Past Masters

Muhammad

Michael Cook is a professor of Near Eastern studies at Princeton University and the author of several books on the history of the Middle East.

Postscript to 1996 reissue: Since 1977, the total number of Muslims has increased to just over a billion. They remain a little over a sixth of the world's population, while Christians amount to about a third. The number of Marxists, by contrast, is no longer significant, and probably never was; events since I wrote have fully home out the scepticism expressed on this point by Mr Gulam Hyder of Peshawar in a letter he wrote tome in 1987.

Past Masters

AQUINAS Anthony Kenny

ARISTOTLE Jonathan Barnes

AUGUSTINE Henry Chadwick

BENTHAM John Dinwiddy

THE BUDDHA Michael Carrithers

CLAUSEWITZ Michael Howard

COLERIDGE Richard Holmes

DARWIN Jonathan Howard

DESCARTES Tom Sorell

DISRAELI John Vincent

DURKHEIM Frank Parkin

GEORGE ELIOT Rosemary Ashton

ENGELS Terrell Carver

ERASMUS James McConica

FREUD Anthony Storr

GALILEO Stillman Drake

GOETHE T. J. Reed

HEGEL- Peter Singer

HOBBES Richard Tuck

HOMER Jasper Griffin

HUME A. J. Ayer

JESUS Humphrey Carpenter

JOHNSON Pat Rogers

JUNG Anthony Stevens

KANT Roger Scrutmi

KEYNES Robert Skidelsky

KIERKEGAARD Patrick Gardiner

LEIBNIZ G. MacDonald Ross

LOCKE John Dunn

MACHIAVELLI Quentin Skinner

MALTHUS Donald Winch

MARX Peter Singer

MONTAIGNE Peter Burke

MONTESQUIEU Judith N. Shklar

THOMAS MORE Anthony Kenny

MUHAMMAD Michael Cook

NEWMAN Owen Chadwick

NIETZSCHE Michael Tanner

PAINE Mark Philp

PAUL E. P. Sanders

PLATO R. M. Hare

ROUSSEAU Robert Wokler

RUSSELL A. C. Grayling

SCHILLER T. J. Reed

SCHOPENHAUER Christopher Janaway

SHAKESPEARE Germaine Greer

ADAM SMITH D. D. Raphael

SPINOZA Roger Scruton

TOCQUEVILLE Larry Siedentop

vico Peter Burke

VIRGIL Jasper Griffin

WITTGENSTEIN A. C. Grayling

Forthcoming

JOSEPH BUTLER R. G. Frey

COPERNICUS Owen Gingerich

GANDHI Bhikhu Parekh

HEIDEGGER Michael Inwood

SOCRATES C. C. W. Taylor

WEBER PeterGho6h and others

Michael Cook

Muhammad

Preface

It is unlikely that Muhammad would have warmed to the series in which this book appears, or cared to be included in it. Its very title smacks of polytheism; the term `master' is properly applicable only to God. He might also have resented the insinuation of intellectual originality. As a messenger of God, his task was to deliver a message, not to pursue his own fancies.

My own reservations about writing this book arise from different grounds. Muhammad made too great an impact on posterity for it to be an easy matter to place him in his original context. This is both a question of historical perspective and, as will appear, a question of sources. The result is that the only aspect of the book about which I feel no qualms is the brevity imposed by the format of the series. The attempt to write about Muhammad within such a compass has brought me to confront issues I might not otherwise have faced, and in ways which might not otherwise have occurred to me.

I give frequent references to the Koran (K), and occasional references to the Sira of Ibn Ishaq (S); for details, see below, p. 91. For simplicity I have transcribed Arabic names and terms without diacritics; note that the `s' and `h' in the name `Ibn Ishaq' are to be pronounced separately (more as in `mishap' than in `ship').

My thanks are due to Patricia Crone, Etan Kohlberg, Frank Stewart, Keith Thomas and Henry Hardy for their comments on a draft of this book; and to Fritz Zimmermann for a critical reading of what might otherwise have been the final version, and for a substantive influence on my understanding of Muslim theology.

