or Binding of Isaac in Rabbinic sources, andwith key changesin both Christian and Islamic texts. Several ancient interpreters stated, or implied, that Abraham did cut his sons throat, and that Isaac had bled out and was offered in the sacrificial fire.

In texts I had studied in England twenty years before Annas murder, as Abraham positioned the knife at his sons neck, Isaac looked up to heaven and saw angels there. Abrahams nearest approach to heaven was indirect, through what was reflected in Isaacs eyes; the offered son saw Gods presence and Gods will in a way the sacrificing father could not. The angel that stayed Abrahams knife was Isaacs vision, which his father saw only by reflection. Annas throat and Annas eyes had brought to life an image whose visceral power came home to me in that moments silence in the sacristy as never before.

The events involved in Annas murder in 1998 and its aftermath were complex, but the dreadful simplicity of the act, the slaughter of a young woman with a hunting knife, matches the simplicity of her killers testimony during his successful insanity defense. A voice, he said, had ordered the murder, and his use of drugs had made him compliant. A festival a week before the crime had celebrated the Afro-Caribbean god Ogun, whose knife is believed to liberate vital forces from the victims he sacrifices. The cult of Ogun represents the same impulse with which the Aqedah struggles. A primordial compulsion had visited the doorstep of our church, as it has visited countless doorsteps before and since, taking the life of an innocent victim.

The laws of New York State provide for the psychiatric treatment of a murderer rather than his imprisonment, if the killer is not responsible for the killing. A quasi-religious motivation for the crime plays into the argument for treating a killer as a patient. In the judgment of the court, an impulse like Abrahams had motivated Annas killer to do his crime.

Three years after Annas death, I was in my church on another tragic day, but with a larger congregation. The attacks of September 11, 2001, took lives, broke up families and businesses, and robbed millions of people of the sense of security they had once enjoyed. Those who gathered that evening in the church, some of them remaining in meditative prayer long after the service ended, had either suffered losses directly or were drawn in sympathy to those who had suffered. They struggled to understand the motives of the hijackers, and of suicide bombers in the Middle East and elsewhere, who were proclaiming themselves martyrs.

In the weeks that followed we learned of the letter of guidance found in Mohamed Attas bags, left behind in Boston on the day of the attacks. The letter gave instructions for ritually purifying ones body, reciting the Quran before boarding the plane, and remembering, You must make your knife sharp and must not discomfort your animal during the slaughter. Following a pattern discernible within the Quran, in a story directly comparable to the Aqedah of Genesis 22, the Atta letter makes the sacrifice of Ibrahim (the Arabic equivalent of Abraham) and the willingness of his son to be offered into a model of true martyrdom.

Islam is by no means unique in using the Aqedah as a model for martyrs and as a justification for violence. As Judaism has praised the sacrifice of Abraham, and Islam the offering of Ibrahim, Christianity since the first century has contended that Jesus accomplished in actions the offering that Isaac only symbolized. The key Christian belief in Jesus as the sacrificial Lamb of God reinterprets and recasts the image of Isaac in Genesis.

Fundamentalist Christians have been particularly invested in this theology, and one of their number unleashed domestic terrorism in the United States well before Mohamed Attas attack. Timothy McVeigh, a former soldier in the American army who belonged to the militant Christian Identity movement, bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995. One hundred sixty-eight Americans died and more than five hundred were wounded by McVeighs truck bomb. When asked about the children in a day care facility whose lives he had ended that day, McVeigh allowed that there had been collateral damage. He welcomed his own execution on June 11, 2001, at the federal penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana, by a lethal injection.