ZHOU DAGUAN

A RECORD OF CAMBODIA

THE LAND AND ITS PEOPLE

TRANSLATED WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY

PETER HARRIS

FOREWORD BY

DAVID CHANDLER

FOR VICKY WITH LOVE

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

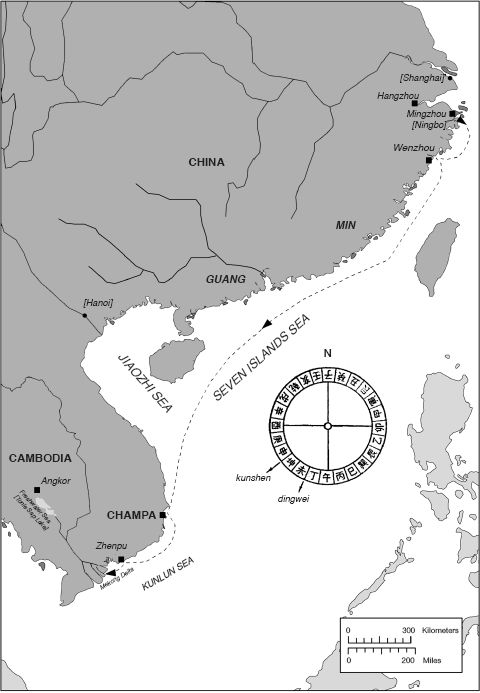

IN AUGUST 1296, Zhou Daguan (c. 1270 c. 1350), a native of Wenzhou, a coastal city south of Shanghai, arrived at Yasodharapura, the capital of Cambodia, as part of an official delegation sent by the Chinese Emperor Temr (r. 12941307).

Zhou stayed at Yasodharapura (which we know today as Angkor) for eleven months. When he returned home he composed A Record of CambodiaThe Land and Its People, perhaps as part of an official report. We know almost nothing of his subsequent career. Moreover, as Peter Harris reminds us in the introduction to his fresh and absorbing translation, what has come down to us may well be less than half of what Zhou originally wrote.

Even in its truncated form, A Record of CambodiaThe Land and Its People is the only surviving eyewitness account of daily life at Angkor. Written by an alert young foreigner with a wide range of interests, Zhous memoir has immense historical value. In Harris deft, accessible translation, it is also fun to read.

Zhous memoir was first translated into French in 1819, but it did not have much impact until 1902, when it was retranslated into French by Paul Pelliot (18781945). By the time Pelliots version appeared, Angkor had been discovered by the French and France had established its protectorate over Cambodia. Scholars of Cambodia were quick to recognize the value of Pelliots excellent translation. In his old age, Pelliot returned to Zhous memoir, and a partly revised translation appeared in 1951. This posthumous text, in turn, formed the basis for English-language translations that were published in recent years.

It has been over half a century, in other words, since Zhous original text has been revisited and over a century since it has been translated in full into a European language. In the meantime, great advances have been made in scholarship about Angkor and about thirteenth-century China. In his helpful introduction and his copious notes Harris locates Zhous memoir in the context of thirteenth-century Chinese literature and history, and places Zhous remarks about Cambodia in the context of what we know about the kingdom from a range of other sources.

Until the 1970s, archaeological work at Angkor concentrated on the temples, and writings about the kingdom stressed the activities of priests, princes, and kings; the development of artistic styles; and what can be gleaned from statuary and inscriptions about Cambodian governance and religion. What we know about everyday life, aside from Zhous account, came largely from the teeming bas-reliefs of the Bayon and, to a lesser extent, those of Angkor Wat. From a scholarly point of view, and for visitors who now number more than a million a year, Yasodharapura was a ruined, empty city, with many of its temples restored but with its people missing,

In the mid-1970s, archaeology came to a halt for over twenty years as Cambodia suffered from civil war, aerial bombardment, and the Khmer Rouge regime, as well as more than a decade of international isolation. In the mid-1990s, when archeology revived in Cambodia, many archaeologists began to concentrate on studying Yasodharapura not only from the top but also as a thriving, low density city which contained in its heyday perhaps as many as six hundred thousand people. Recent scholarly work has filled the Angkorian landscape with canals, roads, villages, and inhabitants. The new popularizing emphasis fits neatly with Zhous account, which shows us thirteenth-century Yasodharapura as a lived-in, monumental city, crowded with princes, priests, merchants, slaves, travelers, and appealingly ordinary people.

