Radical Skin,

Moderate Masks

Challenging Migration Studies

This provocative new series challenges the established field of migration studies to think beyond its policy-oriented frameworks and to engage with the complex and myriad forms in which the global migration regime is changing in the twenty-first century. It proposes to draw together studies that engage with the current transformation of the politics of migration, and the meaning of migrant, from the below of grassroots, local, transnational and multi-sited coalitions, projects and activisms. Attuned to the contemporary resurgence of migrant-led and migration-related movements, and anti-racist activism, the series builds on work carried out at the critical margins of migration studies to evaluate the border industrial complex and its fall-outs, build a decolonial perspective on global migration flows, and critically reassess the link between (im)migration, citizenship and belonging in the cross-border future.

Series Editors

Alana Lentin , Associate Professor in Cultural and Social Analysis at Western Sydney University

Gavan Titley , Senior Lecturer in Media Studies at the National University of Ireland , Maynooth

Titles in the Series

Radical Skin , Moderate Masks : De -radicalising the Muslim and Racism in Post -racial Societies , Yassir Morsi

Published by Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

www.rowmaninternational.com

Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd.is an affiliate of Rowman & Littlefield

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706, USA

With additional offices in Boulder, New York, Toronto (Canada), and Plymouth (UK)

www.rowman.com

Copyright 2017 Yassir Morsi

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-78348-911-4 (cloth)

ISBN 978 -1-78348-912-1 (paper)

ISBN 978 -1-78348-913-8 (electronic)

TMThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TMThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

My Lord, I ask you to expand my breast, make my task easy, undo the knot in my tongue so that my speech will become comprehensible.

Contents

On 9/11, following the second planes collision, and without much thought, I asked myself a rather worrying question. It has haunted me ever since. At the time, I knew little about politics, little about the Middle East or about al-Qaeda. No evidence as to who was responsible for the attacks had been provided, yet somehow, I knew of a responsible Other and I whispered to myself, what have we done?

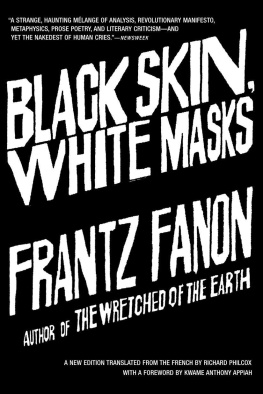

I suspect that I am an undisciplined and early scholar who lacks scholarly pace. Case in point, I will start by mentioning the wonderful Ashis Nandy and his brilliant work The Intimate Enemy. It greatly influenced me. And, I recall it fondly. But, I never closely read it and after the next paragraph or so, I will not bring it up again. Instead of dutifully giving a reading of Nandy's important arguments, as a better-paced scholar might, I will simply introduce a point and rush through to my next idea. I only mention his book because of what he provoked in me. For, this is my approach. I wish to trace the impacts of my experiences in reading scholarly work as much as recall the content of the work itself.

When I first read Nandy as a wide-eyed student, a most forceful point came to my realisation. And, my then crude attempt to talk back to empire began to take shape. This is why I remember his book. In Nandy I found an angle, a trajectory and a path. I found an opponent, and myself, and I awoke politically to gain a misgiving for the states of mind of the colonised, awoke to

I also mention this only because I wish to warn my studious reader that my books method (or lack of) is its haphazard style. Throughout my life as a Muslim of the West, I have too often appropriated works and (mis)read them to sound smart or play angry or figure things out as I go along. Such an approach has helped me with the arsenal of complexes that come with growing up as a person of colour. But, because of this wayward method, I am repeatedly, typically, left with a hazy incomplete recollection of things and what I wish to say. I only partly understand and reconstruct what an author like Nandy says. Yes, upon reflection, I have gained a dictionary of anti-colonial or anti-racist terms. And yes, I have an impression of the work's importance. But, I rarely achieve a clear or complete view of their thoughts. It has not only shaped the way I think, but how I have learnt to write. I guess this is the result of years of bad habits, and my impatience to fight the West.

I admit now that I pursued a tongue of fast-talking intellectualism. Words became my shield and concepts my weapon. So, I flipped quickly through pages and searched about for the aesthetics of a critical postcolonial scholarship to find myself a subjectivity, to fight racism, to be Muslim. I inherited what Nandy calls the the crudity and inanity of colonialism.

I found this rewarding until my subjectivity collapsed, that is, until I read Fanon.

This book resulted from exploring this collapse. It mixes partly read things with partly expressed Islams and partly recalled memories. It is written in the mood of a Dionysian drunkenness, which I will explain in more detail shortly. But for now I wish to put words to what I mean, and say the West is home and it is not; I hate it and love it, and hate to love it; I denounce the rhetoric of freedom in my pursuit of freedom. This dual and ambivalent aim too often imbalances me. Whether I am conscious or not, I read to write in ways where one part of me abrogates the other.

With all that said, I also believe a single aim binds my approach. My political habit is to make visible the (less than visible) centre of Western societys racialised power, to identify the traps of whiteness. I want to mention such debasing power, work through it, and to denounce the illusionary standards it demands from me. I want to explore the many ways I am compelled to be a good or bad Muslim.

I have come to dislike the neatness of the good Muslim, in thinking and talking about Islam and racism. I am repetitive and disorganized. I dislike the right angles of todays scholarship. I hate the performance of a balanced Islam. It is such a lie. The Muslim world is in turmoil and so am I. It is violent. It is regressive. It is burning and harmfully patriarchal and its beautiful and everything in between. It is in a sense to me partly known and a greatly unknown thing, and I must reject the therapeutic tones of a good Muslim who speaks to help ease (a very privileged) white anxiety and speak of it through common sense and a flow of premises. For the Dionysian thrown-ness that I will describe and have and inherited as a Muslim of the West deserves words beyond those of terrorist or radical or moderate or good. And, so I ramble to make sense of it all.

As a short summary, Nandy describes two types of colonialisms.

For the benefit of the readers, this somewhat messy auto-ethnography best start with its major point. In its easiest form, in a single (though vague) sentence, I propose that the Apollonian colonises half of Muslims today. By half, I mean conceptually not numerically. I mean the moderate of the moderate/radical binary. I use the Apollonian to mean the aesthetics of conversation that conceals colonialisms bloodied past. It stands for the beauty of bleach, of performing a talk about togetherness, of chatting about diversity, of loving tolerance, of right angles, of neatness and loyalties to nations. It comes from overlooking the concrete, Dionysian conditions of the Others coloured bodies and left-behind lives and the forgotten affects of such.

Next page

TMThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TMThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.