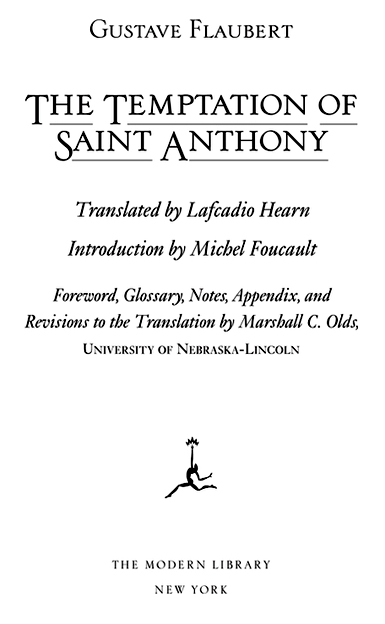

2001 Modern Library Paperback Edition

Biographical note copyright 1992 by Random House, Inc.

Foreword, glossary, notes, appendix, and revisions to translation 2001

by Random House, Inc.

Introduction translation copyright 1977 by Cornell University Press

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American

Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Modern Library, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada

by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

M ODERN L IBRARY and the TORCHBEARER Design are registered trademarks

of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Cornell University Press for permission to reprint material from Fantasia of the Library, by Michel Foucault, in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, edited by Donald F. Bouchard. Copyright 1977 by Cornell University. Used by permission of the publisher, Cornell University Press.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Flaubert, Gustave, 18211880.

[Tentation de saint Antoine. English]

The temptation of Saint Anthony / Gustave Flaubert; translated by Lafcadio Hearn; introduction by Michel Foucault; foreword, glossary, notes, appendix, and revisions to the translation by Marshall C. Olds.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-82413-4

1. Anthony, of Egypt, Saint, ca. 250355 or 6Fiction. 2. Christian saintsEgyptFiction. I. Hearn, Lafcadio, 18501904. II. Foucault, Michel. III. Olds, Marshall C. IV. Title.

PQ2246.T4 E5 2001

843.8dc21 2001044480

Modern Library website address:

www.modernlibrary.com

v3.1

C ONTENTS

F OREWORD

Marshall C. Olds

It is generally the practice, when offering a new edition of a classic literary work written in a foreign language, for publishing houses to present a newly translated text. After all, new translations with an ear for contemporary idiom are among the principal means by which such works can cross the combined gulfs of time and culture. Each generation deserves its own translation of Madame Bovary. Yet crossing those gulfs effortlessly and transparently does not always provide the recommended access to the work in question, particularly if there is a strangeness about it that was felt even by its first readers and in the original language. With that in mind, a different approach is being used for the present volume, and the reader of this new edition of Gustave Flauberts Temptation of Saint Anthony (1874) may be surprised to learn that the text here presented is, in fact, the oldest of the three translations of this work into English. Surprise should not entail alarm, however; justification for the decision is twofold. First and foremost, the translation begun by Lafcadio Hearn in 1875 or 1876 has an incomparable beauty and elegance that is a perfect match for the very particular language adopted by Flaubert in this, the most curious of his works. In the choice of an English Romantic idiom, a highly literary one at a remove from all other usage of the day, Hearn found the equivalent to the French of the Tentation de saint Antoine, a language markedly different from that of Flauberts own Realist novels. But there is more: Hearns translation not only matches the strangeness sensed by the reader of 1874, it has weathered so well that it communicates to the reader of English in 2001 the same distance communicated by Flauberts text to the contemporary reader of French. Unlike Madame Bovary, The Temptation of Saint Anthony cannot best be appreciated by being in some sense linguistically contemporary and so culturally relevant. It never was either, really, or at least not in any obvious way.

If Flaubert did not write his Temptation of Saint Anthony with modern life and language foremost in mind, this did not mean that the haunting work fell on deaf ears. To the contrary: A young generation comprised largely of poets and artists greeted the Temptation avidly. There have always been two readerships of Flauberts works (in fact, there still are), who, more often than not, are quite distinct. There are those readers who much prefer the contemporary realism of Madame Bovary and the Sentimental Education to the works that attempt to resurrect a distant past. Among the younger writers of Flauberts day who had this view were mile Zola and Guy de Maupassant, who would follow the path leading to Naturalism and psychological Realism. Then there were those who admitted to having a weakness for Salammb, the novel of ancient Carthage, and for the Temptation. It is revealing to see how many young poets, after the publication of the Temptation, wrote to Flaubert in respectful homage, sending copies of their work for him to notice. This was the generation that would bring forth Symbolism and the fin-de-sicle Decadent movement. Among these was the young Stphane Mallarm, who in 1876 sent Flaubert a copy of his poem The Afternoon of a Faun, printed on impossibly expensive paper with Manets engravings, and personalized To Gustave Flaubert, the Master. It was to the author of the Temptation that Mallarm wished to pay his respects, for having given to this generation, as Mallarm wrote in his preface to Vathek, a totally unique work blending epochs and races in a prodigious celebration of the literary imagination, and capturing the distinct scent of bouquins hors de mode, of old and rarely frequented books. There was no higher praise.

Only eight years younger than Mallarm, Lafcadio Hearn (18501904) may be thought of as the French poets contemporary in every sense but that of place. He was born Patricio Lafcadio Tessima Carlos Hearn, on the Greek island of Santa Maura (today Levks), which in ancient times was called Levkdhia, the source of his given name. His mother was Greek, and his father was a British army surgeon. Handed over for his education to a doubting and not especially wealthy aunt in Dublin, young Patrick was sent to school with the priesthood in mind, attending Irish and French Jesuit institutions. Doubtless to alleviate the torment of the strict and largely rote education he was receiving, he read voraciously in contemporary and ancient literatures, in mythology, and on all Oriental topics. A schoolyard accident cost him his left eye, and his right was said to have grown disproportionately large from overuse. He was rebellious, it seems, running away from school on at least one occasion. His aunt finally gave him up for lost and paid his passage to America in 1869, where he made his way to Cincinnati and found work as an assistant in the public library. He became a feature writer for the Cincinnati newspapers, and then continued journalistic work in New Orleans, where he moved in 1877. In 1887 Hearn began writing for Harpers magazine; postings took him to the West Indies and then, in 1890, to Japan, where he chose to remain for the rest of his life.

Hearn was drawn by nature to the peculiar and the exotic, and as a journalist, often wrote about violent crime and vice. In the United States at midcentury, these were topics that could only be handled by the newspapers, certainly not in magazines or novels, prompting Malcolm Cowleys observation that journalism was the Realism and Naturalism of American writers, and was the sole medium through which American writers could explore in their own way what writers in France were able to develop in more substantial literary forms. While living in New Orleans, and during his two-year stay in the West Indies, Hearn developed a passion for the French Creole people, their language and their literary and folk cultures. In Japan it was to be the same, and his voluminous writings of this period embrace all aspects of Japanese culture: social, religious, folkloric, historical, and literary. In Japan, Hearn finally married, to a woman of the Samurai class, and converted to Buddhism. He published much during his lifetime, beginning with translations of Thophile Gautier (One