Greenblatt, Stephen Jay.

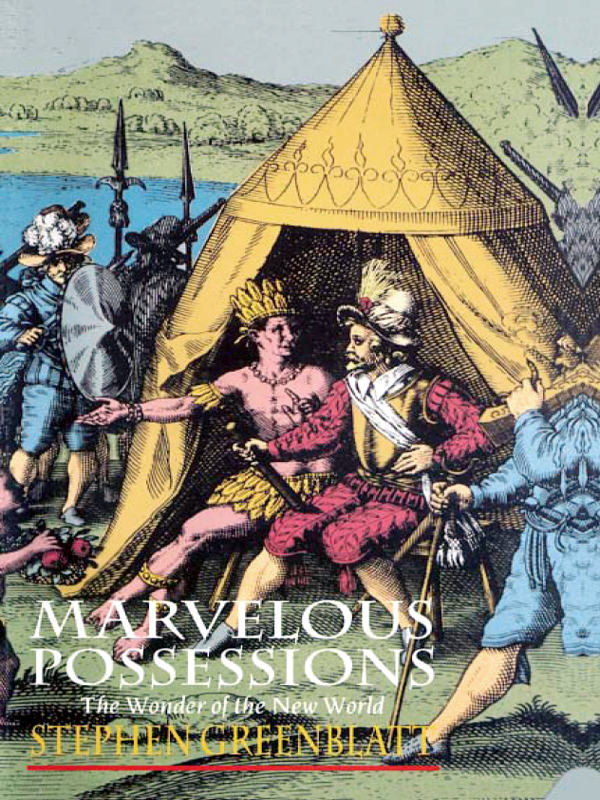

Marvelous possessions: the wonder of the New World / Stephen Greenblatt.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. AmericaDiscovery and exploration. 2. AmericaDescription and travel. 3. Marvelous, TheSocial aspects. 4. WonderSocial aspects. 5. Travel in literature. I. Title.

Acknowledgments

AS befits a study of travel writing, this book owes its existence to exotic realms beyond the borders of California: specifically, to Oxford University, where I delivered versions of these chapters as the Clarendon Lectures, and to the University of Chicago, where I gave them as the Carpenter Lectures. Both visits were for me wonderful occasions, memorable for the extraordinary kindness and generosity of my hosts. How could the visits have been anything but wonderful? Thanks to the Dean and Students of Christ Church, I spent two splendid weeks in rooms that looked out on the Meadow. Chicago in January is not quite as green and mild as Oxford in May, but it has more than ample compensations, including La Grande Jatte and one of the best blues clubs I have ever set foot in.

And the people in both places! Among the many to whom I owe substantial debts of gratitude, let me mention only a few: in Oxford, Julia Briggs, Christopher Butler, John Carey, Stephen Gill, Malcolm Godden, Dennis Kay, Don McKenzie, David Norbrook, Nigel Smith, John Walsh; in Chicago, Leonard Barkan, Camille Bennett, David Bevington, James Chandler, Arnold Davidson, Philippe Desan, Bernadette Fort, Christopher Herbert, W.J. T. Mitchell, Janel Mueller, Michael Murrin, Carol Rose, Richard Strier, Pauline Turner Strong, and Frank Thomas. I would like to give special thanks to Kim Scott Walwyn of the Oxford University Press and to Alan Thomas of the University of Chicago Press for their encouragement, attentiveness, and patience. Patricia Williams generously added her own wise editorial counsel.

