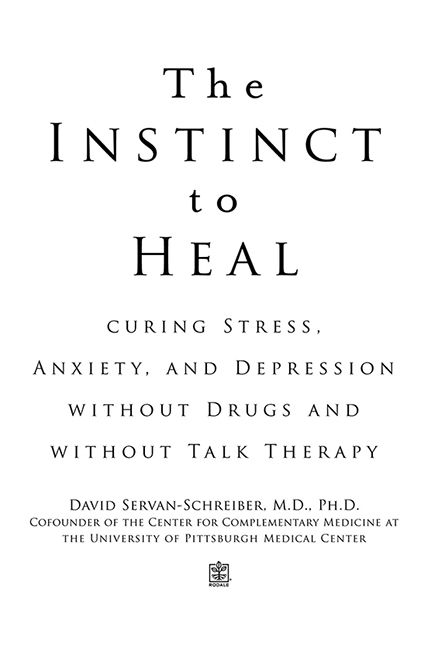

H eal is a powerful word. Isnt it presumptuous for a physician to use such a word in the title of a book on stress, anxiety, and depression? Ive thought a lot about this question.

To me, healing means that patients are no longer suffering from the symptoms that they complained of when they first consulted, and that these symptoms do not come back after the treatment has been completed. This is what happens when we treat an infection with antibiotics. This is also precisely what I have observed when I started to practice with the methods described in this book, and this is borne out by some of the research studies. In the end, I decided it was alright to use heal in the title of the book, because not using it would have been dishonest.

The ideas presented in this book are largely inspired by the works of Antonio Damasio, Daniel Goleman, Tom Lewis, Dean Ornish, Andrew Weil, Judith Hermann, Bessel van der Kolk, Joe LeDoux, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Scott Shannon, and many other physicians and researchers. Over the years, we have taken part in the same conferences, talked to the same collegues, and read the same scientific literature. Of course, there are many areas of overlap, common references, and similar ideas in their books and this one. However, coming after them, I have had the liberty to draw on their talent for exposing scientific ideas in simple, understandable terms. I wish to thank them here for all that I borrowed from their works and for any good idea that this book may contain. Of course, ideas with which they may not necessarily agree remain my entire responsibility.

All the cases of patients presented in the following pages are drawn from my own clinical experience, except for a few that were described in the scientific literature and that are referred to as such. Naturally, names and all identifying information have been changed to protect the confidentiality of the patients described. For literary reasons, I have chosen, in a few instances, to bring together the clinical features of two different patients into a single story.

1

A New Emotion Medicine

Doubting everything and believing everything are two equally convenient solutions that guard us from having to think.

Henri Poincar, Of Science and Hypotheses

E very life is unique and every life is difficult. We are often surprised at our own envy toward someone else.

If only I were beautiful like Marilyn Monroe.

If only I were a rock star.

If only I lived the adventures of Ernest Hemingway.

By becoming someone else, we would not have our usual problemsthat much is true. But we would have otherstheirs!

Marilyn Monroe was perhaps the sexiest, most famous, and most coveted of all women of her generation. Yet, she always felt lonely and she drowned her distress in alcohol. She eventually died of an overdose of barbiturates. Kurt Cobain, the lead singer of the rock band Nirvana, became a superstar over a few years. He killed himself before he reached 30. Hemingway, whose Nobel Prize and extraordinary life did not save him from a deep existential void, also committed suicide. Neither talent, nor glory, power, money, or the admiration of women and men can make the essence of life fundamentally easier.

There are, however, people who seem to live with harmony. Most often they have the feeling that life is generous. They are able to enjoy the people around them and the little pleasures of every day: meals, sleep, projects, relationships. They do not belong to a cult or a specific religion. They do not live in a particular country. Some are rich, others are not. Some are married, others live alone. Some have special talents, others are quite ordinary. They have all experienced failures, disappointments, dark moments. Nobody escapes from hardships. But on the whole, these people seem better equipped to overcome obstacles. They seem to have a special ability to get through misfortune, to give meaning to their lives, as if they had a closer relationship with themselves, with others, and with what they have chosen to do with their existence.

How does one become so resilient? How can we build a propensity toward happiness? I spent 20 years studying and practicing medicine, mainly in major universities of the United States, Canada, and France, but also with Tibetan doctors and Native American shamans. Over that time, I found certain keys that turned out to be useful for my patients as well as myself. To my surprise, these were not the methods Id learned at the university. They involved neither drugs nor the usual talk therapies.

The Turning Point

I did not come to this conclusionand this new style of medicineeasily. I started my career in medicine as a purebred scientist. After graduating from medical school, I left medicine for five years in order to study how neurons arrange themselves in networks to produce thoughts and emotions. I did a Ph.D. in cognitive neuroscience at Carnegie Mellon University under the supervision of Herbert Simon, Ph.D., one of the handful of psychologists ever awarded a Nobel Prize, and of James McClelland, Ph.D., one of the founders of modern neural network theory. The main result of my thesis was published in the journal Science, a prestigious publication in which every scientist hopes to see his work appear one day.

After this training in hard sciences, it was actually difficult for me to return to the clinical world and to complete my residency in psychiatry. Working with patients seemed too soft, too vague, almosttoo easy. Clinical work had very little in common with the hard data and mathematical precision that I had become accustomed to. However, I reassured myself that I was learning how to treat psychiatric patients in one of the most hard-nosed and research-oriented departments of psychiatry in the country. At the University of Pittsburgh, it was said that psychiatry received more federal research funding than any other department in the school of medicine, including the prestigious department of transplant surgery. With a certain hubris, we thought of ourselves as clinical scientists.

Shortly after that, I was awarded enough grants from the National Institutes of Health and from private foundations to start my own laboratory. Things could not have looked more promising and my curiosity for new knowledge, and for solid facts, promised to be fed. However, in short order, a few experiences would change my view of medicine completely, and also change the course of my career.

One was a trip to India, for the medical relief group Doctors Without Borders/Mdecins Sans Frontires, for whom I worked as a member of the United States board of directors from 1991 to 2000. I was going to India to work with Tibetan refugees in Dharamsala, the home base of the Dalai Lama. There, I observed a traditional Tibetan medicine in which practitioners diagnosed diseases and imbalances through lengthy palpation of the pulses of both wrists and inspection of the tongue and urine. These practitioners treated only with acupuncture, traditional herbs, and the instruction to meditate. They seemed every bit as successful with a variety of patients suffering from chronic illnesses as we were in the West, yet their treatments had remarkably fewer side effects and cost a lot less.