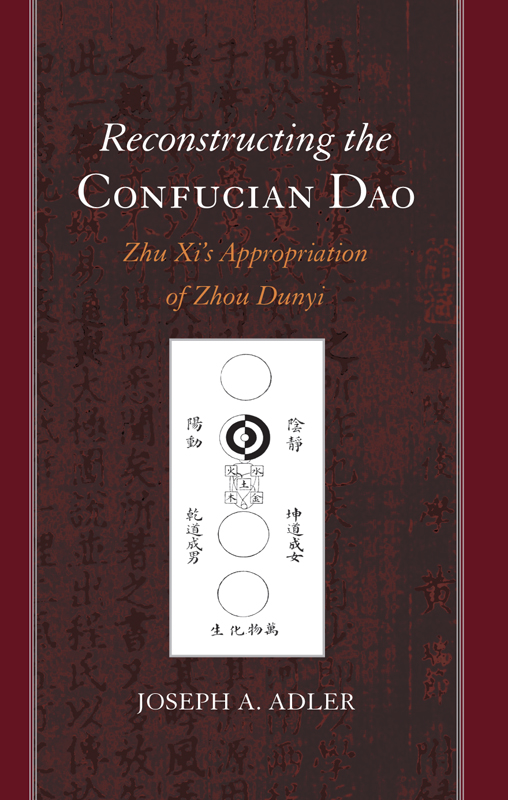

R ECONSTRUCTING THE C ONFUCIAN D AO

SUNY SERIES IN C HINESE P HILOSOPHY AND C ULTURE

Roger T. Ames, editor

Reconstructing the

CONFUCIAN DAO

Zhu Xis Appropriation of Zhou Dunyi

JOSEPH A. ADLER

S TATE U NIVERSITY OF N EW Y ORK P RESS

Published by

S TATE U NIVERSITY OF N EW Y ORK P RESS , A LBANY

2014 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production and book design, Laurie Searl Marketing, Michael Campochiaro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Adler, Joseph Alan.

Reconstructing the Confucian Dao : Zhu Xis appropriation of Zhou Dunyi / Joseph A. Adler.

pages cm. (SUNY series in Chinese philosophy and culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-5157-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Zhou, Dunyi, 10171073. 2. Neo-Confucianism. 3. Zhu, Xi, 11301200. I. Title.

B128.C44A63 2014

181'.112dc23

2013025545

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Ruth and Anna

Contents

Acknowledgments

I remember the precise moment when I began to look into Zhu Xis appropriation of Zhou Dunyi. It was in Taipei, in February 1990, and I was sitting in a bare office at National Taiwan University with my hands poised over the keyboard of an old (even at the time) IBM-compatible PC. I had not yet decided which of two options to pursue under my Language and Research fellowship at the Inter-University Program in Chinese Language Studies: to revise my dissertation for publication, or to look further into Zhu Xis use of Zhou Dunyis texts, a topic that I had touched on in the dissertation. Finding the latter more intriguing, I began translating Zhus commentary on Zhous Tongshu. The work continued sporadically over the intervening two decades, as other writing projects pushed it to the back burner. I am extremely grateful to the Inter-University Program and the Academia Sinica Committee on Scientific and Scholarly Cooperation with the U.S.A. for providing that fellowship. In 1994 I received a grant from the Pacific Cultural Foundation to continue work on the translation (. For both, and for my 200809 sabbatical leave from Kenyon College, I am extremely grateful.

I also wish to express my heartfelt thanks to those who provided feedback at various stages of this project: the late Professor Yang Youwei of Taipei, who helped me with the earliest stages of the translation; Kidder Smith Jr. and the participants in the New England Symposium on Chinese Thought at Bowdoin College for their comments in 1992 on my first attempt to make sense of Zhu Xis appropriation of Zhou Dunyi (ultimately a dead end); Philip J. Ivanhoe, for his detailed written comments in 1999 on the paper I read at the Association for Asian Studies annual meeting in Washington, D.C. (the first and providing excellent and detailed feedback; and Tu Weiming for first challenging me to work on Zhu Xi way back in 1979. Finally, I would like to thank Laurie Searl at SUNY Press for her excellent work on this project.

