WHEN JESUS BECAME GOD

When jesus BECAME GOD

The Epic Fight over Christs Divinity in the Last Days of Rome

Richard E. Rubenstein

HARCOURT BRACE & COMPANY New York San Diego London

Copyright 1999 by Richard E. Rubenstein

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by anr -means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, w ithout permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to: Permissions Department, Harcourt Brace & Company, 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rubenstein. Richard E.

When Jesus became God : the epic struggle over Christ's divinity in the last day's of Rome / by Richard E. Rubenstein. 1st ed. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-15-100368-8 1. jesus ChristDivinityHistory of doctrinesEarly church, ca. 30600. 2. Arianism. 1. Title.

BT216.R83 1999

273.4dc21 98-52097

Text set in Fairfield Medium Designed by Camilla Filancia

Printed in the United States of America First edition A C E D B

FOR HANNAH AND SHANA, WITH LOVE AND ADMIRATION

Again and again in the writings of the Eastern Fathers there appears this singular devotion to the dignity of man, an attitude which survives in the Offertory in the Mass: O God, who didst marvelously create the dignity of human nature:

ROBERT PAYNE

The Fathers of the Eastern Church

Contents

Preface

This BOOK was conceived in an unusual setting.

The year was 1976. I had just arrived with my family in Aix-en-Provence, France, where I was to spend a sabbatical year teaching at the university. We had rented a house for the year from Michel Vovelle, a well-known French historian who was just packing up to leave for a sabbatical year of his own at Princeton. The lease was for a certain rent, quite reasonable, but with a proviso that if I wanted to use Professor Vovelles private library, the rent would be a bit higher. After greeting hima man with whom one felt immediately at easeI asked to see the library.

It was a rectangular room decorated in simple Provencal style, running the whole length of the house. A tall, built-in bookshelf crammed with volumes covered one long wall. The wall opposite was fully windowed, windows thrown open to admit the warm September air. From Professor Vovelles desk one could see a garden with shrubs and an olive tree. Just beyond the garden a stream murmured and splashed as if auditioning for the part of gurgling brook in some Arcadian drama. My normally frugal wife took in the room at one glance and whispered, Rent it!

We signed the amended lease, and that evening I explored the contents of the bookshelves. There were small collections on dozens of subjects, reflecting my landlords wide-ranging interests, but a great many books dealt with theology and Church history. I recalled that Michel Vovelle was widely known for his work on the "de-Christianization of France prior to the French Revolution, a sensitive blend of social and religious history that had helped define the new French scholarship. A number of titles piqued my interest, and I was sitting at the desk riffling through half a dozen books when he returned to pick up his remaining suitcases.

"So, already you are studying," he remarked amiably.

Yes. I m very happy to have the use of your library. By the way, what do you know about the Arian controversy? Ive just been reading about it.

