Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

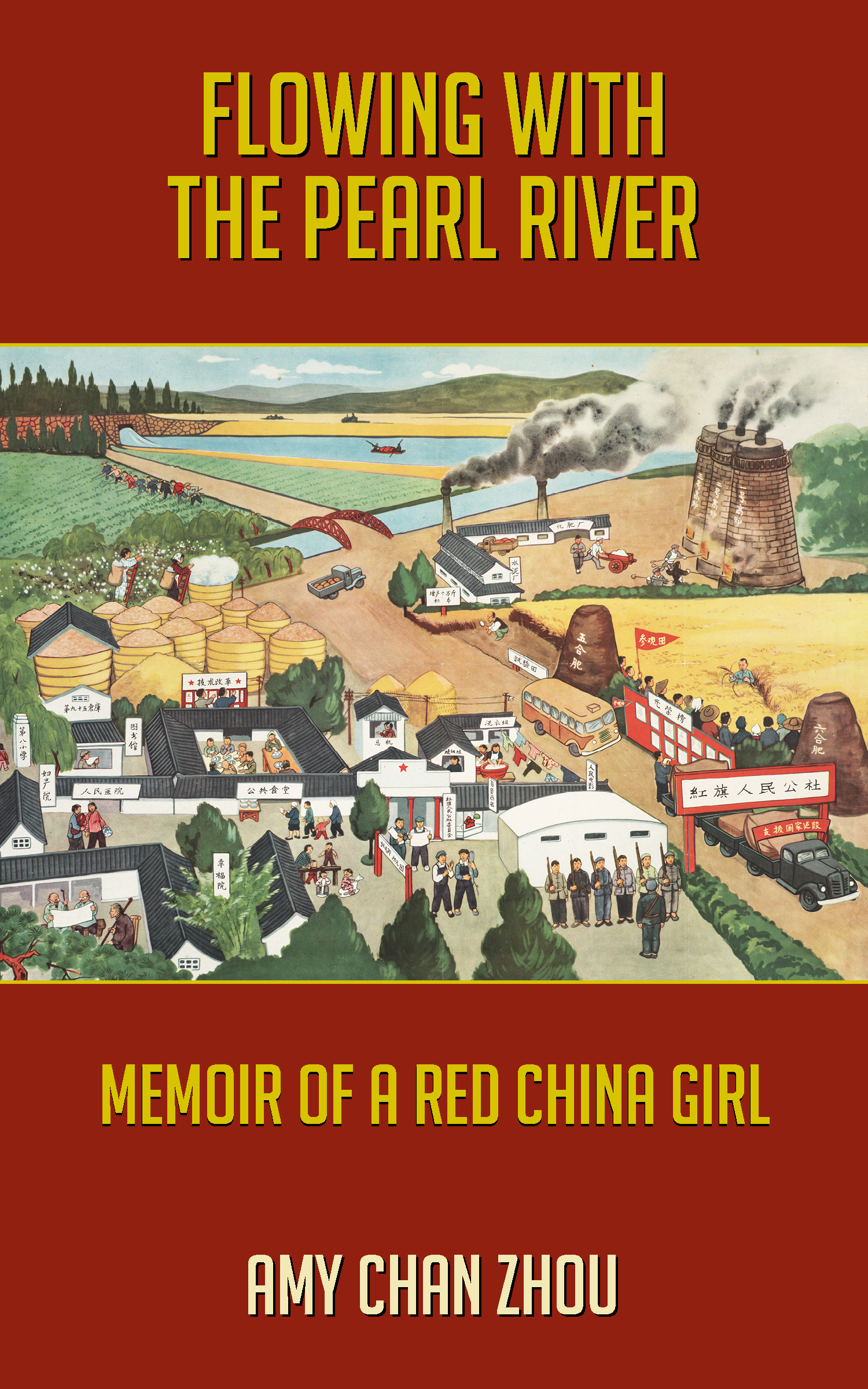

FLOWING WITH THE PEARL RIVER

MEMOIR OF A RED CHINA GIRL

AMY CHAN ZHOU

This book is a work of creative nonfiction. The events are portrayed to the best of the authors memory. While all the stories in this book are true, in certain instances, the author has compressed events, and some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

Copyright 2022 Amy Chan Zhou

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part or in any form or format without the written permission of the publisher.

Published by Santa Monica Press LLC

Published by Santa Monica Press LLC

P.O. Box 850

Solana Beach, CA 92075

1-800-784-9553

www.santamonicapress.com

Printed in the United States

ISBN-13 978-1-59580-106-7 (print)

ISBN-13 978-1-59580-782-3 (ebook)

Publishers Cataloging-in-Publication data

Names: Zhou, Amy Chan, author.

Title: Flowing with the Pearl River : memoir of a red China girl / by Amy Chan Zhou.

Description: Solana Beach, CA: Santa Monica Press, 2022.

