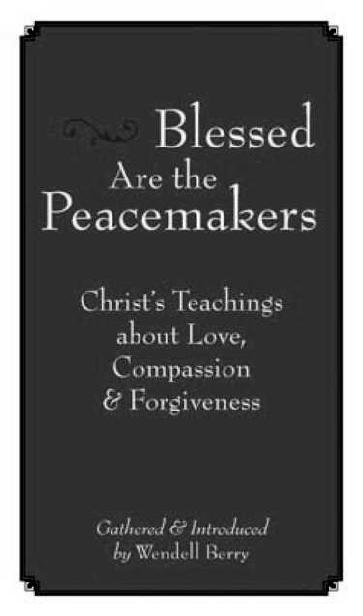

Blessed

Are the

Peacemakers

Blessed.

Are the

Peacemakers

Christ's Teachings

about Love,

Compassion

& Forgiveness

Gathered &Introduced

by Wendell Berry

Contents

Introduction

NY OBSERVER WOULD HAVE TO say that Christianity is fashionable at present in the United States. This might be a good thing, except that the observer, observing more closely, would have to conclude that, to the extent that Christianity is fashionable, it is loosely fashionable. It seems to have remarkably little to do with the things that Jesus Christ actually taught.

NY OBSERVER WOULD HAVE TO say that Christianity is fashionable at present in the United States. This might be a good thing, except that the observer, observing more closely, would have to conclude that, to the extent that Christianity is fashionable, it is loosely fashionable. It seems to have remarkably little to do with the things that Jesus Christ actually taught.

Especially among Christians in positions of great wealth and power, the idea of reading the Gospels and keeping Jesus's commandments as stated therein has been replaced by a curious process of logic. According to this process, people first declare themselves to be followers of Christ, and then they assume that whatever they say or do merits the adjective "Christian." (For don't we know that everybody named Rose smells like a rose?)

This process appears to have been dominant among Christian heads of state ever since Christianity became politically respectable. From this accommodation has proceeded a monstrous history of Christian violence. War after war has been prosecuted by bloodthirsty Christians, and to the profit of greedy Christians, as if Christ had never been born and the Gospels never written. I may have missed something, but I know of no Christian nation and no Christian leader from whose conduct the teachings of Christ could be inferred.

One cannot be aware both of the history of Christian war and of the contents of the Gospels without feeling that something is amiss. One may feel that, in the name of honesty, Christians ought either to quit fighting or quit calling themselves Christians. One way to see how far belligerent Christians have strayed from the words of Christ is to make a list, like the one presented in the following pages, of the Gospel passages in which Christ addresses explicitly the issues of human strife, forgiveness, compassion, and peacemaking.

The list that follows was made by me, with some help from friends. Other people's lists might differ somewhat, but I think they would be substantially the same. I have also included, in italics, the two passages that loose interpreters might interpret as justifying war: Matthew ro: 34-37 and Luke 2..z.: 3538. In both of these passages Christ is using the sword as a metaphor for the divisions He foresaw as results of His teaching and influence. If belligerent Christians wish to understand these passages literally, then they must explain why Christ speaks in the first passage only of "a" sword, and in the second of "two swords." He clearly was not raising an army. The many other passages gathered here deny the acceptability of the usual justifications for violence, official or otherwise.

The translation I have used is the King James Version, not only because of my love and respect for the language of that version, but also because it is the version that most English-speaking Christians have been reading for the last four hundred years while disobeying or ignoring Christ's commandments and praying for His help in their wars.

They have justified their disobedience on the grounds of the impracticality of obedience, though we have little proof of the practicality of disobedience, and precious few examples of obedience. The implication invariably has been that for a few feckless worshippers of God to obey Christ's commandments may be all right, but in practical matters such as war and preparation for war we will obey Caesar. The Christian followers of Caesar have thus committed themselves to an absurdity that they can neither resolve nor escape: the proposition that war can be made to serve peace; that you can make friends for love by hating and killing the enemies of love. This has never succeeded, and its failure is never acknowledged, which is a further absurdity.

The world's survival, so far, of this absurdity is explainable by the relative smallness, until recently, of the scale of war, and by the relative controllability, until now, of the most destructive weaponry. But now the scales of practicality have come to be differently weighted. The official terrorism of the Cold War and the doctrine of "mutual assured destruction" have already made us familiar with the ultimate absurdity: that we (or some other "we" equally devout and patriotic) may have to destroy the world in order to defend ourselves. To the surprise of some, no doubt, it is possible to look upon such an eventuality as impractical. To avoid it, we are going to need a better recourse than Caesar's. If we ever should become sane enough to reject total destruction as a means of victory, then, as my friend Wes Jackson once said to me, our evolutionary biologists will have to reckon how we could have received the best instruction for our survival two thousand years before it was most desperately needed.

Christ told us how to survive when He answered the question, Who is my neighbor? In the tenth chapter of Luke He tells the story of a Samaritan who cared for a Jew who had been badly wounded by thieves. As we know from the preceding chapter, in which the Disciples suggest in effect the firebombing of a Samaritan village, the Samaritans and the Jews were enemies. To modernize the story, then, and so to understand Christ's answer, we may substitute any other pair of enemies: fundamentalist Christian and fundamentalist Muslim, Palestinian and Israeli, captor and prisoner. The answer: Your neighbor is any sufferer who needs your help.

Matthew

NY OBSERVER WOULD HAVE TO say that Christianity is fashionable at present in the United States. This might be a good thing, except that the observer, observing more closely, would have to conclude that, to the extent that Christianity is fashionable, it is loosely fashionable. It seems to have remarkably little to do with the things that Jesus Christ actually taught.

NY OBSERVER WOULD HAVE TO say that Christianity is fashionable at present in the United States. This might be a good thing, except that the observer, observing more closely, would have to conclude that, to the extent that Christianity is fashionable, it is loosely fashionable. It seems to have remarkably little to do with the things that Jesus Christ actually taught.