Contents

Introduction

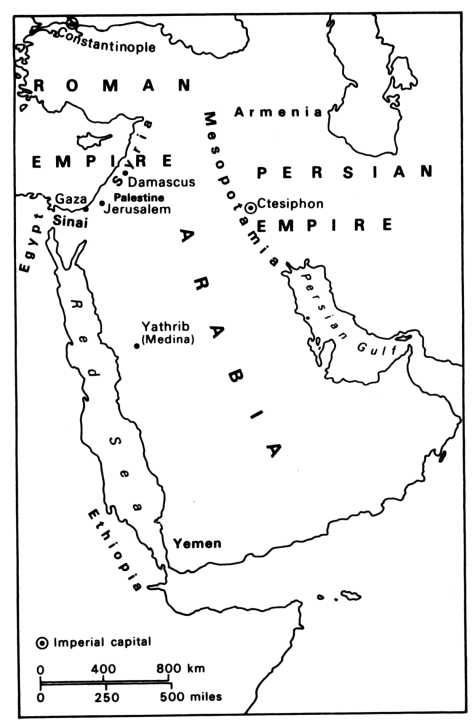

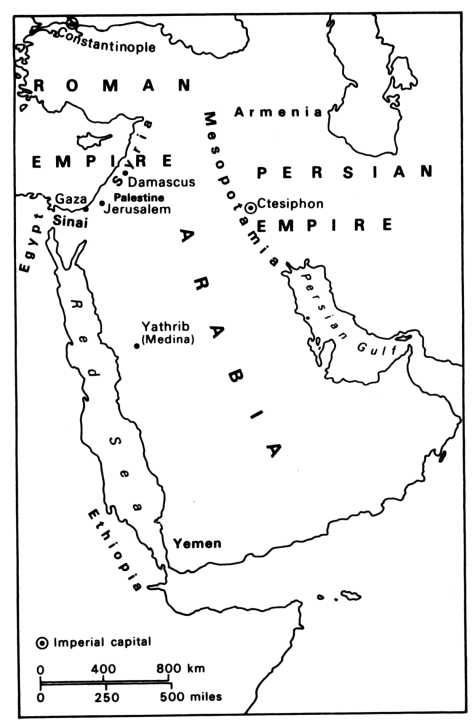

The Muslim world extends continuously from Senegal to Pakistan, and discontinuously eastwards to the Philippines. In 1977 there were some 720 million Muslims, just over a sixth of the world's population. The proportion might have been a great deal higher if the Muslims of Spain had applied themselves more energetically to the conquest of Europe in the eighth century, if the sudden death of Timur in 1405 had not averted a Muslim invasion of China, or if Muslims had played a more prominent role in the modern settlement of the New World and the Antipodes. But they have remained the major religious group in the heart of the Old World. In terms of sheer numbers they are outdone by the Christians, and arguably also by the Marxists. On the other hand, they are considerably less affected by sectarian divisions than either of these rivals: the overwhelming majority of Muslims belong to the Sunni mainstream of Islam.

There are many Muslims at the present day whose ancestors were infidels a thousand years ago; this is true by and large of the Turks, the Indonesians, and sizeable Muslim populations in India and Africa. The processes by which these peoples entered Islam were varied, and reflect a phase of Islamic history when different parts of the Muslim world had gone their separate ways. Yet the core of the Islamic community owes its existence to an earlier and more unitary historical context. Between the seventh and ninth centuries the Middle East and much of North Africa were ruled by the Caliphate, a Muslim state more or less coextensive with the Muslim world of its day. This empire in turn was the product of the conquests undertaken by the inhabitants of the Arabian peninsula in the middle decades of the seventh century.

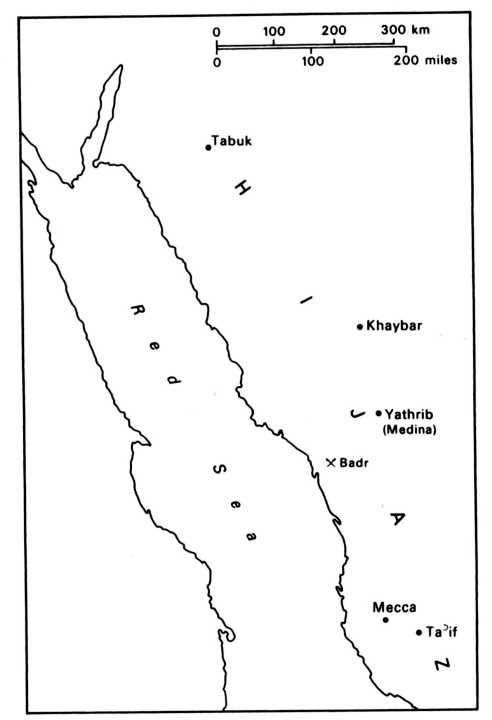

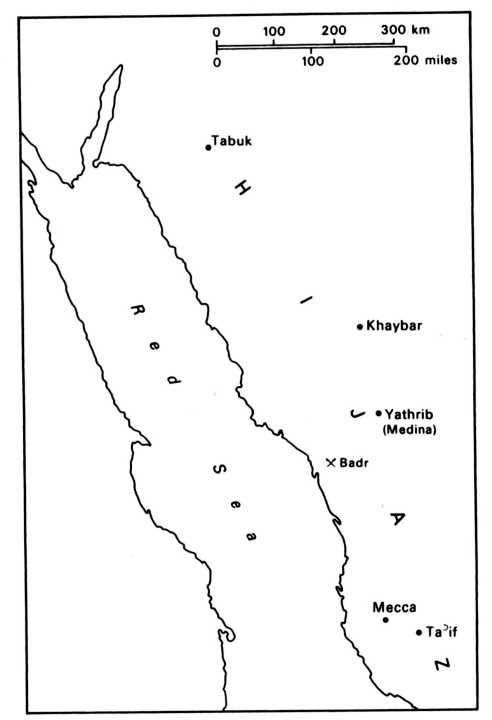

The men who effected these conquests were the followers of a certain Muhammad, an Arab merchant turned prophet and politician who in the 620s established a theocratic state among the tribes of western Arabia.

The Middle East

Western Arabia

1 Background

Monotheism

Muhammad was a monotheist prophet. Monotheism is the belief that there is one God, and only one. It is a simple idea; and like many simple ideas, it is not entirely obvious.

Over the last few thousand years it has probably been the general consensus of human societies that there are numerous gods (though men have certainly held very different views as to who these gods are and what they do). The oldest societies to have left us written records, and hence direct evidence of their religious beliefs, were polytheistic some five thousand years ago; by the first millennium BC there is enough evidence to indicate that polytheism was the religious norm right across the Old World.

It did not, however, remain unchallenged. In the same millennium ideas of a rather different stamp were appearing among the intellectual elites of the more advanced cultures. In Greece, Babylonia, India and China there emerged a variety of styles of thought which were noticeably more akin to our own abstract and impersonal manner of looking at the world. The tendency was to see the universe in terms of grand unified theories, rather than as the reflection of the illcoordinated activities of a plurality of personal gods. Such ways of thinking rarely led to denial of the actual existence of the gods, but they tended to tidy them up in the interests of coherence and system, or to reduce them to a certain triviality. (Consider, for example, the view of some Buddhist sects that the gods are unable to attain enlightenment owing to the distracting behaviour of the goddesses.) What they did not do was to pick out from the polytheistic heritage a single personal god, and discard the rest.