Robin Dunbar - The Human Story

Here you can read online Robin Dunbar - The Human Story full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Human Story

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Human Story: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Human Story" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Human Story — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Human Story" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For Steve

who set me on my way

Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery,

None but ourselves can free our mind

Bob Marley, Redemption Song (1980)

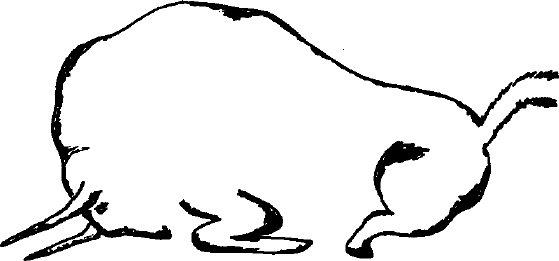

The light from the tallow lamp flickered uncertainly in a draught,breaking the mans concentration. He stood back for a moment tosurvey his handiwork. He picked up the carved stone bowl thatserved as a lamp and held it up to the rock wall, the better to seewhere he had been working. Around him on the wall, images ofanimals seemed to move, magically brought to life by the gutteringtallow wick. A great jumble of bison, deer, and horses cascadedthrough a timeless space. Here, one seemed caught in a moment ofsurprise; there a bison rested on its haunches with its head turnedas though to survey the unwarranted intrusion into its thoughts asit lay quietly chewing the cud.

He set to work again, his brow puckered in concentration, carefullydrawing in the outlines of a new animal with a piece of charcoal.Warmed by the fire of his imagination, he was oblivious ofthe coldness of the cave around him. In his minds eye, he sawwhat he had to draw, a vision of a world as real and tangible as thestone on which he worked a place where animals gambolledthrough woodlands or grazed in grassy glades, sunlight dapplingtheir shoulders. He worked with all the skill he could muster,intent on capturing the vision in his mind before it vanished.

He had spent years of his life perfecting these skills, coming backto this cave every spring, when the land was bursting with newlife, to create his own imaginary life here on the rock walls. Sometimes,he came alone; sometimes, with others. But always with thesame goal: to undertake the journeys, and then to make an enduringrecord of his travels, to capture the sights he saw, the wrenchingemotions he felt as he sped through dark and often dangerousplaces journeys whose end he could never quite foretell.

He always knew when that moment had arrived, though hecould not always anticipate it, for it was as elusive as the deer thathe hunted in the woods. Even though he had set out on the journeymany times, the great mystery was that the path alwaysseemed to be different. Only the end, when it came, was the same,bringing that sense of arrival at a familiar place, that feeling ofrelief tinged with exhaustion from a difficult road travelled, ofdangers that had been safely negotiated once more.

And now, as after every journey, he came back to the cave torecord his experiences and what he had seen. The bisons form onwhich he was working gradually took shape the way he had seen itso close up that, when it had turned its great head towards himand fixed him languidly with one eye, it was as though he waspeering into its mind through that great liquid portal. Now, its eyegazed back at him from the wall, fixing him once again with itsglassy stare. In his mind, he could recreate that moment of surprise,of fear, that always accompanied the uncertainty when hecould not be sure what the great beast would do. Sometimes, byturning away to the darkness of the cave and then turning suddenlyback again or by coming unexpectedly upon some earlierpainting that he had forgotten about he could sense once morethat same tension just for a fleeting moment.

So engrossed was he in his work that several hours passed withouthis noticing. But eventually, the tiredness in his arms and thegrowing pangs of hunger persuaded him to put down his drawingmaterials and set off down the long winding passage back to themouth of the cave. He emerged into the harsh light of late afternoonfrom the caves mouth. The entrance was quite deceptive,being hidden behind a jumble of boulders and beech trees. It gaveno clue to the size of the cave behind the long winding tunnelsthat you sometimes had to crawl along on your belly, the vaultedchambers that seemed to occur with no plan along the tunnel itselfor opened off as blind side-chambers.

He glanced at the sun hanging above the western horizon andsaw that it was already late afternoon. He blew out the wick in thetallow lamp and placed it in a small niche in the rock wall justinside the entrance. And, feeling content with his days work, setoff down through the trees to where their camp nestled beside theriver in the valley bottom a few miles downstream

*

One hundred and eighty centuries later, in 1879, Maria, the young daughter of Don Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, idly glanced up towards the cave ceiling above her head while her father busied himself beside her, searching the floor for prehistoric artefacts. What she saw in the faint glow of the oil lamp that her father had placed beside him made her reach involuntarily to grab onto his coat-tail: looming down at her out of the gloom, bison and horses were pouring out of the rock. Disturbed from his searches, Don Marcelino turned irritably to remonstrate with the child. But her up-turned face her eyes fixed on something above him, her mouth wordlessly opening and closing at once made him realise that there was something unusual. He looked slowly up above him, his eyes searching the gloom. He reached for the oil lamp and held it above his head so that he could see better and let out a gasp. Above him, the bison, deer and horses turned and twisted, bunched up against each other, fighting for space, or lay chewing the cud, just as they had been left 18,000 years ago by the painters who had made them.

For Don Marcelino, this was a discovery beyond compare. Excited and impressed by the carved statuettes and ivory plaques that had been found in the recently discovered prehistoric caves in nearby southern France, he had spent several years searching the caves near Santander in northern Spain in the hope of discovering his own treasure trove of prehistoric art. His efforts had proved fruitless. And now, his searches in the cave at Altamira had accidentally led him to the discovery of some extraordinarily spectacular prehistoric paintings. His reputation was surely made. The rich and the famous, the scholars and the antiquarians, would flock to his cave and he would be fted at all the great scientific gatherings for years to come.

Don Marcelino was to die a disappointed man. After an initial flurry of interest, the antiquarians of the day declared the paintings too advanced to be the work of primitive man. Rather, they must have been painted by someone who had visited the cave in recent years perhaps Don Marcelino himself. Though they never quite accused him of forgery to his face, the sniff of it seemed to be there in the fetid air of the Altamira cave. Don Marcelino withdrew to his family estate. He died, a frustrated and embittered man, just nine years later. It was not until 1902 that the paintings were accepted as being of genuine prehistoric age. More extensive explorations had eventually revealed that the cave had gallery after gallery of paintings, sketches and drawings running more than 200 metres into the hillside. But by then, Don Marcelino had been in his grave the better part of twenty years, and his grown-up daughter had other things to distract her from the paintings that had so startled her as a child that summer morning.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Human Story»

Look at similar books to The Human Story. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Human Story and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.