Diarmaid MacCulloch

All Things Made New

The Reformation and Its Legacy

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Diarmaid MacCulloch 2016

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: MacCulloch, Diarmaid, author.

Title: All things made new : the Reformation and its legacy / Diarmaid MacCulloch.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016020307 (print) | LCCN 2016011764 (ebook) | ISBN9780190616823 (updf) | ISBN 9780190616830 (epub) | ISBN 9780190616816 (hardback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: ReformationEngland. | Reformation.

Classification: LCC BR375 (print) | LCC BR375 .M287 2016 (ebook) | DDC 270.6dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016020307

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For Felicity Bryan and Stuart Proffitt

Contents

Reformation history has been a huge growth industry over the last three decades: university libraries are bursting with a wealth of scholarship, but a lot of it is difficult to grasp and still very specialist. What I have tried to do in the varied essays in this book is to reflect on all that scholarship and then interpret it for a wider audience. I have divided the book into three sections of essays spanning my work over the last quarter-century: some are book reviews; some freestanding studies of particular topics. All have appeared in print before, though one of them so far only in Spanish; I am very grateful to the editors and publishers who have agreed to their reproduction here. I have chosen versions of the essays which reflect what I wanted to publish, rather than the texts which those with purer taste first put into print; I have also removed some over-detailed criticism of certain books, and smoothed out the immediacy of some contemporary references. Overall, in my choices of what to include, I have avoided over-technical studies or essays with a more local than national or international focus, but I have included one long piece on Robert Ware of Dublin because it is a bizarre tale and a detective story, which reveals how even good historians can fall for a con man. Some who know my work will look in vain for one of my better-known essays, The Myth of the English Reformation. It has become a casualty of its later influence on my arguments and the discussion around them, as the ideas in it inform much later writing. Its text would seem repetitive alongside other pieces included here, besides the fact that it would represent an early and only partly formed version of my thoughts. Its conclusions on the myth-making of Anglican history remain fundamental to my presentation of the Reformation.

These essays reflect my belief that the proper study of history has a purpose, indeed (to be portentous), a moral purpose: it forms a powerful barrier against societies and institutions collectively going insane as a result of telling themselves badly skewed stories about the past. I have concentrated my efforts over the years on the sanity of Anglicanism, which like all belief-systems making a claim to special authority, has frequently based its claims on skewed stories. But these essays are not just directed to Anglicans, and I would be offended to be described as an Anglican historian rather than as a historian who is also an Anglican. I hope that readers will find glimpses of sense in what follows, as well as entertainment and perspectives on the past which seek to look past accumulated prejudices, including my own.

These essays are dedicated to two people who have benevolently shaped my career in writing and have become good friends in the process: my literary agent Felicity Bryan and my publisher at Penguin, Stuart Proffitt. They commissioned none of the essays gathered in this volume, so it is offered to show them what I was up to when I should have been getting on with writing for them.

