INTRODUCTION

by Jacques Barzun

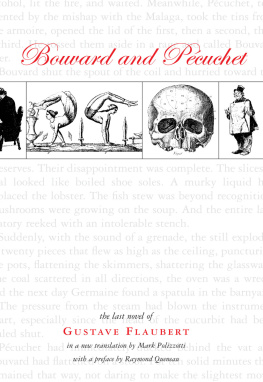

The Dictionary is of course known by reputation in England and America, better known perhaps than Bouvard itself; but despite some fragments rather carelessly translated in the magazine Gentry (Summer 1952), the little work cannot be said to have entered our literature as have Flauberts letters and novels.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the character of the Dictionary is frequently misunderstood, for it cannot be guessed at from mere description or random quotation. Indeed, the use and effect of the substance he has left us were probably not entirely clear to Flaubert himself. The Dictionary and the dialogue of Bouvard show many parallels, and Flaubert may have intended that after his two disappointed heroes have given up active endeavors and started copying again they should in factcollect and copy the materials of the Dictionary, together with the quotations of the so-called Album or anthology of absurdities. Both works exhibit specimens of the same conventional stupidity. But the alphabetful of definitions we have here is compiled from a mass of notes, duplicates and variants that were never even sorted, much less proportioned and polished by the author. We therefore do him an injustice in calling these flying sheets a work. More than one of them would very likely have been discarded as his intention grew clearer in the task of revision.

What is perfectly clear is Flauberts attitude towards the objects of his satire. We know his state of mind from Bouvard, from the letters, from innumerable anecdotes. Travelling by train during the time he was composing the novel, he was accosted by a stranger: Dont you come from So-and-so and arent you a traveller in oil? No, said Flaubert, in vinegar. From infancy, we are told, he refused to suffer fools gladly; he would note down the inanities uttered by an old lady who used to visit his parents, and by his twentieth year he already had in mind making a dictionary of such remarks. And of course, like nearly every French artist since the Romantic period, he loathed the bourgeois, whom he once for all defined as a being whose mode of feeling is low. From the early 1850s, Flaubert kept writing and talking to his friends about this handbook, this Dictionary, as his beloved work, his great contribution to moral realism. The project was for him charged with a personal emotion, not simply an intellectual one: To dissect, he wrote to George Sand, is a form of revenge.

Before its adaptation to the requirements of Bouvard, the separate Dictionary was to mystify as well as goad the ox: Such a book, with a good preface in which the motive would be stated to be the desire to bring the nation back to Tradition, Order and Sound Conventionsall this so phrased that the reader would not know whether or not his leg was being pulledsuch a book would certainly be unusual, even likely to succeed, because it would be entirely up to the minute (to Bouilhet, 4th September 1850). The same animus against the philistine public, which hardly lets up for an instant throughout Flauberts letters, was to find overt expression in the Dictionary, and with impunity: No law could attack me, though I should attack everything. It would be the justification of Whatever is is right. I should sacrifice the great men to all the nitwits, the martyrs to all the executioners, and do it in a style carried to the wildest pitchfireworks After reading the book, one would be afraid to talk, for fear of using one of the phrases in it (to Louise Colet, 17th December 1852).

All this may be called Theme I of the Dictionary: the castigation of the clich. This purpose was not new with Flaubert, though it arose in him from native impulse. The captions of Daumiers drawings, the sayings of M. Joseph Prudhomme in Henri Monniers fictional Memoirs of that character (1857), as well as a number of other less enduring works, testify to the nineteenth centurys growing awareness of mass production in word and thought. In the one year 1879, two contemporaries of Flauberts, the celebrated horn player and wit Eugne Vivier and the obscure LEpine, both published brochures having the same tendency as the projected Dictionary. Flaubert read them at once and was relieved: Nothing to fearasinine. In spite of this summary dismissal, Viviers Un peu de ce qui se dit tous les jours was quite superior to LEpines Parfait Causeur and it certainly anticipated the tone of the Flaubertian clich: They quarrel all day long, but really adore

The clich, as its name indicates, is the metal plate that clicks and reproduces the same image mechanically without end. This is what distinguishes it from an idiom or a proverb. The Dictionary of Clichs published some years ago by Mr. Eric Partridge straddles several species of set phrases and hence bears no likeness to Flauberts: it makes no point. The true nature of the thing Flaubert was out to capture and alphabetize was first discussed by an American in our century and endowed by him with a new name which has passed into the language: Gelett Burgesss Are you a Bromide? appeared as a magazine article in 1906. In book form it lists forty-eight genuine clichs (including the archetypal: It isnt the money, its the principle of the thing) and it makes the fundamental point that it is not merely because this remark is trite that it is bromidic; it is because with the Bromide the remark is inevitable.

In reading Flauberts Dictionary, this principle has to be borne in mind, for some of the utterances pilloried are manifestly true; they have to be said at certain times, being in themselves neither fatuous nor tautological. What damns them is the fact that they are the only thing ever said on the subject by the middling sensual man. As in the works of our modern lexicographerMr. Frank Sullivans Arbuthnot, the clich expertthe form, imagery and intention of the remarks are immediately recognized as approved, accepted, inescapable, reues before they begin. In Flauberts entourage these expressions recurred, more frequent and regular than the tides, and drove him frantic. For we should remember that he passed much of his life at Croisset, on the right bank of the Seine below Rouen, and was forced to listen there to much conversation that was not simply bourgeois and philistine, but invincibly repetitious and provincial. Traces of this aggravation are abundant in the Dictionary (e.g. C OFFEE , C OTTON , C LOTH ), and one may surmise that in the finished work these local allusions would have been either eliminated or signalized as home variants of cosmic bromidism.

At any rate, to Flaubert these repetitions proved more than signs of dullness, they were philosophic clues from which he inferred the transformation of the human being under machine capitalism. This he took as a personal affront. Representing Mind, he fought the encroachment of matter and mechanism into the empty places that should have been minds. He kept seeking ways of rendering what he saw, and in addition to Bouvard and the Dictionary, he got as far as writing and circulatingno one would produce ita sort of Expressionist play called The Castle of Hearts, of which the effect was to be comic and sinister. The chief scene would show, through the glass walls of identical houses along a Paris street, identical bourgeois families eating identical meals and exchanging identical words to identical gestures. This of course is akin to the scheme of Zolas