Bryan Magee - Popper Cb

Here you can read online Bryan Magee - Popper Cb full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1973, publisher: TaylorFrancis, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Popper Cb

- Author:

- Publisher:TaylorFrancis

- Genre:

- Year:1973

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Popper Cb: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Popper Cb" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Popper Cb — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Popper Cb" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Modern Masters

| BECKETT | A. Alvarez |

| LAING | Edgar Z. Friedenberg |

| LUKACS | George Lichtheim |

| RUSSELL | A. J. Ayer |

| WEBER | Donald MacRae |

This edition published in 1974 by

FRANK CASS

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

by arrangement with Fontana

Transferred to Digital Printing 2006

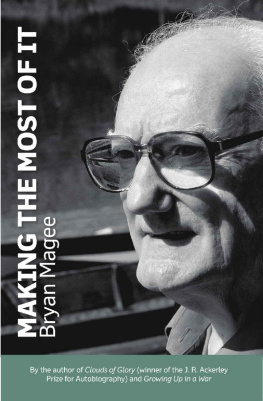

Copyright Bryan Magee 1973

ISBN 0 7130 0109 7

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publishers.

Cover photograph by Sir Ernst Gombrich

DOI: 10.4324/9780203041208

Short though it is, this book has benefited immeasurably from criticisms of an earlier draft given to me by Lord Boyle, Mr Tyrrell Burgess, Professor Ernest Gellner, Sir Ernst Gombrich, Mr David Miller, Professor John Watkins, Professor Bernard Williams and Sir Karl Popper.

to Ninian and Libushka with love

Man has created new worlds of language, of music, of poetry, of science; and the most important of these is the world of the moral demands, for equality, for freedom, and for helping the weak.

The Open Society and Its Enemies,

vol I, p.65

Introductory

DOI: 10.4324/9780203041208-1

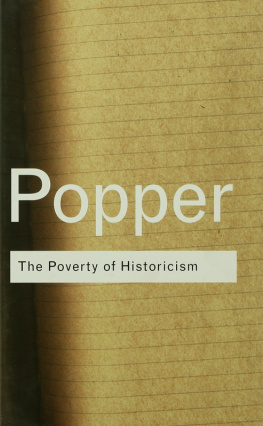

Karl Popper is not, as yet anyway, a household name among the educated, and this fact requires explanation. For as Isaiah Berlin writes in his biography of Karl Marx (third edition 1963), Poppers The Open Society and Its Enemies contains the most scrupulous and formidable criticism of the philosophical and historical doctrines of Marxism by any living writer; and if this judgment is anywhere near sound, Popper is in a world one third of whose inhabitants live under governments which call themselves Marxist a figure of world importance. But quite apart from this he is regarded by many as the greatest living philosopher of science indeed, Sir Peter Medawar, a winner of the Nobel Prize for Medicine, said on BBC Radio 3 on 28 July 1972: I think Popper is incomparably the greatest philosopher of science that has ever been. Other Nobel Prize winners who have publicly acknowledged his influence on their work include Jacques Monod and Sir John Eccles, who wrote in his book Facing Reality (1970): my scientific life owes so much to my conversion in 1945, if I may call it so, to Poppers teachings on the conduct of scientific investigations . I have endeavoured to follow Popper in the formulation and in the investigation of fundamental problems in neurobiology. Eccless advice to other scientists is to read and meditate upon Poppers writings on the philosophy of science and to adopt them as the basis of operation of ones scientific life. Nor is it only experimental scientists who take this view. The distinguished mathematician and theoretical astronomer, Sir Hermann Bondi, has stated simply: There is no more to science than its method, and there is no more to its method than Popper has said. The range of Poppers intellectual influence, unapproached by that of any English-speaking philosopher now living, extends from members of governments to art historians. In the Preface to Art and Illusion (described by Kenneth Clark as one of the most brilliant books on art criticism I have ever read) Sir Ernst Gombrich writes: I should be proud if Professor Poppers influence were to be felt everywhere in this book. And progressive Cabinet Ministers in both of the main British political parties, for instance Anthony Crosland and Sir Edward Boyle, have been influenced by Popper in the view they take of political activity.

These examples illustrate, straight away, some important things besides the extraordinary range of application of Poppers work. They show that unlike that of so many contemporary philosophers it has a notably practical effect on people who are influenced by it: it changes the way they do their own work, and in this and other respects changes their lives. It is, in short, a philosophy of action. Also, it has had such influence on many people who are themselves of first-rate distinction in their own fields. One could scarcely say, then, that Popper is neglected. This underlines all the more, though, the surprisingness of the fact that he is not better known many lesser thinkers are more famous. This is due partly to chance, partly to unintended misrepresentation of his work, and partly to an aspect of his method which facilitates misapprehension of it by those who have not studied it.

Karl Popper was born in Vienna in 1902. In his early and middle teens he was a Marxist, and then became an enthusiastic Social Democrat. Apart from his studies in science and philosophy he was interested not only in left-wing politics and in social work with children under the aegis of Adler, but also in the Society for Private Concerts founded by Schoenberg. For him, as for so many others, it was a thrilling time and place to be young. After his student days he earned his living as a secondary school teacher in mathematics and physics; but his chief absorptions continued to be social work, left-wing politics, music and of course philosophy, where he found himself, as he has tended to ever since, at variance with the fashion prevailing in his place and time, which for his generation there and then was the logical positivism of the Vienna Circle. Otto Neurath, a member of the Circle, nicknamed him the Official Opposition. This made him something of an odd man out. He found it impossible to get his early books published in the form in which he wrote them. His first book remains unpublished; and his first and seminal published work, Logik der Forschung (published in the autumn of 1934, dated 1935) was a savagely cut version of a book twice as long. It contains the chief of what have since become the generally accepted arguments against logical positivism.

Beneath the surface violence of the political scene in Vienna in the 1930s the lefts opposition to fascism was crumbling. Later, in The Open Society and Its Enemies (vol ii, pp. 164-165), Popper characterized the radical Marxist view as having been: Since the revolution was bound to come, fascism could only be one of the means of bringing it about; and this was more particularly so since the revolution was clearly long overdue. Russia had already had it in spite of its backward economic conditions. Only the vain hopes created by democracy were holding it back in the more advanced countries. Thus the destruction of democracy through the fascists could only promote the revolution by achieving the ultimate disillusionment of the workers in regard to democratic methods. With this, the radical wing of Marxism felt that it had discovered the "essence" and the "true historical role" of fascism. Fascism was, essentially, the last stand of the bourgeoisie. Accordingly, the Communists did not fight when the fascists seized power. (Nobody expected the Social Democrats to fight.) For the Communists were sure that the proletarian revolution was overdue and that the fascist interlude, necessary for its speeding up, could not last longer than a few months. Thus no action was required from the Communists. They were harmless. There was never a "communist danger" to the fascist conquest of power.

Included in the historical reality behind this passage were agonized debates about political strategy and morality in which Popper was involved, and which were the seedbed of much of his later political writing. He came to foresee, with depressing accuracy, the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, to be followed by a European war in which his native land would be on the wrong side; and he determined to leave before this happened. (This decision saved his life: for although his childhood had been a Protestant one, and both his parents had been baptized, Hitler would have categorized him as a Jew.) From 1937 to 1945 he taught philosophy at the University of New Zealand. In the earlier part of this period he virtually taught himself Greek in order to study the Greek philosophers, especially Plato. In the middle part he wrote, in English,

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Popper Cb»

Look at similar books to Popper Cb. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Popper Cb and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.