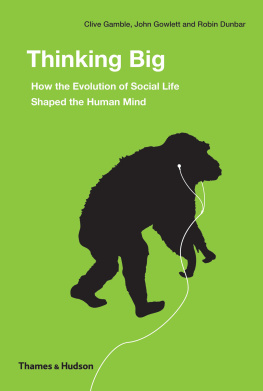

Thinking big is a very human thing to do. We have remarkable imaginations that take us back into the past and out into the future. We feast on films and literature and ruminate on the creativity of the human mind. We take innovations in social networking in our stride as we adapt to living in mega-cities. We work in global economies and access what we know of these big worlds from 24/7 news. But, for all this big thinking, we remain in some essentials small-minded. We have a cognition that equips each of us to deal best with small numbers of other people. While the size of our populations has grown exponentially, we remain, at core, the product of the small social worlds of our evolutionary history.

What we set out to explore in this book is the story of how our big-thinking social brain evolved. We do this by looking at ourselves and our closest living relatives the apes and monkeys as well as at the skulls and artifacts of our fossil ancestors. There is a link between the two and that is the size of the brain and the size of the small social communities they live in. We will examine the idea that it was our social lives that drove the growth of our most distinctive feature: the human brain.

Our ability to think big is part of our evolutionary story. It was with the desire to know more about this vital ingredient of being human that we undertook a seven-year project (20032010) funded by the British Academy as a celebration of its centenary. We called the project Lucy to Language: The Archaeology of the Social Brain and in the pages that follow you will learn much about Lucys journey from an ancestor with a small brain to a global species with an open mind.

The Lucy project was collaborative and interdisciplinary. Its rationale was underpinned by Sir Adam Roberts, President of the British Academy, when he wrote about the public value of the humanities and social sciences as follows: The humanities explore what it means to be human: the words, ideas, narratives and the art and artifacts that help us make sense of our lives and the world we live in; how we have created it, and are created by it. The social sciences seek to explore, through observation and reflection, the processes that govern the behaviour of individuals and groups. Together, they help us to understand ourselves, our society and our place in the world. This sums up the intent of our Lucy project to explore the past and the present to provide a fuller account of where we have come from and why we act the way we do.

Our greatest thanks go to the British Academy and their decision to fund a project that drew together the humanities and the social sciences. We were also extremely fortunate in having a Steering Committee of Garry Runciman, Wendy James and Ken Emond, who read all our reports, attended all our conferences and through their enthusiastic support and advice added immeasurably to the success of the research undertaken. We would also like to thank David Phillipson FBA for all his help in furthering our research in Africa.

We benefited throughout from the encouragement and wise advice of the projects Honorary Fellows: Leslie Aiello, Holly Arrow, Filippo Aureli, Larry Barham, Alan Barnard, Robin Crompton, William Davies, Bob Layton, Yvonne Marshall, John McNabb, Jessica Pearson, Susanne Shultz, Anthony Sinclair, James Steele, Mark van Vugt, Anna Wallette, Victoria Winton and Sonia Zakrzewski.

One of our goals was to build the next generation of researchers in human evolution to work across the humanities and social sciences. We were very fortunate in having such a talented group of postdocs and postgrads, many of whom are now embedded in the universities of the world. Our postdoctoral research fellows were Quentin Atkinson, Max Burton, Margaret Clegg, Fiona Coward, Oliver Curry, Matt Grove, Jane Hallos, Mandy Korstjens, Julia Lehmann, Stephen Lycett, Anna Machin, Sam Roberts and Natalie Uomini; our research assistants were Anna Frangou and Peter Morgan; and our postgraduate students were Katherine Andrews, Isabel Behncke, Caroline Bettridge, Peter Bond, Vicky Brant, Lisa Cashmore, James Cole, Richard Davies, Hannah Fluck, Babis Garefalakis, Iris Glaesslein, Charlie Hardy, Wendy Iredale, Minna Lyons, Marc Mehu, Dora Moutsiou, Emma Nelson, Adam Newton, Kit Opie, Ellie Pearce, Phil Purslow, Yvan Russell and Andy Shuttleworth. In relation to African research and fire studies John Gowlett also thanks especially Stephen Rucina, Isaya Onjala, Sally Hoare, Andy Herries, James Brink, Maura Butler, Laura Basell, National Museums of Kenya and NCST Kenya; also Nick Debenham, Richard Preece, David Bridgland, Simon Lewis, Simon Parfitt, Jack Harris, Richard Wrangham and Naama Goren-Inbar.

Funding for the fellowships and studentships came principally from the British Academy Centenary Project, and our meetings, fieldwork and study leave were made possible by grants administered under the British Academys Research Professorship, Small Grants, Conference and Exchange funding programmes. We were also very grateful for additional funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Natural Environment Research Council, the Leverhulme Trust, the Boise Fund and the EU-FP6 and FP7 programmes. We also received generous support from our host institutions, Oxford University, Liverpool University, Royal Holloway and Southampton University.

Any long-running project is marked by the natural rhythms of life. Five babies were born and none of them are called Lucy! We are happy to say their social brains are developing nicely.

Clive Gamble

John Gowlett

Robin Dunbar

The history of human evolution is an iconic story that never ceases to mesmerize and enthral. Buried in our past is one of the triumphs of evolution, the story of how a common-or-garden African ape began to change both its body form and the way it lived its life and how in doing so, it eventually became the dominant species on earth. It is only within the last century that we have really come to appreciate the grandeur of this story and the moments of uncertainty and near-extinction that threatened it.

From small beginnings

Some 7 million years separate us from the time that the ancestors of humans and chimpanzees were a single species: a small, undistinguished African Miocene ape. We finished that part of our story in the last 5000 years as the only animal to have settled all the terrestrial habitats of the earth, from the tropical forest to the arctic tundra and from high mountain plateaux to small islands in the remotest oceans. During that long history the size of our brains trebled and our technology progressed from simple stone tools to digital marvels. We walked upright, spoke, made art in profusion and crafted worlds of enormous imaginative complexity in the name of religion, politics and society. Truly, we are no longer apes.

For most of these 7 million years we were not alone. Where our remote ancestors lived they often shared the space with other closely related species. This ancient pattern began to change within the last 100,000 years when people like us, modern humans, moved out of Africa and through the Old World. Older species like the Neanderthals of Europe and Western Asia were displaced and became extinct. These same modern people also passed beyond the boundaries of the Old World, peopling for the first time Australia and the Americas. By the time the last Ice Age ended 11,000 years ago, we were the only species in town; Homo sapiens was now alone, in an evolutionary sense.

Soon we also became a global species. The move to farming led in one direction to cities, civilizations and a massive increase in population. And in another direction the domestication of plants provisioned the voyages into the remote Pacific, beginning 5000 years ago, while harnessing the power of animals made it possible to traverse cold and hot deserts. No wonder then that the European voyages of discovery found people everywhere; what is more, these explorers tested time-and-again the historical circumstance of

Next page