THE BRAIN

Big Bangs, Behaviors, and Beliefs

Rob DeSalle & Ian Tattersall

Illustrated by Patricia J. Wynne

Published with assistance from the Louis Stern Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2012 by Rob DeSalle and Ian Tattersall.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (US office) or sales@ yaleup.co.uk (UK office).

Designed by Lindsey Voskowsky.

Set in Joanna MT type by Westchester Book Group.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

DeSalle, Rob.

The brain : big bangs, behaviors, and beliefs/Rob DeSalle and Ian Tattersall;

illustrated by Patricia J. Wynne.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-1 7522-6 (clothbound: alk. paper) 1. Cognition.

2. Neurophysiology. 3. BrainEvolution. I. Tattersall, Ian. II. Title.

BF311.D466 2012

612.82dc23 2011044329

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Erin, Jeanne, and Maceo

CONTENTS

PREFACE

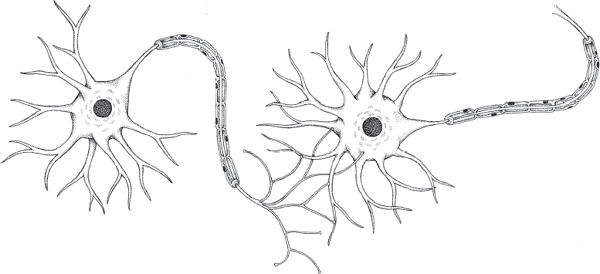

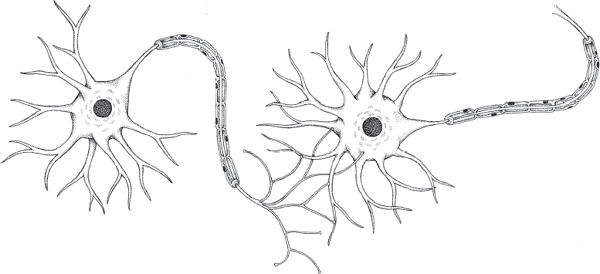

You dont have to peer expensively out into the farthest reaches of the cosmos to encounter the deepest mystery in the universe. Look no further than right between your own two ears. The human mind is nowhere challenged as much as by the endeavor to understand the workings of the brain that produces it. Yet despite huge practical difficulties, the effort to comprehend how brain produces mind is perhaps more intrinsically fascinating than any other quest in science. The many other organs that make up our bodies can be pretty well understood as machines, devoted to fairly clearly defined, if complex, functions. The special challenge posed by the brain-machine is that within it there also resides a ghost: our emergent consciousness, the properties of which far exceed the sum of the internal connections and electrochemical discharges that give rise to it.

The same is also true, at least to some extent, for the brain of every other creature that possesses one: after all, each has a consciousness of some kind, if only the rudimentary ability to distinguish between self and other. But there is nonetheless something very special about the human brain. As far as we can tell, it is alone in its ability not only to respond to the stimuli that come in from the world around it but also to literally remake that world in imagination. Nobody knows exactly how it accomplishes this trick, but a huge amount is already understood, not only about its structure and functioning but about the wider zoological and evolutionary contexts in which the amazing modern human brain and its unique properties need to be comprehended. These are the subjects of this book and of the American Museum of Natural History exhibition (Brain: The Inside Story) that inspired it.

In their structure our brains bear the marks of a long and tortuous ancestry. These odd machines are something that no human engineer would ever have designed; and if we understood nothing of their complex and accretionary half-billion-year history we would be at a loss to explain their apparent untidiness. We need, then, to analyze them in evolutionary terms. But if an evolutionary approach to understanding the human brain is to make even a little sense, we also need to know where we fit into the larger scheme of life. This is because the living world around us, together with the ways in which it is organized, offers a host of clues to how we achieved our unusual intellectual eminence. Yet even the combination of knowing both our place in nature and how we got there is not quite enough. We need also to understand the underlying evolutionary mechanisms.

Most of us were taught in school if indeed the subject was even mentioned hat evolution basically involves steady improvement over the eons. But it has become widely appreciated, within our own academic lifetimes, that there is a lot more to evolution than this. And once we realize that evolution is not always the fine-tuning mechanism many of us thought it was, we can begin to appreciate more fully the facts of our biological history as human beings.

These basic facts are provided by our fossil record, the preserved physical remains of our predecessors. Among other things, fossils show how the human brain has dramatically expanded in size over the past two million years or so. And, almost uniquely in the human case, there is more. Because, for the past two and a half million years or more that have elapsed since the invention of stone tools, we also have the archaeological record, the direct register of the behaviors of our hominid predecessors. By comparing our physical and behavioral records we can better understand past patterns of innovation in human evolution, and we can begin to reconstruct the framework within which the extraordinary human spirit emerged.

Still, we cannot do this without first understanding the other kinds of brains that exist on earth and indeed, appreciating how it is that some living things get by perfectly well without any brains at all. And we also need to know how our brain works today. Exactly how our unique human consciousness is generated remains for the time being a mystery. But a huge amount is already understood about brain processes at the molecular, anatomical, and functional levels; and new techniques of imaging have given us unparalleled insights into our brains at work. These technologies allow us to see in real time what actually goes on in human brains when they are subjected to specific stimuli or are set to performing particular tasks. We have also developed an advanced appreciation of the layered structure of the brain and of how this relates to the increasingly complex functions that vertebrate brains have acquired over the eons.

In this book we will look at all of the factors that led to our ability to think about thinking, and we will see just how unique our modern way of processing mental information is. Thanks to some remarkable new developments, we will gain insight into the true complexity (and murkiness) of the decision-making processes that go on in our brains, and we will look at how the untidiness (and creativity) of our mental processes results from the long and eventful evolutionary history of the brain. We will see how the qualities of our minds that we prize the most are emergent, rather than the fine-tuned products of inexorable natural selection.

We will also look toward the future of our brains. We are the recently arrived and sole hominid inheritors of the earth. Yet in our short tenure we have made a more profound impact on the planet than any other species has ever contrived to do. Most of the negative effects of human activity are by-products: the unintended consequences of a reckless attitude. Can we expect evolution to burnish us into better stewards of our environment? Can we hope for genetic engineering to make us more responsible, or more efficient, or simply better? Or are we going to have to learn to live with ourselves as we are? We hope to show that we are capable of understanding these important questions as long as we keep them in evolutionary context; and we may, indeed, even be capable of dealing with the consequences of our activities as long as we recognize and compensate for the untidiness of our thought processes.

Next page