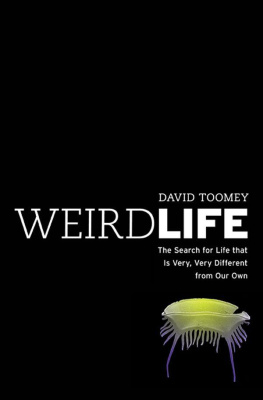

WEIRD LIFE

THE SEARCH FOR LIFE THAT IS VERY,

VERY DIFFERENT FROM OUR OWN

David Toomey

Contents

O ne of my favorite books as a child (and, truth be told, one of my favorites today) is Dr. Seusss If I Ran the Zoo . The I of the title is Gerald McGrew, a boy of perhaps age ten or twelve. The book opens as young McGrew visits his local zoo and finds its animalsa few sleepy-eyed bears and lionsuninspiring. He wishes for more exotic creatures, and so begins an extended daydream. Our youthful protagonist imagines himself as the zoos manager, releasing the bears and lions, which shamble off, one presumes, to find more stimulating environs. Then he fantasizes himself the zoos procurer, outfitted with pith helmet and butterfly net, in the heroic mold of Mallory and Burton, scaling mountains and crossing oceans in search of ever more exotic animals. And he finds them. In the Desert of Zind he captures a ferocious sort of camel called a Mulligatawny, and on the Island of Gwark he catches a gigantic bird called a Fizza-ma-Wizza-ma-Dill. And then he assures us that hes just warming up.

Young Gerald McGrew may be a fictional character in a childrens book, but his urges resonate. Humans, it seems, have always been less than satisfied with actual fauna, and so moved to invent alternatives. We all remember a few: the sphinx, the griffin, the basilisk, the phoenix. But ancient cultures created many more. Margaret Robinsons Fictitious Beasts (one of the most thorough and authoritative catalogues) lists several hundred, each description replete with details of behavior and in many cases an instructive encounter with a god or heroic mortal.1 To a biologist, what is striking about this imaginary bestiary, especially in comparison with the bestiary that nature actually has produced, is its paucity. The fact is that no one knows exactly how many species reside on our planet at present, but a conservative guess is 3.6 million, and some estimates are as high as 100 million.2 To those who prefer the real to the imaginary, it should come as good news that Robinsons work has a real-world cognate. The Encyclopedia of Life , an effort to build an online compendium of every extant species, is now at 500,000 web pages and growing.

Peruse Robinsons work at a rate of a second per page, and youll close the back cover after about four minutes. To get through the Encyclopedia of Life at the same rate youll need six weeks. Even then, youll have only a hint of the astonishing diversity of life over time. There have been at least 30 billion distinct species in the history of Earth.3 Suppose there were a book devoting a page to each species. To read it at a rate of a second per page, youd need nearly ten centuries.

Its not just the numbers. By comparison with reality, the creatures of myth suffer in another way. Most are little more than portmanteauswith, for instance, the head of one animal sewn onto the body of another. Any imaginatively sadistic schoolchild equipped with scissors and glue, you might think, could do as well. Even the parts list is severely scaled back, derived, as it is, almost entirely from the single branch of the tree of life that bears mammals, lizards, and birds. There are exceptions like Grandmother Spider, who figures in many Native American creation myths; and the kraken, the giant squid that inhabits the imaginations of coastal dwellers on several continents. And there are some rather wondrous hybrids. The vegetable lamb of Tartary ( Agnus scythicus or Planta Tartarica Barometz ), for instance, was a legendary plant of central Asia believed to grow sheep as its fruit. The sheep were connected to the plant by an umbilical cord, and when they had eaten all they could reach, the whole plant withered and died.4 But that is about as bizarre as the mythical beasts get. The overwhelming majority, if we were to classify them within standard taxonomies , would be vertebrates in the phylum Chordataessentially, animals with backbones.

For most of human history, anyone seeking a little strangeness in the proportion had to be satisfied with these. Then, in the mid-seventeenth century, natural philosophers discovered another bestiary, one that had two advantages over the imagined one. First, its animals were real. Second, they did not inhabit an exotic and distant country. In fact, they lived among us. And on us. A great many of them lived inside us.

By the late 1620s, the first of the type of instrument we call the microscope had been crafted and named. Half a century later, a twenty-eight-year-old British naturalist named Robert Hooke began to make his own, to use them to examine a great many things, and to sketch what he saw. Hookes work was not always easy. He had two sorts of microscopes. One, rather like the instrument we know, was a set of lenses fixed and aligned inside a small tube; the other, far more difficult to use, was a glass bead the size of a pinhead, held in a brass mounting. Of course, the subjects themselves could be uncooperative. The only way Hooke could immobilize ants without half crushing them was to get them drunk on brandy.

Despite such challenges, by 1664 Hooke had produced a work called Micrographia . Even now, in an age of high-definition television and IMAX 3D, it can be a startling experience to open the book to a folded page and gently pull its leaves apart to reveal, for instance, a copperplate engraving of a flea measuring a monstrous half meter across. One of Hookes contemporaries, Samuel Pepys, called the book the most ingenious he had ever read. Micrographia became a best seller, and many of its readers would have agreed with Hookes observation of the flea: the strength and beauty of this small creature, had it no other relation at all to man, would deserve a description.5 Still, a few criticized Hookes pursuit of knowledge with no obvious practical application, and many more were simply uninterested. The reason may have been that the animals discovered by Hooke and his successors were utterly unlike anything known at the time; they were perhaps too strange. Of course, there was another reason for the dis-interest: Hookes creatures were very, very small. Then, as now, humans equate small with unimportanta prejudice that, as we shall see, is as misguided as it is dangerous.

Some two centuries after Micrographia , natural philosophers discovered another bestiarythis one populated by animals that were as large by comparison with us as we are compared to house cats. They are long vanished from the Earth, but their appeal, perhaps especially to a certain demographic of seven-year-olds, has proved enduring. Some of the reasons are obvious. Dinosaurs are strange enough to inspire wonder, but not so strange as to be wholly unfamiliar. Tyrannosaurus r ex (a favorite of the aforementioned demographic) saw through eyes not unlike our own, breathed through nostrils, and walked over ground.

As the flea and Tyrannosaurus rex demonstrate, nature itself will outperform the uninformed imagination every time. If these creatures showed the limits of human imagination, they also enlarged it. With the discovery of microscopic and sub-microscopic life came questions about nourishment, reproduction, and mobility. Was there cooperation? How small was it possible for a living thing to be? The dinosaurs, likewise, produced new questions. How could such enormous masses be supported? How large was it possible for a living thing to be? And of course, why did they vanish?

Even as naturalists pondered these questions, there came a new understanding of life at fundamental levels. In 1859, Charles Darwin, prodded by the independent discoveries of British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection . Despite attacks by religious conservatives, the book was widely read (it would see six editions in Darwins lifetime), and within a decade several works were published in its support. In the early years of the twentieth century, biologists rediscovered Gregor Mendels laws of heredity, and American geneticist Walter Sutton found evidence that chromosomes carry units of inheritance. In the 1940s, Julian Huxley and George Gaylord Simpson consolidated natural selection and genetics, and DNA was found responsible for hereditary changes in bacteria. In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick published the structure of DNA in the journal Nature .

Next page