Identifiers: ISBN: 978-1-59580-106-7 (print) | 978-1-59580-782-3 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH Zhou, Amy Chan. | Chinese Americans--Biography. | Chinese--United States--Biography. | Immigrants--China--Biography. | Immigrants--United States--Biography. | Communism--China--History. | China--Politics and government. | BISAC YOUNG ADULT NONFICTION / Biography & Autobiography / Cultural, Ethnic & Regional | YOUNG ADULT NONFICTION / Family / Multigenerational | YOUNG ADULT NONFICTION / History / Asia | YOUNG ADULT NONFICTION / Social Topics / Emigration & Immigration | YOUNG ADULT NONFICTION / Social Science / Politics & Government | YOUNG ADULT NONFICTION / People & Places / United States / Asian American

Classification: LCC E184.C5 Z46 2022 | DDC 973.04951/092--dc23

Cover and interior design and production by Future Studio

Cover image: The Peoples Communes Are Good courtesy of The IISH collection, www.chineseposters.net

CONTENTS

WHEN I WAS YOUNG, each time my familys older generation told me something about the past, I took it for granted and most times did not pay attention. Years passed by, and I too, became a mother. Every time I visited my mothers home in Brooklyn, New York, she would sit in front of her old Singer sewing machine, using her rough fingers to measure a piece of cloth. Her wrinkled hands reminded me of how much she had gone through, and yet she insisted on making pants for my children.

While she was sewing, she spoke simply, yet disjointedly. Her miserable past experiences included the Great Famine, my fathers imprisonment and exile to labor camps, the Cultural Revolution, and, perhaps most difficult of all, the inability for our family to get residence status, which meant that we would not receive any coupons to buy food, effectively banishing us to the countryside. Sometimes, she spoke as if something blocked her throat, and then she would suddenly stop herself.

As I grew older, the desire to learn more about my familys history grew stronger. During the course of writing this memoir, I often experienced heart-wrenching emotions as I revisited my childhood days, but my desire to find the missing and broken pieces of my familys history and put them back together kept me going. I needed to learn and understand this part of my life and my ancestors lives, and I share it with you, dear reader, before the old generations are gone.

AMY CHAN ZHOU

CHAPTER 1 MY GRANDPARENTS LOVE

I WAS SENT TO THE COUNTRYSIDE to live with my maternal grandparents when I was only one year old. Their house was less than a half-mile away from a branch of the Pearl River in southern China. Tall levees were built along each side of the river; palm trees grew neatly on both sides of the levee. It was a beautiful, secluded spot. Connected by the river, a canal passed through my grandmas village like a silver belt. On each side of the canal there was a lot of bamboo. The small shoots were as big as a broomstick, and the big ones were as tall as a three-story building. Village houses lay along the canal. There were many ponds, large and small, next to the houses. As such, the village was like a water village. My grandparents house was nearly surrounded by a huge pond. On the other side of the pond was a litchi orchard, which used to belong to my grandparents and later belonged to the Peoples Commune. Beyond the orchard there were miles of paddy fields.

The house had three bedrooms. I slept in my grandparents room. The house was old, in bad shape, and built with mud and some small bricks, but it housed many pieces of beautiful, fancy furniture. The bed I slept in with my grandparents was a big redwood antique that had a roof. All the posts and legs were carved with dragons and clouds.

I still could not walk normally at age three because my bones were weak. I remember that Gong Gong (Grandpa) always brought me candy when he came home. Later, when he went out, I would block him by the door, so he would put me on his neck, and I grabbed his hair to hold on as we walked to the village. On a sunny day, Gong Gong would bring two antique hardwood chairs to a flat area in the yard. He sat on one chair, and Po Po (Grandma) would put me into the other chair. I could not sit or crawl on the ground because the bugs would bite my legs. I still remember watching little ants crawling in the gap of the bricks on the ground. As time went on, my grandfather could not sit that way anymore because he got weak and then weaker. I saw him lying on a reclining lounge chair all the time. He enjoyed it when I rubbed and patted his legs with my little hands; I was proud I could make him happy.

Po Po, my maternal grandmother, was the center of my life. She had a kindly and amiable face with big eyes. Her hair was dark gray and tied in a knot. That made her show off two long ears that people admired very much because people believed long ears brought good luck and long life. Indeed, she always had very good health and was energetic. She also had a big light pink birthmark on her right cheek that people believed would bring prosperity, so she was always welcomed by all the village families. She was very wise, kind, caring, and generous to everybody. She taught her children never to argue with other people even if they were being unreasonable. She used to say: If you are one-hundred percent right, you have to admit that you are only sixty percent right so you always leave some room for others. Arguing with others is always a losing game. One time I traveled with her to the next town. We saw a skinny beggar in front of a store; she took out 0.50 yuan and gave it to him. After we walked away, she said to me, Aa Jade, when you grow up and have money, always give some to the people who need it.

I felt that I was very special to her. Po Po always saved the best stuff for me. She had two dozen grandchildren, but she brought only me whenever she visited relatives and friends. Sometimes, when I went out with her on the street, people came out to greet us and invited us into their homes. Then they usually asked Po Po for some advice on raising kids or about medicinal remedies to treat disease. Po Po always had answers. I remember she picked some wild grass whenever anyone got sick in the family. My happiest days were going out with her. She liked to visit her cousins in the town of Zhongshan, which was about eighteen kilometers from our home. She used to travel by getting free rides in passing vehicles since only a few buses went to town each day. Whenever she saw a vehicle passing by, she raised her arm, and then the drivers used to stop next to us because we were very old and very young. I have been in a truck full of pigs and chickens and even logs. Once we reached her cousins home, we were always welcomed, then I would have a nice meal with a little meat. Normally, we didnt have any meat at home.