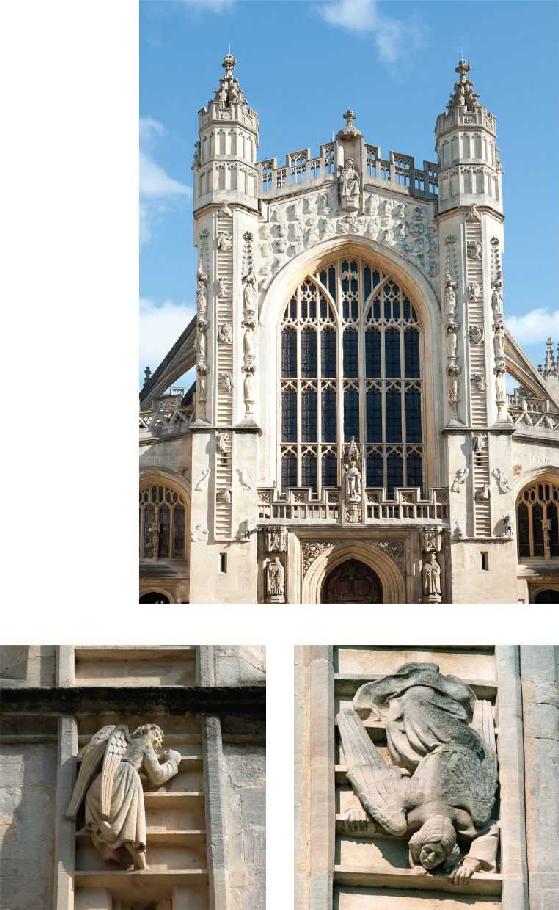

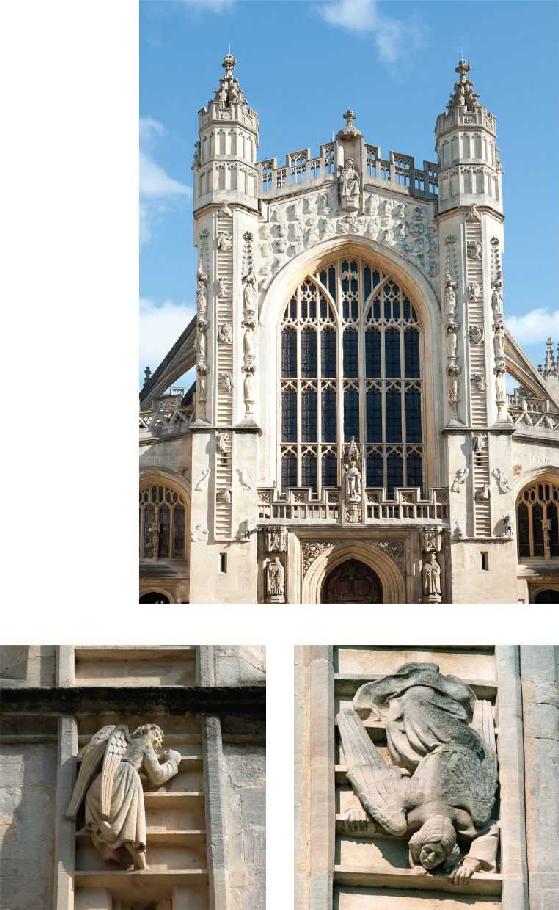

13. The west-front of Bath Cathedral Priory, featuring Jacobs Ladder, commissioned by Oliver King, Bishop of Bath and Wells, c. 1500. With engaging literalism, some of its angels descend to earth headfirst, while others more fortunate ascend to heaven (see Ch. 2).

4. Lucas de Heere, Allegory of the Tudor Succession, c. 1572 (see Ch. 7).

5. A commemorative group portrait of delegates at the Somerset House Conference, 1604, by an unknown artist. Spanish delegates sit on the left, English on the right (see Ch. 12).

