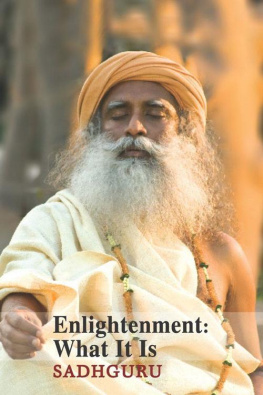

ADIYOGI

THE SOURCE OF YOGA

SADHGURU

& ARUNDHATHI SUBRAMANIAM

CONTENTS

I ts time to do a book on Adiyogi, Sadhguru says one day.

I try to look interested.

Adiyogi, he repeats. Shiva.

I nod.

It doesnt interest you? he says quizzically. It is more statement than question.

Since I have learnt over the years that it is difficult to conceal most things from this person who has become my guru, I launch into a tactful explanation. Of course, Shiva is the most enigmatic god in this subcontinent, I begin.

He isnt a god, Sadhguru says crisply.

I know he enjoys playing contrary. I do too. But today I am determined to remain non-reactive. I opt for a poets approach. Its true hes an inspired symbol for the dance of life and death. And as the cosmic dancer, he distils concepts of time, space, motion and velocity into stupendous iconography. I grow more fluent as I warm up to my theme.

Hes much more than that, Sadhguru cuts in. And his legacy isnt limited to this subcontinent.

Why not a book on you? I say in a flash of inspiration. A book on a living yogi? Having written Sadhgurus life story, I know there is still much of his unimaginably eventful inner life that remains undocumented.

Hes the worlds first yogi. The only yogi. The rest of us are just his sidekicks.

I decide Ive spent enough time on diplomacy. I plunge into argument. Theres just too much Shiva in the air. Its an epidemic. Calendar art, television serials, pop literature, science fiction. Hes everywhere. Why keep harping on our ancient heritage? Its all too zeitgeisty. Too revivalist. Lets talk about something here and now. We dont need another book on Shiva.

Hes here and now, Sadhguru says quietly.

I pause.

Hes my fifty per cent partner in everything I do.

I have heard Sadhguru say this before, but this time it seems less rhetorical. After twelve years around him, I am not entirely unused to the gnomic utterances of mystics. Sadhgurus deepest insights, Ive discovered, are invariably tossed off mid-sentence, in parentheses, or as a throwaway line in a conversation. The remark is so casual now that I sense gravitas. I grow alert.

Metaphorically, you mean?

The question stays unanswered.

Hes here and now? I repeat.

Hes my life breath.

And that is, I suppose, when I give in.

Its not that I understand what Im getting into. But I console myself with simple logic. While he can be infuriatingly unreasonable on occasion, Sadhguru still remains the most interesting person I know. Which means his fifty per cent partner cant exactly be tedious company.

And so, this is a book on Adiyogi.

But it is not as simple as that. Let me explain. This book is not an exercise in scholarship. Neither is it a work of fiction. Instead, this book is, for the most part, a kind of spiritual stenography. In short, a living guru becomes a channel or conduit for Shiva or Adiyogi.

A channel? The word can be disconcerting, Im aware. Let us return to the word later.

For now, let me qualify that while it was not based on conventional research, the library was certainly an important source of material for this book. Except that it was a mystical library, not a material one.

On his annual sojourns to Mount Kailash in the Himalayas, Sadhguru seems to replenish his already considerable understanding of Adiyogi, his life and his work. And so, it is not a coincidence that many of the conversations that provided fodder for this book actually unfolded on a journey to this enigmatic mountain in Tibet.

Other reference points were the yogic tradition and the already sumptuous resource of Indian myth. But even here, it was Sadhguru who played the dual roles of medium and yogi. And for him, there was really no contradiction one role was a seamless extension of the other. For yoga, he often says, is not for him an acquired knowledge system. It is the wisdom of his marrow, his bloodstream. An internalized wisdom. The mode by which he received it was not instruction. It was transmission an ancient mode of spiritual pedagogy. That makes him a living archive except that this is a man who is incapable of being turgid or pedantic. For me, he is always a reminder that mystical wisdom can be recognized by how lightly it is worn. He wears his with the careless panache with which he drapes his handwoven shawls.

I am not spiritually educated, he has often reiterated. I dont know any teachings, any scriptures. All I know is myself. I know this piece of life absolutely. I know it from its origin to its ultimate nature. Knowing this piece of life, one knows, by inference, every other piece of life. This is not sorcery; this is science the science of yoga available to everyone who cares to look inward.

And if Adiyogi is the primordial yogi, and even Sadhguru his sidekick, what does that make me? For the most part, I was just a stupefied scribe, vaguely aware that it was a privilege to be present as a unique mystical download took place.

I use the word unique with care. Let me say at the start that Im uncomfortable with tourist brochure idiom, the sticky superlatives of propaganda, whether commercial, political or religious. But there is no doubt in my mind that Sadhgurus utterances on Shiva add up to an unusual document. Strange, but unique.

But first, lets map the terrain.

Shiva or Adiyogi, as Sadhguru prefers to call him (in accordance with the yogic tradition to which he is heir) has been seen as the Ur-divinity of the world: wild, pagan, indefinable. He is apparently older than Apollo, the Olympian god of the Greeks, with whom he shares several characteristics as healer, archer, figure of beauty, harmony and light, symbolic of the sun, contemplation and introversion. He seems older too than Dionysus, the other Greek deity who shares many of his characteristics as the god of ecstatic delirium, dance, libido, intoxication, dissolution, protector of the freedoms of the unconventional, divine conduit between the living and the dead. Shiva has been seen as supreme godhead, folk hero, benevolent boon-bestower, shape-shifter, trickster, hunter, hermit, cosmic dancer, creator, destroyer. The epithets are endless.

There is no dearth of literature on Shiva. He has been the subject of passionate paeans by the saint poets of India down the centuries. He has been the subject of esoteric texts and metaphysical treatises all over the subcontinent. In recent times, he has been fictionalized, re-mythicized, sometimes bowdlerized, New-Agey-fied. But, oddly enough, he seems more in vogue than ever.

Far too elemental to be domesticated, hes more emblem than god, more primordial energy than man. Pan-Indian calendar art continues to paint him in the language of hectic devotion and lurid clich: blue-throated, snake-festooned, clad in animal skin, a crescent moon on his head. Sometimes he is presented in a cosy picture as a beaming family man with wife and children, all of whom stand aureoled in a giant lemon of a halo. While this pop idiom is not without its own charm, everyone, including the average Indian, is aware that there is more to Shiva than that.

No one can quite define who or what he is. But we all instinctively know him as the feral, tempestuous presence that has blown through the annals of sacred myth since time out of mind. Philosophers, poets, mythologists, historians, novelists, Indologists, archaeologists have all contributed to the avalanche of Shiva literature down the centuries. It is a literary inheritance of considerable magnitude and no mean import.

Next page