1. The TagoreGandhi Debate: An Account of the Central Issues

Abstract

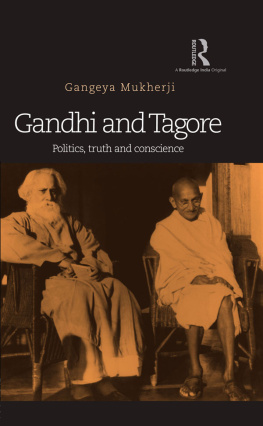

The TagoreGandhi debate was the second of the trilogy of the Gandhian debates with Savarkar, Tagore and Ambedkar. This chapter argues that engagement with criticism was fairly central to Gandhis life and thought. The chapter offers a detailed account of the major issues raised across the four phases of the exchange between Gandhi and Tagore. During this period (19151941), Tagore raised arguments against satyagraha , the non-cooperation movement, boycott of government schools, the burning of foreign cloth and Gandhis connection between spinning and swaraj .

There are times in life when the question of knowing one can think differently than one thinks, and perceive differently than one sees, is absolutely necessary if one is to go on looking and reflecting at all. (Foucault , p. 8).

To know that one can think differently than one does can be essential to sustain the acts of thinking and reflecting. One might ask why differences matter to ones being able to reflect on ones own. It is fairly comfortable to be in a world where everyone simply reaffirms what one thinks. Yet, the world seen and related by Lewis Carol in Alice in Wonderland could be fairly important to how one sees ones own world. Of course, difference is not always so easy to share or learn from as flights of fantasy. There are more difficult differences. Differences between people on how they perceive and understand things that matter to them. One can ask what could be good in being shaken out of the comfort of ones understanding of things by serious disagreement. An answer appears if one considers that without engaging with differences from ones own way of understanding reality one can never see things as they really are. For self, or largely ego-directed, visions of how one wants to see things could entirely encircle ones perceptions so as to make them progressively distanced from how things are as a matter of fact. Ones way of looking outward and reflecting on what one sees can gradually lose a sense of relation with thinking as an activity of the mind directed away from ones inner life and thereby different from introspection. A good way of ensuring that one remains open to the possibility that things can be substantially different from how one wants/thinks them to be is by engaging with difference. Debate as a mode of intellectual engagement can make significantly other ways of knowing things an inherent part of ones own way of thinking and knowing. It is interesting that debate was an important part of Gandhis life and thinking. In fact the GandhiTagore debate is only one of a trilogy of three significant debates in Gandhis life.

Gandhis first debate was with Savarkar . This debate possibly began in October 1906 when Gandhi and Haji Ojer Ally were in London on a second deputation from South Africa and were taken by Leius Ritch to stay at the India House. (At about this time Savarkar was a resident of India House.) In 1909, Gandhi was once again in London on a deputation from South Africa and met Savarkar (on 24 October 1909) at a dussera dinner in Bayswater at Nazimuddins Indian restaurant. The debate between Gandhi and Savarkar was about conflicting understandings of colonial Indias past, different interpretations of the present and contesting expectations of the future. It raised conflicting understandings of Indian identity, nationalism and Hinduism. Gandhis second debate was with Tagore and it started about the time they met in Santiniketan in March 1915. This debate was primarily about the nature of individual/collective freedom and the proper means to attain such freedom. Tagore raised several issues. To him it was important that an individual retain her freedom in the negotiation of relationships to imagined pasts, presents and futures. Such relationships could demand that the individual subsume her self-identity in the collective religious or national identity. For Tagore, collective identities were deeply problematic and a source of untruth. The third Gandhian debate was with Ambedkar in the 1920s. It was a debate about conflicting interpretations of caste and varna and of the proper means to eradicate untouchability and secure justice for the depressed classes.

In a sense all the three debates were about different issues: Indian identity/the collective self of India, freedom, and, questions of justice and Dalit identity. Yet, they can be interpreted as having shared an underlying tension. This can be spelt out as a tension about how the colonial Indian mind was to negotiate a relationship between tradition and modernity. What was common to the position of the three others in these debates was that (no matter their very different positions on tradition) they were comfortable with central ideas of Western modernity. While Savarkar was a revivalist and a supporter of tradition, he was not opposed to modernity. Savarkar made a significant distinction between specifically religious and the social-cultural aspects of the Indian/Hindu tradition. In his view, while it was necessary to reclaim the cultural and social identity of the individual or collective Indian self, the Hindu rashtra could be remodelled along the lines suggested by Western modernity. On this view, there was no antagonism between Indian/Hindu nationalism and the ways of life defined by the technological advancements of modern science. This argument perhaps made it possible for Savarkar to accept modern forms of political violence as the proper means for collective Indian freedom. Moving to the second Gandhian debate, Tagore reconstructed swaraj /freedom primarily (in terms fairly close to the Enlightenment and to Kant) as the individuals freedom to reason. Of the three others in the debates it was Tagore who emphasized the importance of a critical interrogation of the fundamental categories of modernity. Yet, Tagores intellectual affinity to the central ideas of the Enlightenment brought him fairly close to modern self-consciousness. The third interrogator, Ambedkar, was comfortable with the conceptual categories suggested by modernity. In his debate with Gandhi, Ambedkar used the language of majority/minority, federalism, democracy and rightscivil and socio-economic. In particular, Ambedkar chose not to turn to the Indian traditions for intellectual resources. In these, he located the powerful axis of subordination of the depressed classes. He recommended that any attempt for securing justice for the depressed classes ought to be disengaged from substantive appeals to the religious values of the Hindus.

The one significant difference between Gandhi and the three protagonists was that unlike his interrogators Gandhi did not share in the imagination of a future for India, which looked to modernity for categories to negotiate its new present.

It is significant that Gandhi came the closest to sharing conceptual space with Tagore. Though Tagore was not a traditionalist he retained a living relationship to Indias past through the Bengali language. Tagore and his family were an important part of the Bengali renaissance (which began around 1890 and ended in the 1940s). Furthermore, despite the intellectual affinity with the Enlightenment and its central ideas, Tagore could not be uncritically called a modern. He insisted on individual freedom in the mind while interrogating both tradition and modernity. In this connection, one can take note of his criticism of the modern Western nation state. Tagores relationship to (and understanding of) nature is also significant, for this put him at some intellectual distance from the anthropocentricism of modernity . It is hoped that this book (which is about the second of the three Gandhian debates) will be able to bring out the shared spaces between Gandhi and Tagore with some clarity.