HAMLET IN PURGATORY

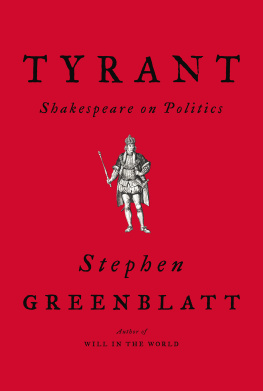

STEPHEN GREENBLATT

Hamlet in Purgatory

With a new preface by the author

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2001 by Princeton University Press

Preface copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

First printing, 2001

First paperback printing, 2002

First Princeton Classics edition, 2013

Library of Congress Control Number 2013937134

ISBN 978-0-691-16024-5

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Ramie

ILLUSTRATIONS

PLATES

(following p. 52)

FIGURES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

AS IS APPROPRIATE for a book about Purgatory, I have benefited greatly from the kindness of loved ones, friends, and strangers. I have deep debts of gratitude to both institutions and individuals who have helped me bring this project to completion. An invitation to deliver the University Lectures at Princeton University provided me with the key incentive to work out my ideas, and I received helpful criticism, suggestions, and encouragement from many friends there, including Oliver Arnold, Lawrence Danson, Anthony Grafton, Alvin Kernan, and Froma Zeitlin. A year at the marvelous Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin was invaluable. The Rektor, Prof. Dr. Wolf Lepenies, the superb staff, and the intense intellectual stimulation of the Kolleg created an ideal space for research and writingand the fact that Berlin is haunted by ghosts was itself a powerful inducement to reflect on the claims of the dead and the obligations of the living. I have been fortunate in other institutional supports as well, including the extraordinary resources of the British Library, the Getty Library in Los Angeles, and the Houghton and Widener Libraries at Harvard University. The intellectual seriousness and high distinction of my colleagues and students at Harvard have been equally remarkable resources. A residence at the Rockefeller Foundation Study and Conference Center in Bellagio and a Corrour Symposium enabled me to think and write in almost absurdly beautiful surroundings.

Now, as in the past, I have been struck by the remarkable intellectual generosity of scholars. I have had the opportunity to present pieces of this book as lectures, and on each and every one of these occasions I have profited greatly from advice and argument, often pursued in subsequent e-mail exchanges. I particularly want to thank the Medical Anthropology and Cultural Psychiatry Research Seminar at Harvard University; the Seminar on Society, Belief, and Culture in the Early Modern World at the University of London; the Center for Research in Early Modern History, Culture, and Science at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universistat in Frankfurt; the conference on Rituale Heute at the University of Zrich; the conference on Lancastrian Shakespeare at Lancaster University; the New Europe College in Bucharest, Romania; the Center for Literary Studies at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem; Kyoto University, Tokyo University, and the Suntory Foundation in Japan; and the Indian Institute of Technology and the Indian Academy of Letters in New Delhi.

The list of individuals who have helped me could be extended for many pages, but I will content myself with naming a few whose assistance with this book has been particularly important to me: Homi Bhabha, Natalie Zemon Davis, Philip Fisher, Carlo Ginzberg, Valentin Groebner, Richard Helgerson, David Kastan, Jeffrey Knapp, Joseph Koerner, Lisbet Koerner, Thomas Laqueur, Franois Laroque, Franco Marenco, J. Hillis Miller, Robert Pinsky, Peter Sacks, Elaine Scarry, Pippa Skotnes, Nicholas Watson, and Bernard Williams. Debora Shuger brought to the whole manuscript her characteristic spiritual intensity, rich learning, and penetrating intelligence. John Maier and Gustavo Secchi have been indefatigable and resourceful research assistants; Beatrice Kitzinger and John Lopez made many valuable suggestions. As always, my sons, Josh and Aaron, have listened patiently, asked crucial questions, and prodded me in new directions. It seems appropriate too, given my subject, to reflect with gratitude on all I owe to my father, who died in 1983, and to my mother, who diedit pains me to writejust as I was finishing this book.

I have left for last my acknowledgment of the deepest bond, the most cherished indebtedness, to the person who has been essential in every way to meeting the challenges and sharing the pleasures of this project: my wife, Ramie Targoff.

PREFACE

AROUND 1600, audiences in London flocked to the Globe Theatre to see a new dramatization of a very old story, a tale of murder and revenge in medieval Denmark. Since the tale of Hamlet had already been adapted at least once before for the London stage in a play performed successfully in the 1590s, the rough outlines of the plot may have been familiar to many who bought tickets to see Shakespeares new version. But what they saw at the Globe was an unprecedented explosion of theatrical power.

That power was vividly in evidence from the plays initial words, Whos there?the most famous opening line in theater historyto the cannon-fire with which it closes. The sense that something remarkable had happened seems to have led to a heightened desire to read the tragedys script. A pirated version went on sale almost immediately, and an authorized text (Newly imprinted and enlarged to almost as much againe as it was, according to the true and perfect Coppie) appeared soon after. The play has never fallen out of favor; it remains almost eerily alive.

I set out in Hamlet in Purgatory to understand some of the sources of Hamlets power. What enabled Shakespeare to infuse so much life into his characters and why should this life seem peculiarly present where we would least expect it, in the figure of a dead man, the ghost of the murdered king? What resources did he draw upon to make the old story so fresh and so gripping? Or, as I put it to myself, into what cultural artery did he plunge his needle in order to release the startling rush of vital energy?

In undertaking the project, I did not want to put this energy back where it came fromas if that were possibleor to explain it away. I wanted to dwell in a particular literary pleasure, to heighten its wonder by burrowing down into the historical materials out of which it was produced. Those materials, I tried to show, reached deep into Renaissance English culture, into its characteristic ways of burying the dead, imagining the afterlife, negotiating with memories of the departed. The risk was that the play would disappear into the details of that culture, as in a sterile antiquarianism. But my hope was that I could instead disclose the resources upon which the playwright drew and thereby extend the field of imaginative power.

The imagination is not the exclusive possession of experts; rather, the expertsgreat writers and artistsare singularly gifted at tapping into what is circulating all around them in virtually everyone, high and low. Some are gifted as well at drawing upon what has ceased to circulate, what was once alive but now lies buried beneath the cultural soil. Shakespeare, it seemed to me, had a particular interest in digging up and redeploying damaged or discarded institutional goods, cultural memories that he returned to his contemporaries and bequeathed to the future.

Next page