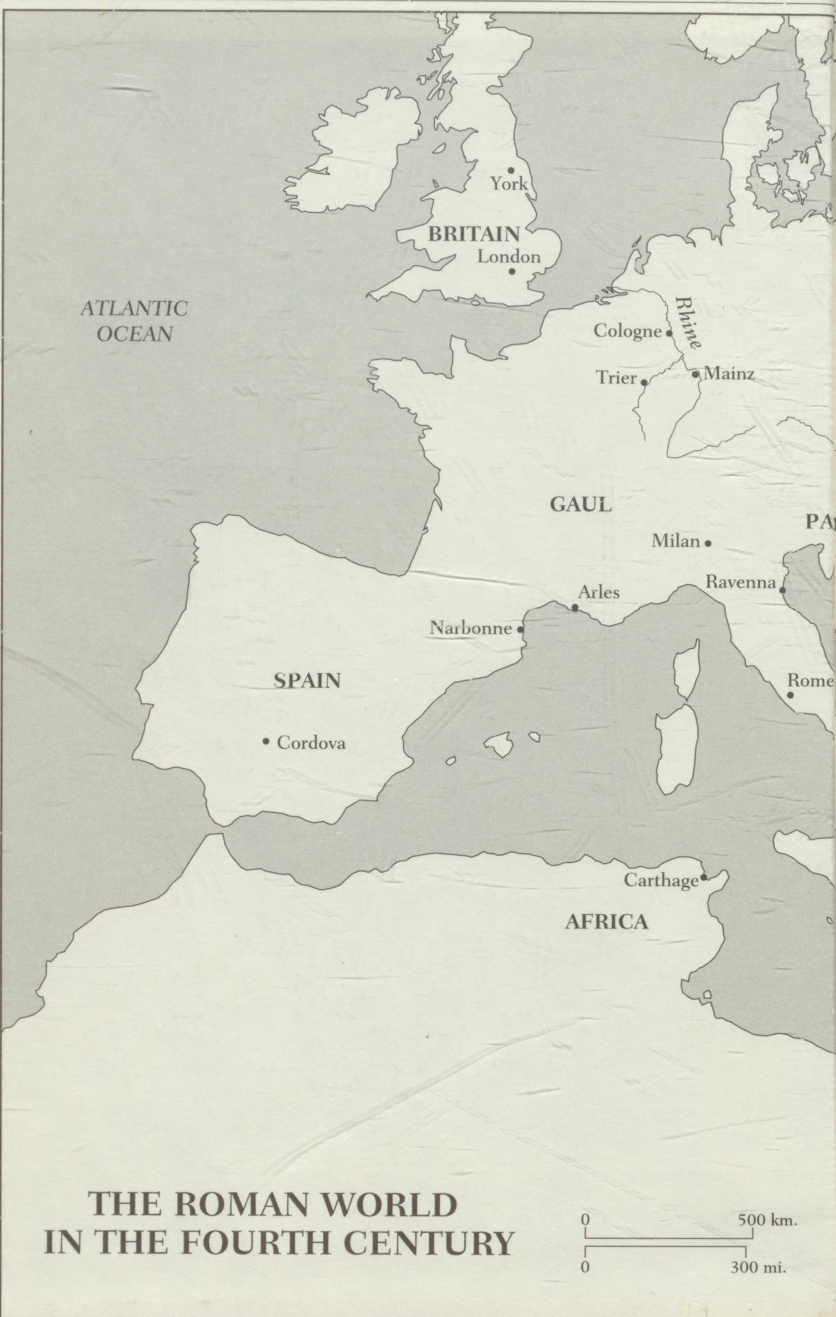

"Ah, 'I affaire Ariiis he replied. "You must learn all about it. W as Jesus Christ God on earth, or was he something else? Three hundred years after the Crucifixion, Christians still had not made up their minds about this. The Arian controversy! It is the most interesting debate in the West until the struggle between Stalin and Trotsky.

I was hooked. That year, I read most of Vovelles books on "laffaire Arius," and for years afterward, interrupted by other writing projects and life-altering events, I continued to investigate the fascinating story'. The sources of information were plentiful, although most books and articles were aimed at a narrow audience of scholars interested in the history of Catholic doctrine. Almost everything I wanted to read was written in Fnglish or French, languages that I understand, and I was able to discuss the meaning of certain important Greek terms with experts in that language. Church historians, theologians, and clergy were happy to answer my questions, as were scholars interested in the later Roman Empire.

Several times I began writing the book that I had already entitled When Jesus Became God, but something always prevented me from continuing. The problem was not just competing interests. I suppose it was self-doubt. What business did an American

Jew have writing about the divinity of Jesus Christ? How could I presume to meddle in sensitive matters concerning other peoples faith: Beneath these questions dwelled another, more difficult to answer. What drew me so strongly to explore the subject of Jesus identity and mission?

Answers began to emerge during a second sabbatical year, this time on the island of Malta, a nation of about 350,000 people of whom more than 300,000 are Roman Catholics. The head of the University of Maltas sociology department, where I taught courses on conflict resolution, was a wise, amiable, energetic Catholic priest named Joe Inguanez. Father Joe looked at me a bit quizzically when I asked him to help me locate materials on Arianism at the university library. The library did have an unusually fine eolleetion on early Church history, he said. But why did 1 want to study that particular heresy?

The explanation 1 proffered was accurate but impersonal. I have spent most of my professional life writing about violent social conflicts. To conflict analysts, intense Teligious conflict is still a great mystery. Virtually none of us predicted the current upsurge in violent doctrinal disputes around the world. The current civil war in Algeria, the struggle between ultraorthodox nationalist Jews and other groups in Israel, even the conflicts over abortion and homosexuality in the West strike many observers as weird throwbacks to a more primitive age. Religious fanaticism" is offered as their cause, as if that phrase could explain why people are motivated at some times and places (but not others) to kill each other over differences of belief.

I told Father Joe that my interest was in exploring the sources of religious conflict and the methods people have used to resolve it. 1 wanted to examine a dispute familiar enough to westerners to involve them deeply, but distant enough to permit some detached reflection. The Arian controversy, which was probably the most serious struggle between Christians before the Protestant Reformation, seemed to fit the bill perfectly....

Joe nodded, but he knew that my account was incomplete.

And?

And theres something else, I responded with some hesitation. 1 am a Jew born and raised in a Christian country. Jesus has been a part of my mental world since I was old enough to think. On the one hand, I have always found him an enormously attractive figure, challenging and inspiring. On the other... Joes raised eyebrows demanded that I continue.