Table of Contents

For

Denise Gurney Wheatcroft

1914-2007

Mutter, du machtest ihn klein, du warsts, die ihn anfing; dir war er neu, du beugtest ber die neuen

Augen die freundliche Welt und wehrtest der fremden.

Rainer Maria Rilke, Die dritte Elegie

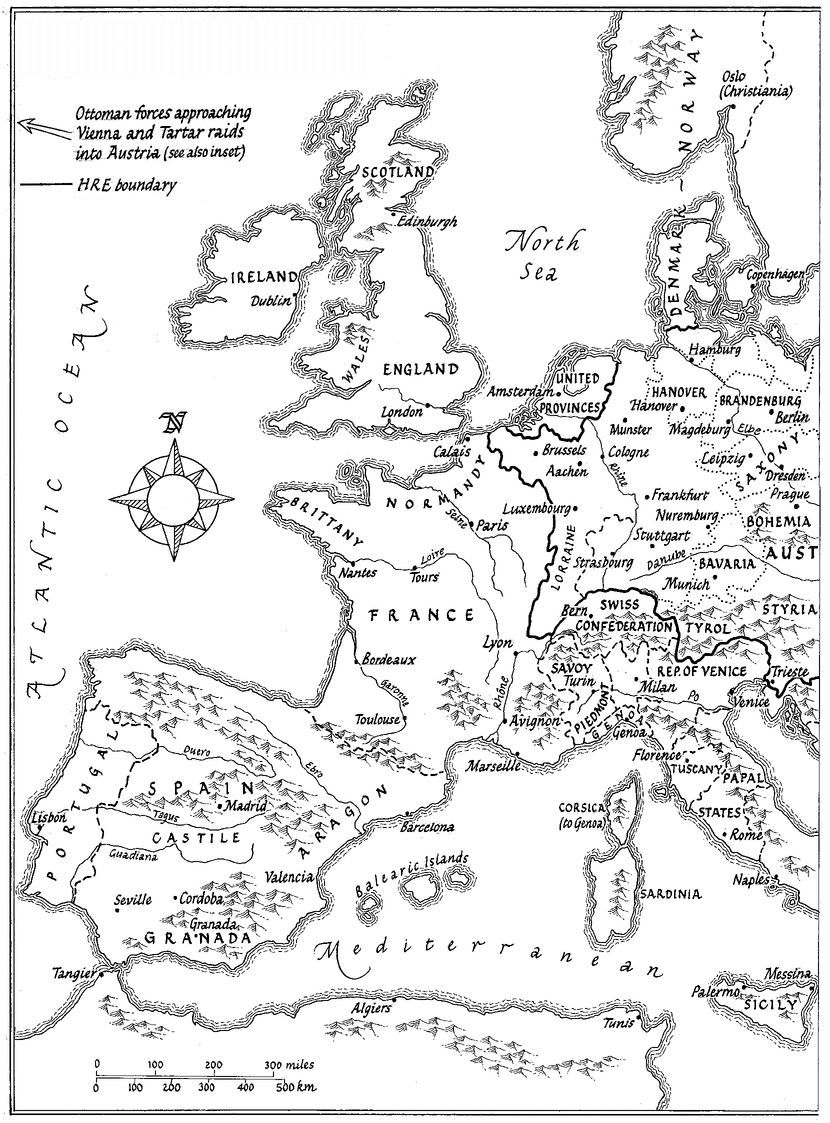

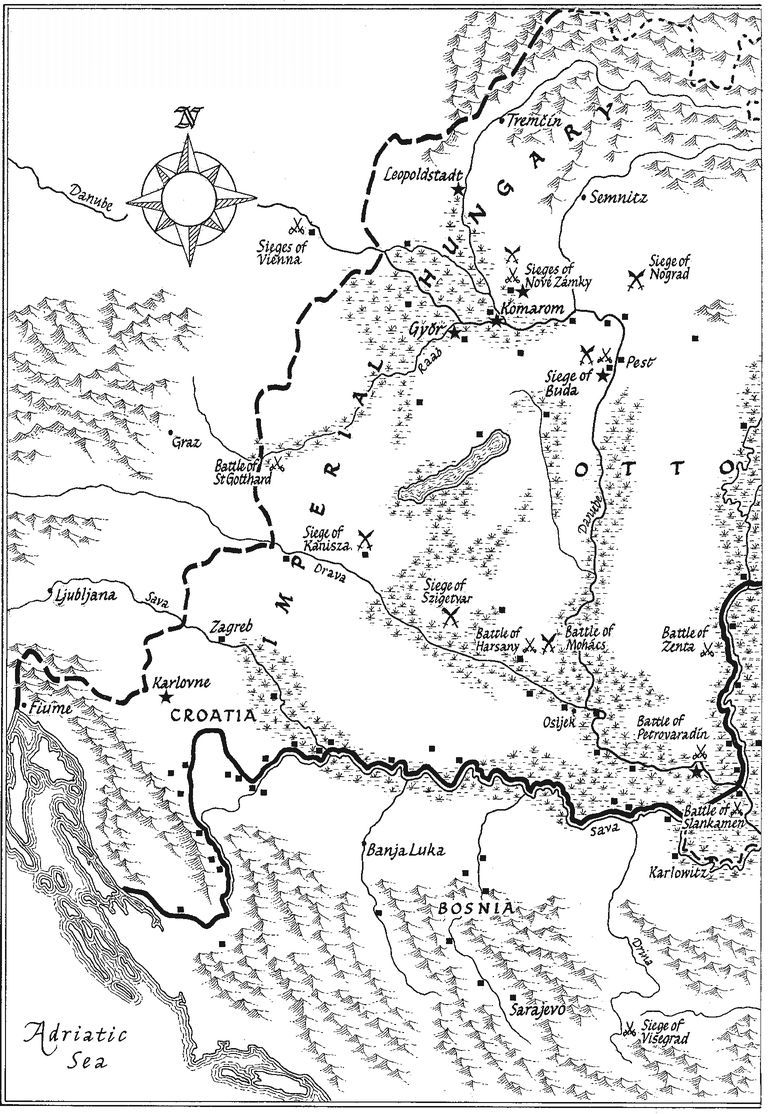

The Road to War, 1683

