Praise for Simon Critchley's

THE BOOK OF

DEAD PHILOSOPHERS

A provocative and engrossing invitation to think about the human condition and what philosophy can and can't do to illuminate it.

Financial Times

Concise, witty and oddly heartening.

New Statesman (A 2008 Book of the Year)

Full of wonderful absurdities Extremely enjoyable.

The Independent (London)

Simon Critchley is probably the sharpest and most lucid philosopher writing in English today.

Tom McCarthy, author of Remainder

Ingenious Packed with great stories.

Time Out London

A tremendous addition to an all too sparse literature Brilliant, entertaining, informative.

New Humanist (UK)

A fabulous concept [Critchley writes] with dash, humour and an eye for scandalous detail.

The Vancouver Sun

[Critchley is] among the hippest of (living) British philosophers.

The Book Bench, newyorker.com

Surprisingly good fun Worthy of the prose writings of Woody Allen Not the least of the pleasures of this odd book, lighthearted and occasionally facetious as it is, is that in surveying a chronological history of philosophers it provides a sweep through the entire history of philosophy itself.

The Irish Times

Critchley has a lightness of touch, a nimbleness of thought, and a mocking graveyard humour that puts you in mind of Hamlet with a skull.

The Independent on Sunday (London)

The Book of Dead Philosophers is something of a magic trick: on the surface an amusing and bemused series of blackout sketches of philosophers often rather humble and/or brutal deaths, it actually is an utterly serious, deeply moving, cant-free attempt to return us to the gorgeousness of material existence, to our creatureliness, to our clownish bodies, to the only immortality available to us (immersion in the moment). I absolutely love this book.

David Shields, author of The Thing About Life Is That One Day You'll Be Dead

[Critchley] brings the deaths of his predecessors to life in 190 or so energetic bursts.

The Sunday Herald (UK)

Critchley gives the nonspecialist, the reader for pleasure, a point of access into complex material.

The Sydney Morning Herald (Australia)

Simon Critchley's book looks death in the face and draws from the encounter the breath of life. No philosopher can pull a more welcome rabbit out of a more forbidding hat and Mr. Critchley does so in a prose style that is as deft as his intelligence.

Lewis Lapham, editor of Lapham's Quarterly

Simon Critchley

THE BOOK OF

DEAD PHILOSOPHERS

Simon Critchley is Professor and Chair of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York. He is the author of many books, most recently, On Heidegger's Being and Time and Infinitely Demanding: Ethics of Commitment, Politics of Resistance. The Book of Dead Philosophers was written on a hill overlooking Los Angeles, where he was a scholar at the Getty Research Institute. He lives in Brooklyn.

ALSO BY SIMON CRITCHLEY

On Heidegger's Being and Time

with Reiner Schrmann and Steven Levine

Infinitely Demanding:

Ethics of Commitment, Politics of Resistance

On the Human Condition

with Dominique Janicaud

Things Merely Are:

Philosophy in the Poetry of Wallace Stevens

On Humor

Continental Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction

Ethics-Politics-Subjectivity

Very Little, Almost Nothing

The Ethics of Deconstruction

If I were a maker of books, I would make a register, with comments, of various deaths. He who would teach men to die would teach them to live.

MONTAIGNE ,

That to Philosophize Is to Learn How to Die

CONTENTS

LAST WORDS

Creatureliness

INTRODUCTION

This book begins from a simple assumption: what defines human life in our corner of the planet at the present time is not just a fear of death, but an overwhelming terror of annihilation. This is a terror both of the inevitability of our demise with its future prospect of pain and possibly meaningless suffering, and the horror of what lies in the grave other than our body nailed into a box and lowered into the earth to become wormfood.

We are led, on the one hand, to deny the fact of death and to run headlong into the watery pleasures of forgetfulness, intoxication and the mindless accumulation of money and possessions. On the other hand, the terror of annihilation leads us blindly into a belief in the magical forms of salvation and promises of immortality offered by certain varieties of traditional religion and many New Age (and some rather older age) sophistries. What we seem to seek is either the transitory consolation of momentary oblivion or a miraculous redemption in the afterlife.

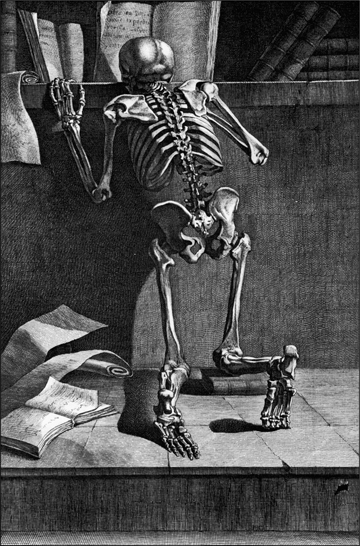

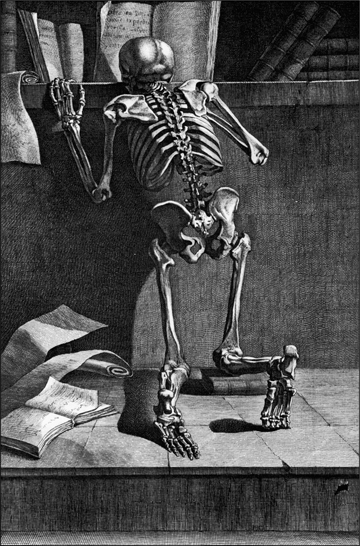

It is in stark contrast to our drunken desire for evasion and escape that the ideal of the philosophical death has such sobering power. As Cicero writes, and this sentiment was axiomatic for most ancient philosophy and echoes down the ages, To philosophize is to learn how to die. The main task of philosophy, in this view, is to prepare us for death, to provide a kind of training for death, the cultivation of an attitude towards our finitude that facesand faces downthe terror of annihilation without offering promises of an afterlife. Montaigne writes of the custom of the Egyptians who, during their elaborate feasts, caused a great image of death often a human skeletonto be brought into the banquet hall accompanied by a man who called out to them, Drink and be merry, for when you are dead you will be like this.

Montaigne derives the following moral from his Egyptian anecdote: So I have formed the habit of having death continually present, not merely in my imagination, but in my mouth.

To philosophize, then, is to learn to have death in your mouth, in the words you speak, the food you eat and the drink that you imbibe. It is in this way that we might begin to confront the terror of annihilation, for it is, finally, the fear of death that enslaves us and leads us towards either temporary oblivion or the longing for immortality. As Montaigne writes, He who has learned how to die has unlearned how to be a slave. This is an astonishing conclusion: the premeditation of death is nothing less than the forethinking of freedom. Seeking to escape death, then, is to remain unfree and run away from ourselves. The denial of death is self-hatred.

It was a commonplace in antiquity that philosophy provides the wisdom necessary to confront death. That is, the philosopher looks death in the face and has the strength to say that it is nothing. The original exemplar for such a philosophical death is Socrates, to whom I will return in detail below. In the

Next page