Chapter One

The War Within

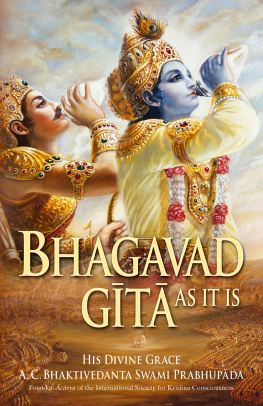

Sri Krishna consoles and instructs Prince Arjuna as he is about to go into battle against family and friends to defend his older brothers claim to the ancient throne of the Kurus. Thus the great scripture called Bhagavad Gita, the Song of the Lord, begins. Sri Krishna is Bhagavan, the Lord, the mysterious incarnation of Lord Vishnu, the aspect of God who fosters and preserves the universe against the forces constantly working to destroy and corrupt it. Krishna has appeared on earth as a royal prince of the house of the Yadavas; thus he combines earthly majesty with a hidden spiritual power. Most know him only as an unimportant prince, but the wise have seen him reveal his power to destroy evil and protect the good.

The battle of the Bhagavad Gita is not Krishnas fight, however; it is Arjunas. Krishna is only Arjunas charioteer and advisor. He has promised Arjuna that he will be with him throughout the ordeal, but much as he passionately hopes for Arjunas victory, he has sworn to be a noncombatant in the struggle. A charioteers position is a lowly one compared to the status and glory of the warrior he drives, but Krishna assumes this modest role out of love for Arjuna. As charioteer, he is in a perfect position to give advice and encouragement to Arjuna without violating his promise not to join the fight himself.

To secure their claim to the throne, Arjuna and his brothers must fight not an alien army but their own cousins, who have held the kingdom for many years. Tragically, the forces against them include their own uncle, the blind king Dhritarashtra, and even the revered teachers and elders who guided Arjuna and his brothers when they were young. Arjuna, of course, wants to win the throne for his brother, who is the rightful heir to the Kuru dynasty and has endured many wrongs. But he is dismayed at the prospect of fighting his own people. Thus, on the morning the great battle is to begin, he turns to Krishna, his friend and spiritual advisor, and asks him the deeper questions about life that he has never asked before. The Bhagavad Gita is Krishnas answer.

Other warriors who appear elsewhere in the drama are mentioned in this first chapter of the Gita. To Indians these are familiar figures from the legendary past, but to most Western readers they will be unknown and even unpronounceable names. Arjuna and his brothers are known as the Pandavas, the sons of Pandu: Yudhishthira, Bhima, Arjuna, Sahadeva, and Nakula. The other side is called the Kauravas, the sons of Kuru. This is somewhat misleading, for both sides of the royal family are Kurus by birth. But the Pandavas are now in the position of appearing to be the dissident faction, so they are called sons of Pandu to distinguish them from the larger family.

Pandu was once king of the kingdom of Hastinapura, but he retired into the forest on spiritual retreat and died young. His elder brother, Dhritarashtra, was blind since birth, so he was never named ruler, but he did share power with his brother. When Pandu died his eldest son, Yudhishthira, should have succeeded him; but because Yudhishthira was only a boy, Dhritarashtra continued on after Pandus death.

As time passed, however, Dhritarashtras attachment to his own eldest son, Duryodhana, gradually overcame him. Instead of rising to royal impartiality and allowing Yudhishthira his fair claim, the old, blind king began to connive at his sons demand to succeed to the throne. Actually, the line of succession had grown convoluted over several generations, and it was not unthinkable that Duryodhana should rule next. But Yudhishthiras outstanding qualities and Duryodhanas corruption gradually decided the issue, at least from the moral point of view. For Duryodhana, the conflict could be resolved only on the battlefield.

Other warriors are mentioned briefly in chapter 1. Two particularly important figures in the Mahabharata story are Drona and Bhishma. Drona was born a brahmin, a member of the priestly caste, but in search of wealth he took up the way of the warrior and excelled in the knowledge of arms. He was the teacher, the guru, of all the royal princes in their youth, the sons of Pandu and the sons of Dhritarashtra alike. Thus it was he who taught both sides the skills of war an irony which sharp-tongued Duryodhana points out in verse 3. Arjuna was Dronas best pupil when it came to the bow, excelling even Dronas own son, Ashvatthama.

Bhishma, the grandsire of both sides, is not actually the princes grandfather but a respected elder statesman. As Dhritarashtras advisor of many years standing, he considers it his duty to stand by his king and try to protect him from his weaknesses and wrong decisions.

Another figure introduced in chapter 1 is Sanjaya, who narrates the entire Gita to the blind king Dhritarashtra. Sanjaya is not present on the battlefield, but the text tells us that the sage Vyasa, the composer of the Gita, has given him divine sight so that he can see and report everything.

Chapter 1 leaves us acutely aware that we are on a battlefield, waiting for a catastrophic war to begin; but once Krishna begins his instruction, we leave the battlefield behind and enter the realms of philosophy and mystical vision. The first chapter is but a bridge to the real subjects of the Gita, and thus need not detain us too long in our study of the poem.

Yet the first chapter has caused a great deal of debate, largely because of what it has to say about the morality of war. Basically there have been two points of view, which are almost (but perhaps not completely) irreconcilable. First, there is the orthodox Hindu viewpoint that the Gita condones war for the warrior class: it is the dharma, the moral duty, of soldiers to fight in a good cause, though never for evil leaders. (It should be added that this is part of an elaborate and highly chivalrous code prescribing the just rules of war.) According to this orthodox view, the lesson of the Mahabharata (and therefore of the Gita) is that although war is evil, it is an evil that cannot be avoided an evil both tragic and honorable for the warrior himself. War in a just cause, justly waged, is also in accord with the divine will. Because of this, in the Mahabharata, Yudhishthira and his noble brothers find their peace in the next world when they have finished their duty on earth.

The mystics point of view is more subtle. For them the battle is an allegory, a cosmic struggle between good and evil. Krishna has revealed himself on earth to reestablish righteousness, and he is asking Arjuna to engage in a spiritual struggle, not a worldly one. According to this interpretation, Arjuna is asked to fight not his kith and kin but his own lower self. Mahatma Gandhi, who based his daily life on the Gita from his twenties on, felt it would be impossible to live the kind of life taught in the Gita and still engage in violence. To argue that the Gita condones violence, he said, was to give importance only to its opening verses its preface, so to speak and ignore the scripture itself.

For some, it helps clarify this question to look upon the Gita as an Upanishad, a mystical statement from the Vedas, that was incorporated into the warrior epic of a later age. Chapter 1 of the Gita then forms a rather perilous bridge between the warriors world and the essential part of the Gita Sri Krishnas revelations of spiritual truth. D.M.

1: The War Within

DHRITARASHTRA

O Sanjaya, tell me what happened at Kurukshetra, the field of dharma, where my family and the Pandavas gathered to fight.

SANJAYA

Having surveyed the forces of the Pandavas arrayed for battle, prince Duryodhana approached his teacher, Drona, and spoke. O my teacher, look at this mighty army of the Pandavas, assembled by your own gifted disciple, Yudhishthira. There are heroic warriors and great archers who are the equals of Bhima and Arjuna: Yuyudhana, Virata, the mighty Drupada, Dhrishtaketu, Chekitana, the valiant king of Kashi, Purujit, Kuntibhoja,the great leader Shaibya, the powerful Yudhamanyu, the valiant Uttamaujas, and the son of Subhadra, in addition to the sons of Draupadi. All these command mighty chariots.