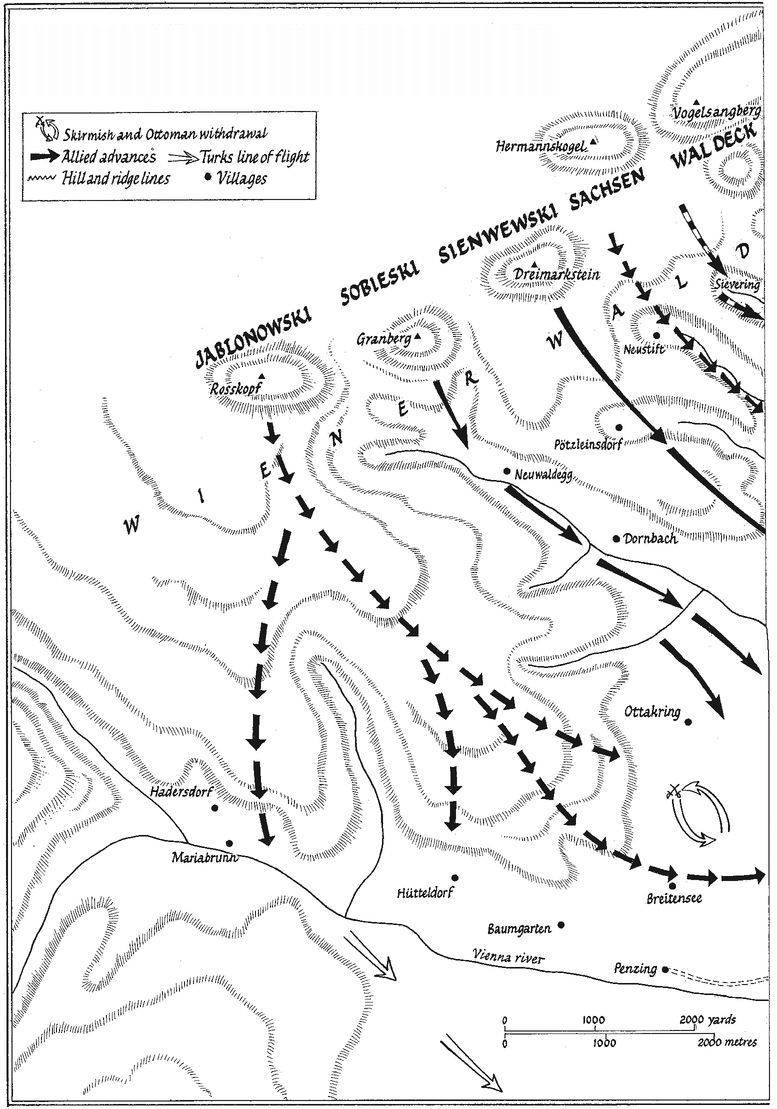

The Battle for Europe, 12 September 1683

The Zones of Conflict

Illustrations

For permission to reproduce illustrations author and publishers wish to thank the following: akg-images: 10 and 16; Belvedere, Vienna: 9; Bridgeman Art Library: 2, 11, 15 and 18; Magyar Nemzeti Galeria, Budapest/Tibor Mester: 1.