Peter Harris first visited Angkor in 1969, a year before he graduated from Oxford with first-class honors in Chinese. Since then, he has had a varied and exciting career as a scholar, a teacher, an NGO official, and a writer and producer for the BBC. Over the years, he has lived and worked in China, Indonesia, New Zealand, India, and Cambodia, where in 20052006 he directed a multi-million dollar USAID-sponsored program concerned with human rights and governance. His scholarly turn of mind, his flair for writing, and his long exposure to Asia have ideally suited him to bridge the gap between Zhous occasionally elusive classical Chinese and the mysteries of Angkor on the one hand and, on the other, the everyday people, events, and culture that Zhou so vividly brings to life.

In his edition of Zhou Daguans A Record of CambodiaThe Land and Its People, Peter Harris has given a new generation of readers a masterly version of Zhous timeless and fascinating account that scholars of Cambodia are sure to relish and visitors to Angkor are sure to enjoy.

David Chandler

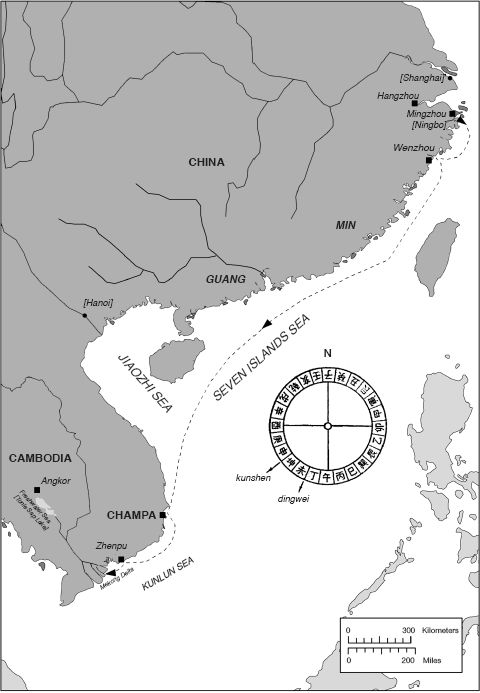

Map of Zhou Daguans outward route

PREFACE

I FIRST VISITED Angkor in June 1969, as a student of Chinese en route from Hong Kong to London. Its mysterious buildings stood silently in the surrounding forest, and were almost completely deserted. I understood almost nothing about what I was looking at. Nor did I have ready access to a guidebook. There were none of the children selling books, cards, cold drinks, and trinkets, let alone the regiment of glamorous hotels with their hooded snakes and Jayavarman statuary that now fill the Siem Reap skyline.

Like most people, I was captivated by the stillness and timelessness of Angkor. But once home I was soon distracted by other interests. I went back to Cambodia in 19811982 as the Oxfam Field Director in Phnom Penh, but Angkor was closed to visitors. Pol Pots forces were said to be billeted in some of the buildings, and there were dark stories about the war damage being done to them. (Nothing, it turned out, compared to the damage done by art thieves since then.) But I never got closer than Kampong Thom along a roadRoute 6that, like much of the country, was in ruinous condition. My time with Oxfam in Cambodia was brief, and again, I soon became involved in work elsewhere. The buildings of Angkor stayed in the back of my mind as a place to return to one day. But for the next two decades I did not give them much thought.

Then in 2004 my wife Vicky and I visited our old friend Margo Picken, who was working with the UN in Phnom Penh. One day she picked up one of the English versions of Zhou Daguans text and flourished it in the air. There was a need for an English translation from the original Chinese, she said. Why didnt I do it?

Rashly, I agreed. After all, it was only a short book. Moreover by this time I had visited Angkor a second time and rediscovered its delights. I soon found out, however, that even with the help of the Chinese scholar Xia Nais annotated edition, the work was going to take time. In the end it took many months. Even now I have hardly begun to explore the many textual, linguistic, historical, and artistic avenues that a study of Zhous work opens up.

My thanks go to Margo Picken, then, for giving me the idea of doing the translation, and for being a steady source of encouragement. Many others have offered help and advice as well. Duncan Campbell, the Chinese classicist at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, brought his wideranging knowledge and insights to bear on my rendering of the text and on materials relating to it. Helen Ibbitson Jessup found time off from her work as one of Cambodias leading art historians to take an enthusiastic interest. David Chandler at Monash University, whose very readable account of Cambodian history I found of immense help in the early stages of my work, reacted positively to my work and was kind enough to offer to write a foreword. He was also the one who put me in touch with Silkworm Books. Iulian Circo generously gave up his time to roam Angkor with his customary energy and a panoply of photographic equipment, and provided me with many new photos to draw on.

Next page