There are many other places and other people with whom this book is linked: Inga Clendinnen and Greg Dening in Melbourne, Guido Fink in Bologna, Salvatore Camporeale and Louise Clubb in Florence, Wolfgang Iser and Jrgen Schlaeger in Konstanz, Michel de Certeau, Luce Giard, Franois Hartog, Louis Marin, and Tzvetan Todorov in Paris. I started to make a list of the others, closer to home, but when I filled several pages with names and had still not come to an end, I decided to abandon the attempt. The friends and colleagues who have been so generous with their time and their learning already know, I hope, what they mean to me. I must, however, at least thank by name those who have read and offered criticisms of the whole manuscript: Paul Alpers, Oliver Arnold, Sacvan Bercovitch, Homi Bhabha, Catherine Gallagher, Steven Knapp, Thomas Laqueur, Robert Pinsky, and David Quint. Rolena Adorno, Svetlana Alpers, Alfred Arteaga, Howard Bloch, Beatriz Pastor Bodmer, Theodore Cachey, Natalie Zemon Davis, Joel Fineman, Philip Fisher, Frank Grady, Ellen Greenblatt, Roland Greene, T. Walter Herbert, Jr., Jeffrey Knapp, David Lloyd, Laurent Mayali, Louis Montrose, Michael Palencia-Roth, Jos Rabasa, Michael Rogin, David Harris Sacks, Elaine Scarry, Candace Slater, Randolph Starn, Wendy Steiner, and Janet Whatley all read substantial chunks and made valuable suggestions. My research assistants, Lianna Farber, Paula Findlen, Lisa Freinkel, Wendy Ruppel, Eve Sanders, and Elizabeth Young, helped me get some control over voluminous materials that were always threatening to spin off into irremediable confusion. I also benefited greatly from the expertise of librarians at the University of California, Oxford University, the University of Chicago, Harvard University, the Bibliothque Mazarine, the Bibliothque Nationale, the British Library, the Warburg Institute, and the Newberry Library. And, of course, the University of California, Berkeley, has as usual provided not only generous support but also an immensely exciting intellectual network.

There is another place and set of people with whom this book is linked both directly and indirectly. I first drafted the chapters on Mandeville and Columbus as lectures to be given on separate occasions in Israel, the first at a conference on 'Landscape, Artifact, Text' at Bar Ilan University in Tel Aviv, the second at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Once again I want to acknowledge the hospitality, friendship, and intellectual generosity of many people, including Sharon Baris, Daniel Boyarin, Harold Fisch, Elizabeth Freund, David Heyd, Milly Heyd, Zvi Jegendorf, Ruth Nevo, and Ellen Spolsky. But I also want to acknowledge something else: the original destination of these two lectures is not a neutral fact. It never is, I suppose, for the situation or occasion of one's discourse always manages to shape its meanings, however careful, objective, and truthful one tries to be. At the end of one of my lectures in Chicago, a student challenged me to account for my own position. How can I avoid the implication, she asked, that I have situated myself at a very safe distance from the Europeans about whom I write, a distance secured by means of a sardonic smile that protects me from implication in the discursive practices I am describing? The answer is that I do not claim such protection nor do I imagine myself situated at a safe distance. On the contrary, I have tried in these chapters, not without pain, to register within the very texture of my scholarship a critique of the Zionism in which I was raised and to which I continue to feel, in the midst of deep moral and political reservations, a complex bond. The critique centers on the dream of the national possession of the Dome of the Rock and on the use of the discourse of wonder to supplement legally flawed territorial claims. The bond centers on the spiritual, historical, and psychological legacy of uprooting and genocide. Neither the critique nor the bond constitute the meaning of this bookwhich is, after all, about other times and other placesbut their pressure makes itself felt, along with the question I am still struggling to resolve: how is it possible, in a time of disorientation, hatred of the other, and possessiveness, to keep the capacity for wonder from being poisoned?

List of Illustrations

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

WHEN I was a child, my favorite books were The Arabian Nights and Richard Halliburton's Book of Marvels. The appeal of the former, even in what I assume was a grotesquely reduced version, lay in the primal power of storytelling. Some years ago, in the Djeema EI Fnah in Marrakesh, I joined the charmed circle of listeners seated on the ground around the professional story-teller and attended uncomprehendingly to his long tale. In the peculiar reverie that comes with listening to a language one does not understand, hearing it as an alien music, knowing only that a tale is being told, I allowed my mind to wander and discovered that I was telling myself one of the stories from the Arabian Nights, the tale of Sinbad and the roc. If it is true, as Walter Benjamin writes, that every real story 'contains, openly or covertly, something useful', then that tale, of diamonds, deep caverns, snakes, raw meat, and birds with huge talons, must have impressed itself upon my prepubescent imagination as containing something extremely useful, something I should never forget. The utility, in this particular case, has remained hidden from me, but I am reasonably confident that it will be someday revealed. And I remain possessed by stories and obsessed with their complex uses.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1994.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1994.