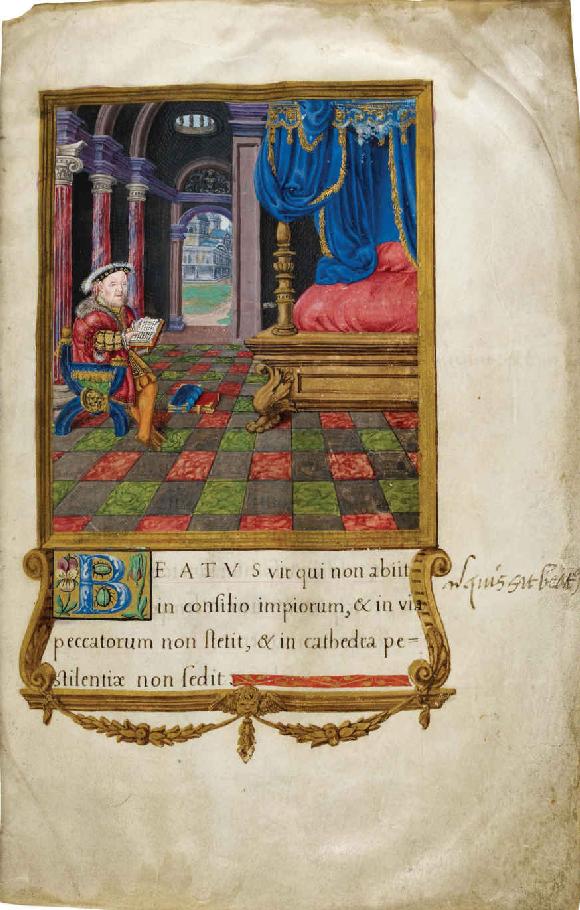

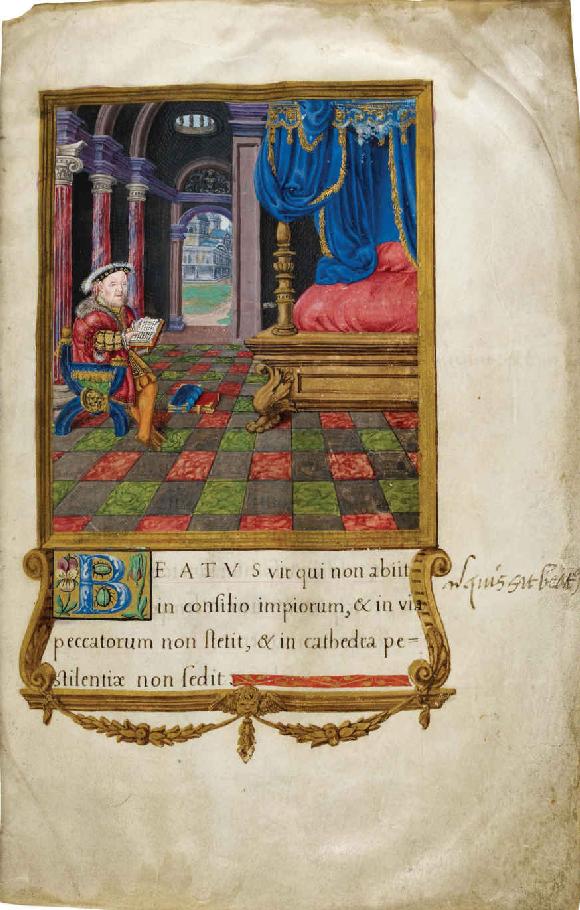

6. The opening of Psalm 1 in Henry VIIIs Psalter, annotated by the King (see Ch. 8).

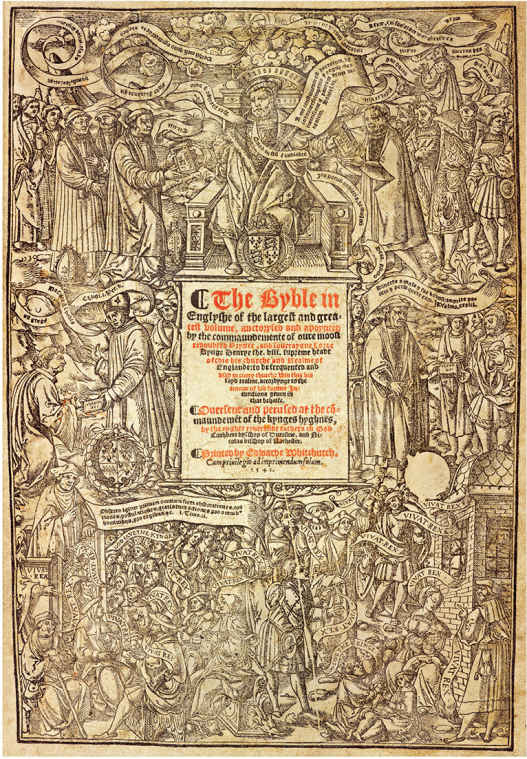

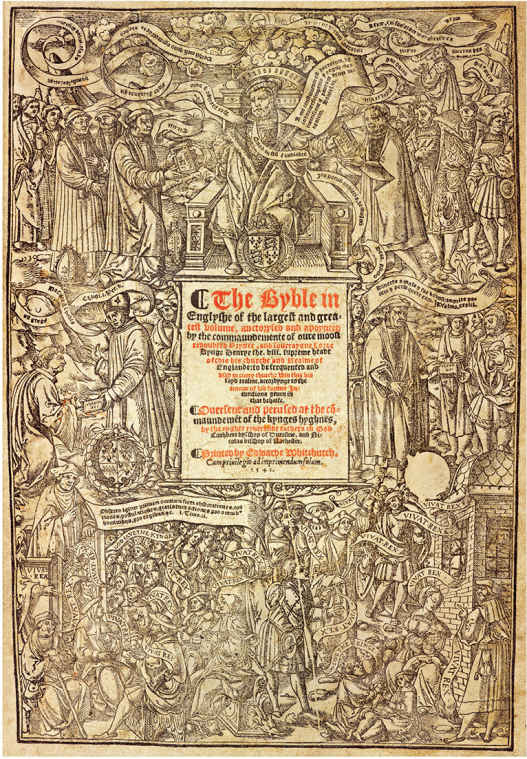

7. The Great Bible, authorized by Henry VIII. In this 1541 edition, the blank oval to the right represents the Stalinesque removal of Thomas Cromwells heraldry after his execution; Archbishop Cranmers arms opposite remain untouched (see Ch. 8).

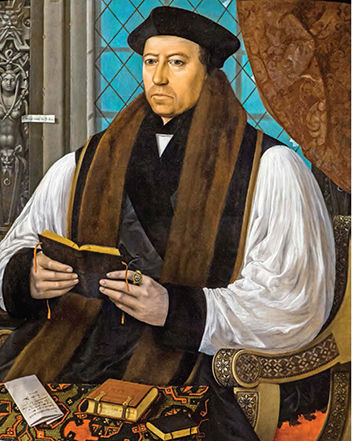

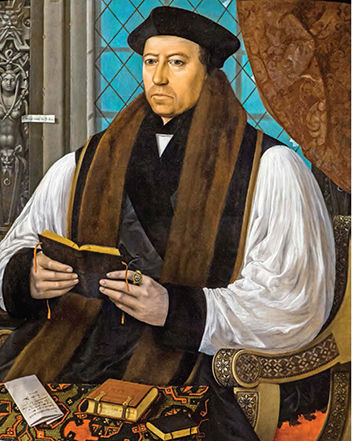

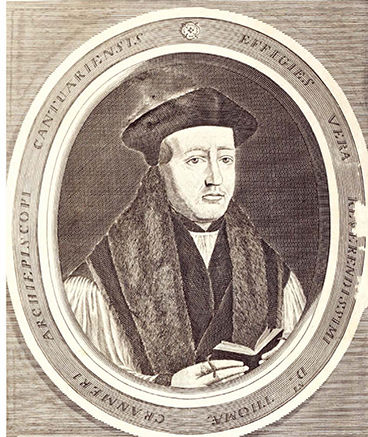

8. Thomas Cranmer, c. 1545, in a portrait by Gerlach Flicke.

9. A portrait of Cranmer derived from Flicke, in Gilbert Burnets History of the Reformation (167982).