This book made available by the Internet Archive.

Foreword

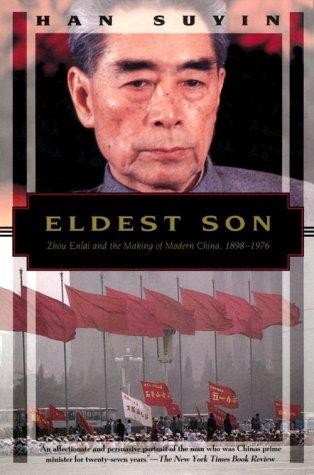

Nearly two decades after the death of Zhou Enlai, Premier of China, statesman of recognized world stature, an avalanche of articles, poems, and books continues to pour out about him, the personal memories of hundreds of Chinese who met him, worked with him, and felt the magic of the man's personality enhance their own lives. Millions of young students who have never known him yet talk of him as the most honest, the most dedicated and selfless personality in China's history. This enduring love, admiration, and respect for the man still known as "the beloved" makes writing a book about him a difficult task. I have tried to find faults, defects, in the man, and have written them down. But in China these foibles are regarded as only more evidence of his regard for others, of his willingness to see someone else's point of view, of trust and faith in others.

My thanks are due to hundreds of Chinese scholars, students, schoolteachers, working-class men and women, as well as to the dozens of men, many of them ambassadors or ministers, whom Zhou Enlai trained over the decades. I want above all to thank the Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries and its successive presidents, Chu Tunan, the late Wang Bingnan, the late Zhang Wenjing, and Han Xu, its present president, together with the staff of the Association. They all helped me through the years to gather manuscripts, to conduct interviews, to travel up and down China. I also thank many English, Indian, American, and French friends, among them Dick Wilson, Ambassador P. K. Bannerjee, James Reston, the late Ambassador Etienne Manoel Manach, for their contribution.

I also want to thank all those, both Chinese and from outside China, who so generously sent me their own memoirs concerning their meetings with Zhou Enlai. All these will be carefully stored

in the author's archives, deposited in Special Collections, Mugar Memorial Library, Boston University.

Last, but not least, I want to thank Upton Birnie Brady, who plodded patiently through a thousahd pages of the original manuscript and cut it down to manageable size for a Western audience. This has meant leaving out many of the Chinese whom I interviewed, but they will not feel chagrined, because the original version in Chinese contains their names. But in the West, Chinese names still confuse a great many readers, and Upton and I trimmed down what we felt might make the book too academic for the reader with only slight knowledge of China.

H.S.

ELDEST SON

Note on Genealogical Tabk

Every Chinese familyeven peasant families, as soon as they lift themselves out of illiteracykeeps a genealogy book, which is patrilineal, based only on the male offspring in any family.

The book of the Zhou clan in Shaoxing, Zhejiang province, goes back several centuries.

In this abridged table, only that part of the family descended from Zhou Panlong, who left Shaoxing and settled in Huai An, Jiangsu province, is recorded.

An exception is made for Zhou Yiqian, because Zhou Enlai had a good deal of connection with him, although Yiqian was a descendant of another grandfather, one of Zhou Panlong's brothers.

In China the family name comes first, and then the personal name.

In each generation, the same ideogram in a two-ideogram combination makes up an individual's personal name. This is a kind of coding, which enables the familiesextended families sometimes number up to seven hundred or eight hundred individuals in two or three generationsto know immediately which generation a family member belongs to. This is very important in the hierarchy of families, which is governed by a strict Confucian code.

a <

I

X

C

o

w

CO

H

-ID

< 0

as.!

u s

8l3g

>-< ON

Nee

i

&C o oo

w D

D 0 I

N

2--i "

oo ' oo s

C S

<^ r

^ .s S

o

>: ^^3 -s SB

^ I "O w ^

os-g fa

DC oo 0^

o

s ^

o

N

C

I-- o

2 o

w G

s

G 3

-o

G u

<

-G

^ OO rv.

I S

C N

< g

22 w ^

o a

DC

N"3

o

D

^ oo D l

os

DC os

o

I

CO

D I

OS

DC os N C

O o o DC cn o N w c

d so

oo^ ^

O^-g 2 o

DC S w

O < DC U

o

2 wo

Oh

N N N N N N

*> J 1

o N

U

H 2

N

EQ

I

1898-1924

Youth, adolescence, and education

The Russian Revolution

The May 4, 1Q1Q, Movement

Travel to Europe

The founding of the

Chinese Communist Party

March 5, 1988

A cold wind bit our faces, swept across the stubble fields and the drained marsh. We stood on a leveled square marked by chalk strips. Half a mile away the pink brick villages began, their inhabitants, standing in front of the houses, watching the small gathering we made. At one end of the square was a large bamboo screen covered with white flowers, the flowers of mourning. But it was topped by a bright red silk banner proclaiming: COMMEMORATION OF THE NINETIETH BIRTHDAY ANNIVERSARY OF THE LATE BELOVED PRIME MINISTER ZHOU ENLAI.

Beloved Premier Zhou. Automatically, so many of my generation spoke of him thus, running the words together. But perhaps our grandchildren would no longer understand why so many millions had loved him. The world was changing, China was changing. How much would be left of the memory, and the work, of Zhou Enlai in, say, another ten years?

From the flowered screen his portrait looked down upon our neat ranks. A glossy enlarged photograph, retouched. Only the eyes seemed real; they held both quizzical watchfulness and challenging mirth. The mouth was recognizable, with that half smile which seemed so spontaneous, and efficiently masked so much private agony.

Had Zhou Enlai been alive, he would not have smiled. He would have been angry, with that cold anger when his voice was lowered, not raised. He would have forbidden our gathering, for he had wanted no monument, no tomb, no grave, no stela, nothing to remember him by. "Let my ashes be scattered on the mountains and rivers of my country," he had said, and this had been done, so that not even a handful of dust remained to be enthroned anywhere.