Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

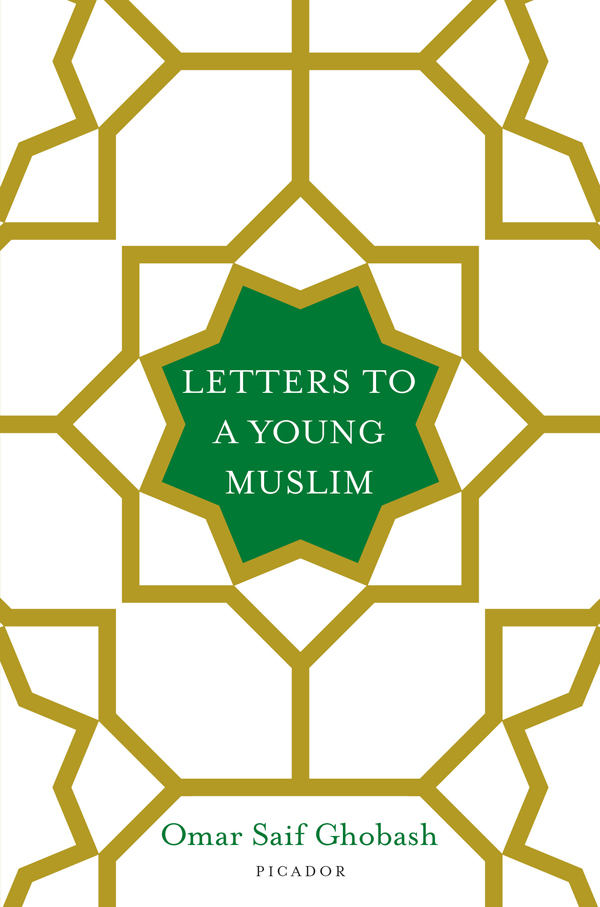

To my mother for all her patience, generosity, and sacrifice. And I promise my Abdullah a novel.

Out of respect for the Prophet Mohammed, it is customary to say the words peace be upon him or a variant of this phrase whenever he is mentioned. In print this is abbreviated to PBUH. Here, in the letters, I assume the reader utters it as appropriate.

I have two sons. My older son, Saif, was born in 2000 and my younger son, Abdullah, in 2004. Their presence in my life has provided me a framework for living. If I thought I had purpose as a bachelor, I discovered much greater purpose and meaning through my children, and with my wife. Whereas life as a bachelor meant looking out for myself, starting a family brought a sense of balance and responsibility that I could not have imagined. The responsibilities that come with building a family enable you to take a step back from yourself and see that the world consists of other people with greater claims on your energy and time than you yourself. Their existence provides the ground for my actions in the world. I feel an infinite obligation toward my children, who are still dependent on me and their mother for guidance and protection. I used to think that ideas and attitudes were something of interest but of no great importance. Matters would resolve themselves, things would work out. Now that I have children, I see the world through a broader lens. Now what happens in the world matters very much. And whose ideas dominate matters. In coming to this realization, I also recognized that the obligation of care and protection that I owe my children extends further. It extends more generally toward those of us who do not have the means to control their lives or who depend on others for the structure of our communities and societies.

I am the ambassador of the United Arab Emirates to Russia. The United Arab Emirates is located on the tip of the Arabian Peninsula, just south of Iran and east of Saudi Arabia. Our population was traditionally a mix of desert dwellers and seafaring pearl divers and goods traders. Today, we have a population approaching ten million, with over 180 nationalities represented. People live, work, and worship in peace alongside one another. I have been ambassador from January 2009 until today. I have had the privilege to be an observer of international relations from at least three very different perspectives. Because I speak English, Arabic, Russian, and French, and have friends and colleagues in the United States, Europe, Russia, and the Arab world, I have had access to the thinking that takes place within different cultures and political systems. The longer I perform my job, the more I am convinced of the power of ideas, and language, to move the world to a better place.

The world I grew up in was one where ideas floated around but had little connection with reality. I would hear about dreams of a new world order based on a very straightforward type of Islam. We were taught to pray and how to read the Quran. We were always told that certain actions were haram. Haram and halal are terms used to describe things that are prohibited (haram) or allowed (halal). Strangely though, most of the time we were told things were haramnot allowed. Eating pork and drinking alcohol seemed to fill people with horror. These were definitely haram. What else was haram? Lying and stealingor taking things that were not yourswere haram. Hurting others or yourself were also haramsince the body and life are gifts from Allah. Suicide in particular would send you straight to the fiery Hereafter, since this was taking what did not belong to you but rather to Allah. We were taken to the mosque on Fridays for the communal midday prayer. The sermons would be shouted out and people would stare into space until it was time for the short prayer. It was a pleasant feeling. You were surrounded by all types of people from laborers to millionaires. All lined up in orderly rows praying the same prayers and shaking hands with one another at the end of the ceremony.

Then there was what I would call fundamentalist Islam. What did this mean? It meant that the world would go back to what it was like at the height of the Islamic Empires of the seventh and eighth centuries. These ideas were repeated in school and after. The ideas always contrasted strongly with the world that surrounded us. This was a sense of their weakness in the world and their destruction at the hands of others. This was the time of the Lebanese civil war that began in 1975, and then the Iran-Iraq war, which lasted from 1980 to 1988. The return to the practices of our seventh- and eighth-century Muslim forefathers we were promised would bring us back the power, the glory, and the success that they enjoyed. There was another layer to the things we were taught. It did not always surface, but it was always there, I realize now. It was all the ideas that seemed to contradict earlier lessons. Ideas like suicide bombing. People would say that it was a great sacrifice to give your life for the community or the country or the Islamic Ummah, the global community of Muslims. My friends and I would ask how it was possible that committing suicide was seen as a great sin against Allah if done for reasons such as sadness, or unhappiness; and yet it was the greatest sacrifice a Muslim could make if it was done to fight the enemy? This question was relevant in the 1980s when I was a teenager, and is still relevant today.

Words in the air, until September 11, 2001. When the Twin Towers in New York were destroyed in the most shocking terrorist incident of my lifetime, I realized those words had now become a reality. The words that I had listened to and absorbed when I was a child had now taken on meaning in the world around me. These words were now creating a reality with consequences not just for Americans and Europeans but also for me and my fellow Muslims in the Arab world.

My first son was born in December 2000. I remember carrying him in a child sling on my chest in the summer of 2001as we visited Manhattan. A few days after we got back to Dubai, we witnessed the terrible events of 9/11 on CNN. I felt an overwhelming sense of responsibility toward this child. I decided that the time had come for me to take action in the limited ways that I could. I involved myself in the arts, in literature and education. My overwhelming desire was to open up areas of thought, language, and imagination in order to show myself and my fellow Muslims that our world has so much more to offer us than the limited fantasies of deeply unhappy people.

My work in diplomacy came later, and I have approached it with the same attitude of openness to ideas and possibilities. Through travel and interaction with all kinds of people, from the deeply religious to the highly knowledgeable, from the deeply uneducated to the hyperconnected, I see the common humanity that we all share. When I hear of different value systems and how they are going to clash, I see the values of human beings striving for a better life. I write these letters to both of my sons, and to all young Muslim men and women, with the intention of opening their eyes to some of the questions they are likely to face and the range of possible answers that exist for them. I want to show them that there are questions that have persisted from the first beginnings of human thought, and that there is no reason for the modern Muslim not to engage with them as generations before them did. I want to reaffirm the duty to think and question and engage constructively with the world. I want my sons and their generation of Muslims to understand that we live in a world full of difference and diversity.