Part I

Introduction

The story of the early development of Neo-Confucianismthe revival of Confucianism in Song dynasty China (9601279), after eight hundred years during which Buddhism and Daoism had dominated the religious landscapehas taken pretty much a standard form ever since the late twelfth century.the cosmological basis of Neo-Confucian philosophycosmology in terms of qi (the psycho-physical stuff of which all things are composed), which has two modes of activity, yin (dark, moist, sinking, condensing) and yang (light, dry, rising, expanding).

The story continues with Zhou acting as tutor to his two nephews, Cheng Hao (10321085) and Cheng Yi (10331107), for about a year when they were teenagers. The Cheng brothers then grow up to form the nucleus of a group of Confucian thinkers in the city of Luoyang, in north-central China (Henan province). The Chengs and their many disciples come to be known as the Luo schoolusually referred to in Western scholarship as the Cheng school. They become quite influential in philosophical circles and are actively involved in government, especially as part of the conservative opposition to the reformist prime minister, Wang Anshi (10211086).

About twenty years after Cheng Yi dies, comes a catastrophe. The capital, Kaifeng, is captured by the Jurchen, a nomadic ethnic group from the northeast. The emperor is abducted. The remaining court flees to the south and establishes a new Song capital in Linan (modern Hangzhou), but the northern half of their former domain is now ruled by the Jurchen. (The dynastic era is thenceforth divided into two parts, the Northern Song [9601127] and Southern Song, which was finally conquered by the Mongols in 1279.) Some of the Chengs disciples also move south and spread their teachings there. Zhu Xi (11301200), born three years after the loss of the north, studies with some third-generation Cheng disciples and eventually, after seriously flirting with Buddhism, becomes committed to their school of thought and spreads their teachings prolifically. He becomes even more influential than the Cheng brothers, and his teachings eventually dominate those of his competitors. He combines the ideas of the Chengs and their associates with his own, creating a new synthesis called Daoxue (Learning of the Way)also called the school of principle (lixue ) or (preferably) the Cheng-Zhu school. While never without serious competition, this school dominates the later history of Chinese thought right up to the twentieth century, becoming in many peoples minds synonymous with Neo-Confucianism.

This standard history is recognized by scholars today as at best a partial view of the development of Confucian thought and practice in the Song dynasty, which was much more varied than the simplified story allows. At worst it is a reductionistic identification of Neo-Confucianism with the Cheng-Zhu school aloneperhaps admitting the Lu-Wang school as a

We also know, although it is not widely acknowledged, that the placement of Zhou Dunyi at the head of the lineage of Song sages was entirely the invention of Zhu Xi. We also know how problematic that choice was for Zhu: Zhou Dunyi was widely regarded as having strong Daoist leanings, and Zhu Xi was vehemently opposed to Daoism, at least after the 1150s. Zhous Taiji Diagram, in fact, almost certainly was given to him by his Daoist friends, and this was well known in Zhu Xis time (although he denied it). The key terms in the Discussion of the diagram, written by Zhou himself, were largely or exclusively Daoist terms (taiji and wuji). And some of Zhus colleaguesnotably the Lu brothersobjected strongly to Zhus elevation of Zhou to the position of first Confucian sage of the Song because of his Daoist connections. This dispute produced a rather bitter split between Zhu Xi and Lu Jiuyuan, who had previously been good friends.

All this raises the obvious question: Why did Zhu Xi declare Zhou Dunyi to be the first true Confucian sage since Mencius (Mengzi , 4th century BCE)? He could easily have followed the consensus of his colleagues that Cheng Hao had rediscovered the Confucian