Acknowledgements

The Enemy at the Gate has been slowly growing for almost the entirety of my writing life. In a sense, the idea for this book began with one conference and ended with another. In 1972, Geoffrey Best and I organised a meeting at the University of Edinburgh in the then-new field of War, Peace and Peoples. We had both switched from other interests to the study of war and society; Geoffrey has gone on to be much more productive in the field than I have been: his friendship has been a constant in all the years since then.

In the late 1990s I picked up the threads of this subject which had been in abeyance over fifteen years. By then I had written other works on the Habsburgs and the Ottomans, and felt confident enough to take up the main questions which are the subject of this book: why did they fight each other for so long - and why did they finally stop fighting? In 2007 I had almost finished the text and then attended another conference, at the University of Reading, on Crossing the Divide: Continuity and Change in Late Medieval and Early Modern Warfare. Whereas at Edinburgh we had quite rapidly assembled a hand-picked group who met, talked and argued (sometimes fiercely) day and night for four days, Frank Tallett and David Trim had spent two years organising a much larger and more open meeting of experts: it was a huge success. The battlefield is not my preferred territory; descriptions of war and suffering can still cause me a very real sense of revulsion. Yet both Edinburgh in 1972 and Reading in 2007 demonstrated to me that war and conflict are central to our understanding of the past.

I want to thank those who have been both an inspiration and, like all good friends, a practical help. I have boldly dispensed with titles in listing them here.

John Keegan was in our Edinburgh group in 1972, and I have valued both his friendship and his work ever since. We have written books together and he was the first person to encourage my interest both in the Habsburgs and in the use of visual material in the study of history. For this book I have tried to apply some of the insights contained in his groundbreaking work, The Face of Battle.

John Brewer flits invisibly through these pages. He has been a trail-blazer in almost every topic that I have covered. The Sinews of Power showed the economic consequences of war in developed societies; and the huge collective work, Consumption and the World of Goods, edited with Roy Porter, provided the superstructure for my work on images and networks of communication. Now, with the final chapter of his book A Sentimental Murder: Love and Madness in the Eighteenth Century, John has again introduced me to ideas and material I would never have found for myself. Over the decades - in Florence, Los Angeles, Oxford and London - John and Stella have been the best of friends; neither of them can know how much their constant support has meant to me.

Writing this book has created a new passion for Hungary. I only wish that I could read and understand the marvellous sinewy language beyond a few words and phrases; my colleague Dana Kli has assured me that it is now too late to begin. I am very grateful for her help by translating material from the Hungarian, including a marvellously spirited version of the last section of Mikls Zrnyis epic Szigeti veszedelem (The Peril of Sziget), published in 1651 and never translated into English.

I now can entirely understand the old Latin tag extra Hungariam non est vita, si est vita non est ita - theres no life outside Hungary, and if there is, its not life. My guide in this discovery has been Stephen Plffy who, with the spirited support of Annamaria Almsy, has introduced me to the Hungarian way of life - from perfect food and wonderful wine to a sheer joy in life - and has provided often complex answers to my endless questions. I have benefited especially from Stephens extraordinarily broad knowledge of the issues and the personalities I encountered in the course of writing this book. Since Plffys have appeared for generations on these battlefields, this has been invaluable.

Budapest has become for me a quintessence of scholarly excellence. Thanks to Gbor goston in Washington D.C., who smoothed my path, I met Pl Fodor and the group of erudite and immensely active Ottomanists at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Terza Obrni in turn introduced me to Agnes Slgo Wojtila at the National Szchnyi Library, which houses the best researched collection of images I have encountered anywhere. Her kindness and expert knowledge have been a very great help. Opposite the Library, a Habsburg palace on the castle hill - the scene of so much bloodshed in this book - now contains the National Gallery of Art, a treasure house of nineteenth-century history paintings; next door to it, the City Museum is home to a huge collection of material on the siege of Buda in 1686. From their resources I have culled some of the paintings and images that appear in these pages.

Other parts of this book have been researched in Vienna, Graz, Edinburgh, London, Washington DC and Philadelphia. In Vienna, I consulted the Wien Bibliothek, the sterreichische National Bibliothek and the Wien Museum; in Graz, the Joanneum; in Great Britain, the British Museum, the London Library, Cambridge University Library and the National Library of Scotland; in Washington, the Library of Congress and the Folger Library. In Stockholm Henrik Andersson showed me the unique printers manuscript of Marsiglis last work in the collection of the Livrustkammeren; in Philadelphia, Earle Spamer helped me with the volumes of the Lindsay manuscripts held by the American Philosophical Society. I especially appreciated the kindness of Peter Parshall, who introduced me to the extraordinarily rich collection of engravings and woodcuts in the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.