ULTIMATE QUESTIONS

Ultimate Questions

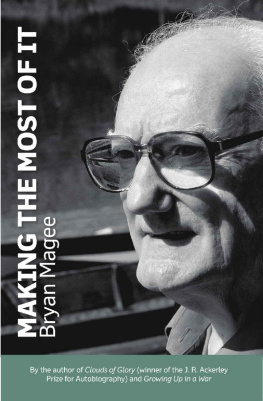

Bryan Magee

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2016 by Bryan Magee

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Magee, Bryan.

Ultimate questions / Bryan Magee.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-17065-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Human beings. 2. Philosophical anthropology. 3. Ontology. 4. Philosophy. I. Title.

BD450.M255 2016

128dc23

2015034960

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in ITC Galliard

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

ONE

Time and Space 1

TWO

Finding Our Bearings 17

THREE

The Human Predicament 33

FOUR

Can Experience Be Understood? 59

FIVE

Where Such Ideas Come From 69

SIX

Personal Reflections 87

SEVEN

Our Predicament Summarized 105

ULTIMATE QUESTIONS

ONE

Time and Space

WHAT WE CALL CIVILISATION HAS EXISTED FOR SOMEthing like six thousand years. We are accustomed to thinking of this as an exceedingly long time. Some of us have a vague outline of it in our heads. In my part of the world this usually starts with the Old Testament of the Bible, followed or accompanied by the rise of Greek civilisation, which was followed by the Roman Empireeach of which lasted for hundreds of years. Then came the thousand years of the Middle Ages. This ended with the Renaissance, which was followed by the Reformation, followed by the Enlightenment, then by the Industrial Revolution and the Romantic Eraand then on to the modern world and our own day. Across these same immensities of time other civilisationsunknown, or mostly unknown, to the people in my part of the worldrose and fell on other parts of the globes surface: China, Japan, India, Central Asia, the Middle East, South America, Mexico. We think of these vast historical changes as happening in only-just-moving timetime moving in the sort of way a glacier moves.

But now consider the following. There are always some human beings who live to be a hundred. More do so today than ever before, but there have always been some. I have known three quite well, two of them public figures: the politician Emmanuel Shinwell and the musical philanthropist Robert Mayer. (Robert knew Brahms, who was a friend of his family and stayed with them in Mannheim.) When Robert was born there must have been individuals who were then a hundred years old, whom a person could have met and got to know in the same way as I got to know him (or as he got to know Brahms, who died when Robert was seventeen). When those others were born, there must have been yet other such individuals. And so on: one could go further and further back, putting the lives of nameable human beings together, end to end, without any gaps in between. It comes as a shock to realise that the whole of civilisation has occurred within the successive lifetimes of sixty peoplewhich is the number of friends I squeeze into my living room when I have a drinks party. Twenty people take us back to Jesus, twenty-one to Julius Caesar. Even a paltry ten take us back before 1066 and the Norman Conquest. As for the Renaissance, it is only half a dozen people away.

When one measures history by a single possible human lifetime one realises that the whole of it has been almost incredibly short. This means that historical change has been almost incredibly fast. Each of those great empires that so imposingly rose, flourished and fell did so during the overlapping lives of a handful of individuals, usually fewer than half a dozen. So we ourselves are still near the beginning of the entire story. Tomorrow will be followed by the next day, next year by the year after, next century by the century after, next millennium by the millennium after, and the year 20,000 will inevitably come, as will the year 200,000, and the year 2,000,000. It is unstoppable. In fact, as periods in the existence of our planet and other bodies in the universe go, these are short periods of time. From now on, as long as there are human beings on this or any other heavenly body, humans will have a continuous, ever-extending history that traces itself back unbrokenly to our day now and our planet here. What is going to happen to all those peoplewhat will they doin unending time? How in the far, far future will they think of us now, who are so near the beginning of it all, and whom they will know a lot about if they choose to? How shall we appear to them in the light of all that will have happened between us and them, in a period many, many times as long as that between the dawn of civilisation and today?

I can imagine some of my readers throwing their hands up and protesting: How can we even think about these things? What concepts do we have for getting hold of any of this? Surely it is self-evident that, a mere two or three thousand years ago, geniuses as great as any there have been, people like Socrates and Plato, could not have foreseen todays world, or almost any of the worlds history between their time and ours? What imaginings can we hope to conjure up that are worth having about a period, all of it still in the future, so many times as long as that? Its a blank. We could make a few guesses about developments in the near future, perhaps, but history shows us that even those are more likely to be wrong than right. The truth is we dont know, we cannot know, we havent the remotest idea. We have no choice but to go on with our lives in the present, pushing into that tiny little bit of the future that our now slides into, without thinking about any of the things youre sayingnot because they arent worth thinking about (it would be wonderful if we could) but because we have no way of thinking about them, nothing to think about them with.

My answer is: I have posited nothing outside the ordinary, everyday order of eventsnothing religious, nothing supernatural, nothing transcendental. I have merely asked what will happen if circumstances continue exactly as they are today, and go on in this familiar way, as we expect them to do. For such a continuance not to occur might need the intervention of something supernatural, say, like time stopping. There is, it is true, a possibility that the earth will stop, because it could be smashed to pieces in a collision with a body from outer space, or frozen into lifelessness by the suns cooling; but such possibilities lie either millions (at least) of years in the future or at the outer extremes of unlikelihood. Most are such that the human race will get warning of them before they occur, and may even be able to do something to prevent their happening. For instance, nuclear weapons may turn out to be the saving of the human race. If astronomers tell us that a huge asteroid is on a collision course with our earth, we may be able to knock it off course with nuclear missiles and save ourselves. The missiles would have to be far more powerful than any we have now, but that will happen in the normal course of events. On the other hand it is possible that the human race will destroy itself with those same weapons, thereby bringing its history to an endbut that is rendered unlikely by the fact that our every movement from present into future is dominated by our need to solve the problems of survival. The most obvious likelihood is that the human race will go on living through vast stretches of future time but not necessarily on planet earth: people may find somewhere better to live, or be forced into moving by the earths becoming uninhabitable. In any case at every point in time they will have a past that is continuous with our past, most of which they will know better than we know it ourselves, because information technology will have been developing during that time.

Next page