Volume I

SAMAR HABIB,

Editor

Foreword by Parvez Sharma

PRAEGER

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

VOLUME I

ix

xv

xvii

Samar Habib

Walter L. Williams

Badruddin Khan

Jocelyn Sharlet

Tilo Beckers

Michael T. Luongo

Omer Shah

Max Kramer

Nur 'Adlina Maulod and Nurhaizatul jamila jamil

Barbara Zollner

VOLUME 2

Christopher Grant Kelly

Christopher Grant Kelly

Aleardo Zanghellini

Junaid Bin jahangir

Rusmir Music

Mahruq Fatima Khan

Ayisha A. Al-Sayyad

Ibrahim Abraham

Ilgin Yorukoglu

Ahmet Atay

Rabab Abdulhadi

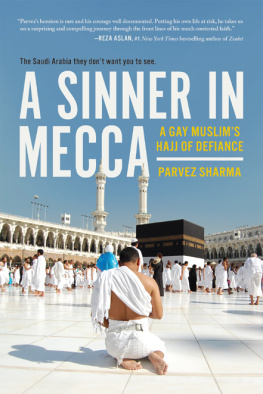

It is an honor to write the foreword for this excellent and thoughtful anthology that dares to visit some of the darkest corners of the taboo that permeates the consciousness of that unlikely creature: the gay or the lesbian Muslim, and certainly every other category that falls in the spectrum of sexuality as we understand it in much of the West.

I write with fierce urgency because I realize now more than ever that some of our most bitter battles in this new century will be fought on the frontlines of religion. The generations that follow us will deal with the consequences of rising extremisms in every faith. A very quick look into the fabric of America, the profoundly religious and moralistic society I live in, makes one realize that the gay marriage debate in this nation is fundamentally about the Church.

In making my documentary film, A Jihad for Love, I traveled to the very heart of Islam and reached a conclusion that perhaps is not immediately appealing to the readers of this book. In my lifetime I do not see Islam drafting a uniform edict saying that homosexuality is permissible, but then again, a ruling of that nature cannot be imagined as coming from the Vatican either. The case of Islam becomes further problematized because there is no one kind of Muslim. More than a billion Muslim people inhabit this planet, and, as A Jihad for Love proves, they inhabit geographical, linguistic, and cultural spaces that are enormously different. In fact, nothing in the religion can fall into the problematic monolith discussed most often in the independent media of Western societies. Sunni Islam in itself, being the religious denomination of the majority, has four major schools of thought: the Hanafi, the Hanbali, the Maliki and the Sha'afi, and they have never quite agreed on what to do with "the homosexual." The Shiites in Iran thrive on a culture of disagreement that permeates all of the corridors of learning that always lead up to the holy city of Qom.

As A Jihad for Love explains, the Quran, to some, is pretty specific about homosexuality, and debating contexts and semantics is un-Islamic. Many scholars within Islam have also argued that the very ijtihad or independent reasoning-that the gay Imam from South Africa, Muhsin Hendricks, brings up eloquently at the end of the film-is not an option because the doors to that were closed in the seventh century. Some who have agreed with the premise of the need for ijtihad have also said that the exercise is not available to every Muslim but only to the most learned alim in our ummah.

This note of pessimism, however, should be read more as a note of caution as we rush into seeking solutions that are merely theological. For our times, history has seemingly been divided into an easy before and after narrative following September 11. Much is made every day in the media and in the countless books produced since of the need for an Islamic Reformation. As I travelled to make the film, and then with its finished form, I realized that the process was ongoing and, if anything, the moment of Islamic reformation is now. We are living it. The question that comes with that knowledge is whether the "problem of homosexuality" is and even needs to be on the front burner for the many debates that Muslims need to have.

Having met more Imams and religious figures over the years than I can even count on my fingers, I realize a few things. Theological bickering can often be counterproductive, especially when one engages in questions of context and language and especially when the majority believes that the book itself is the literal word of God. Perhaps in that time of Jahilliyah, even our troubled and unlettered Prophet on hearing that first command, ikra, "recite" or "read" depending on whom you are talking to, did not comprehend the extent of the theological universe built with language in all of its contradictions and nuances. Clearly our Prophet did lay the foundations of an egalitarian system and perhaps he truly did create the firstever written constitution, the "Meccan Constitution," in the city formerly known as Yathrib. However, within that constitution and certainly in the seemingly rigid theology that would follow his lifetime, the language and the pronouncements were a product of the time. Our Prophet himself was a true man of his times. Islam, surprisingly, was laying forth a sexual and moral universe with rules and codes that had mostly been unavailable to the Jews, the Christians, and yes, the polytheists that inhabited Arabia 1,430 years ago. While I have always believed that a sexual revolution of immense proportions lay at the very heart of our religion's birth, much of the advances made in those times for creating a framework for human sexuality were limited within the institutions of heterosexual marriage, and because of this, and because of knowing the contexts now created for those who dare to re-engage with the Quran through the lens of modernity and the many academic discourses thus provided, I do not feel that a purely theological solution to what I have earlier referred to as the problem of the homosexual, is possible.

The theological debate that many within Islam have been engaged in for centuries often omits consideration of the impact religious rulings have on believers' lives. Theology and the rules that bind it often ignore the human experience and refer to homosexuality as an object, a behavior, a sin, without recognizing that sexual preference can be a major constituent of the religious self. As such, in A Jihad for Love, my approach was, rather than engaging in theological bickering, to show the very human dilemmas faced by these remarkable Muslims. Only in telling their stories are we able to get past the theological damnation that they suffer. We, and indeed our religious leaders in any of the monotheistic religions, need to realize that words in our holy books can and often do leap off the page and have a very real impact on people's lives. This is what I attempted to do in the film. I know, as a Muslim, that I am not supposed to "mess with the Quran," but as a believer and a defender of my faith, I also feel that, ideally, the ultimate relationship lies between the individual and his God. Clearly we do not and have not lived in an ideal world.