Copyright

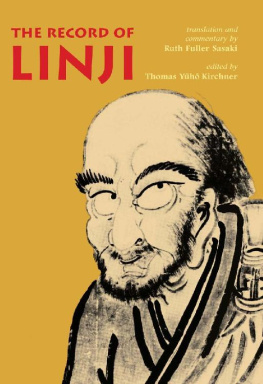

2009 University of Hawaii Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

14 13 12 11 10 09 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Yixuan, d. 867.

[Linji lu. English & Chinese]

The record of Linji / translation and commentary by Ruth Fuller Sasaki ; edited by

Thomas Yuho Kirchner.

p. cm.

Includes original Chinese text.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8248-2821-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8248-3319-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Linji (Sect)Early works to 1800. 2. Zen BuddhismEarly works to 1800.

3. Yixuan, d. 867. Linji lu. I. Sasaki, Ruth Fuller, 18921967. II. Kirchner, Thomas

Yuho. III. Title.

BQ9399.I554L5513 2008

294.3'85dc22

2008028329

The typesetting of this book was done by the Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture.

University of Hawaii Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources.

Printed by The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group

Foreword

Y amada Mumon

I ndian B uddhism is distinctly contemplative, quietistic, and inclined to speculative thought. By contrast, Chinese Buddhism is practical and down-to-earth, active, and in a sense transcendental at the same time. This difference reflects, I believe, the national characters of the two peoples. Zen, the name given to the Buddhism the first Zen patriarch Bodhidharma brought with him to China when he came from India, proved well suited to the Chinese mentality, and achieved a remarkable growth and development in its new environment. An Indian would no doubt find incredible the Chinese Zen master Baizhangs famous saying, A day of no work is a day of no eating.

The lines, One flower opens five petals / The fruit naturally ripen, traditionally attributed to Bodhidharma, are said to foretell the branching off of the five Zen schools that later appeared in China. These schoolsthe Yunmen, Guiyang, Linji, Fayan, and Caodongderive their names from their founders, and their overall complexions also are traceable to the respective personalities of those men. Zen attaches the highest importance to each persons particular individuality, even as it concerns itself with that persons universality. The Linji or Rinzai school of Zen begins in the figure of the Tang priest Linji Yixuan (J. Rinzai Gigen). The Linji lu, in Japanese the Rinzai roku, is the record of his words and deeds.

Rinzai Zen is distinguished from the other Zen schools by its brusque and somewhat martial disposition. Its central concern is the person who is master in all places, whose effortless activity is a giving and taking away, creating and annihilating absolutely at will, with the sword that kills, and the sword that gives life. This is one reason the school has been given the label Shgun Zen, and no doubt also accounts for the great success it enjoyed in the past among the samurai classes of Japan.

Editors note: Yamada Mumons Foreword and Furuta Kazuhiros Preface have been reprinted in close to their original form, but with some sections retranslated and with the Chinese names changed from Wade-Giles to Pinyin.

Nishida Kitar, the greatest Japanese philosopher of modern times and lifelong friend of the late Suzuki Daisetz, held the Linji lu in special regard. He once wrote, If there should come a time when books were to disappear from the earth, or I was banished to some bookless land, it would be enough for me if I had only Shinrans Tannish and the Linji lu.

I believe that Zen, particularly Rinzai Zen, has a significant role in the present world. Modern people are adrift amid the great confusion and uncertainty of contemporary life. The Linji lu can give us a foundation on which to construct a new and powerful view of human existence.

It thus gives me great joy to know that with the appearance of this first English translation of the Linji lu, this Zen classic will be available more than ever before to readers throughout the world.

Kyoto, Institute for Zen Studies

Preface to the 1975 Edition

F uruta Kazuhiro

T he Linjilu (J. Rinzai roku) consists of the recorded sayings of Linji Yixuan (d. 866), the founder of the Linji school of Chan (Zen) Buddhism, which emerged toward the end of the Tang dynasty (618907). Linjis lifetime coincided with the declining years of the mighty Tang empire, when Chinese society was in a state of great turmoil.

Buddhism, initially transmitted to China in the first century, gradually became more Sinified from the fourth century on. During the sixth and seventh centuriesthe Sui (581618) and early Tang dynastiesa systematic organization of the Buddhist teaching took place, reaching a peak in the philosophical structures of the Tiantai, Sanlun, Huayan, Faxiang, and Jingtu (Pure Land) schools.

Linji shook himself free from the standardized views of humanity and religion prevalent in the historical period he lived in, and proclaimed a new Buddhism based on the personal experience of reality in a free and open mode of life. His voice carries to us across the centuries in the pages of the Linji lu.

Traditionally, Chan traces its origins in China back to Bodhidharma, the First Patriarch, who is said to have arrived there in the sixth century. Chan came to maturity at the time of Huineng (638713), the Sixth Patriarch. Huinengs dharma was inherited by Linji after passing through four generations of illustrious Chan masters: Nanyue Huairang (677744), Mazu Daoyi (709788), Baizhang Huaihai (720814), and Huangbo Xiyun (d. ca. 850). The Linji lu, then, can perhaps be regarded as providing a true index of this tradition of Chan at the end of the Tang dynasty. Although Chan later branched out into the Five Houses and Seven Schools, by the Northern Song dynasty (9601127) the school established by Linjis descendents had assumed preeminence as the central line.