FOREWORD

by Sean Murphy

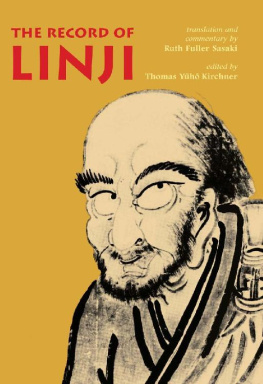

A lthough its not as widely known as it ought to be, the first American known to experience satori, one of the first to ordain as a monastic in the Japanese Zen tradition, and the first to become abbot of a Japanese temple was a woman: Ruth Fuller Everett (later Fuller Sasaki). The first acknowledged Zen master to live and teach in America and bury his bones here was Sokei-an Sasaki. In a remarkable case of what? synchronicity? karma? the two met and became, first, collaborators and, later, husband and wife.

This important book of Zen firsts provides, for the first time, the full story of these key figures in the unfolding of Zen in America, in a colorfully readable and engaging narrative of East meeting West a meeting that, as of this writing, has blossomed into a marriage in its own right.

If not for these two pioneers, and their partnership, Zen might never have taken root in the West a feat that, in Sokei-ans words, was like holding a lotus to a rock. As one of the many who have walked in their footsteps in the years since, I owe them a great debt of gratitude. That gratitude extends now to the existence of this fine book. Nine bows to Janica Anderson and Steven Zahavi Schwartz for their excellent work in bringing these Zen pioneers to the eyes of a new generation.

Sean Murphy, author of One Bird, One Stone: 108 Contemporary Zen Stories

FOREWORD

by Joan Watts

R uth Fuller (Everett) Sasaki was a study in contrasts and contradictions.

I knew her as Granny Ruth. During the era of this story, I was a young child, and Granny lived in a brownstone on the east side of Manhattan in what would be considered high style. When she traveled to see us in Evanston, Illinois, her visits always brought much excitement for me and my sister, Anne. Shed arrive, having taken the Pullman sleeper from New York to Chicago, and would be deposited by taxi on our doorstep wearing hat, gloves, furs, and sensible shoes, and with a full set of Mark Cross luggage. Her hugs and kisses were punctuated by her signature scent of violets and freshly powered cheeks. She always brought gifts that would delight us. When we visited her in New York City, wed be treated to trips to FAO Schwarz, museums, ice cream parlors, the ballet, and the Rockettes at Radio City Music Hall.

Wed also amuse ourselves in her amazing five-story home. Once inside, off the hustle and bustle of city streets, the ambiance was quiet and elegant. I remember spending hours exploring the various rooms. The first floor had an entry and dining room, main kitchen, and an elevator, which we loved to ride instead of mounting the sweeping stairway to upper floors.

There, for us, the mysterious began. On the second floor was the meditation hall ( zendo ) of the Buddhist Society of America, where people came and went, sitting in the darkened hall for hours. Wed hear occasional chanting, gongs reverberating, and clappers clapping. The scent of incense hung heavily in the air. A large library opposite the zendo had a grand piano, shelves to the ceiling with hundreds of volumes including Zen texts in Chinese and Japanese, chintz-covered sofas on either side of a large fireplace, and Asian art objects including a beautifully painted Japanese screen. There was even a kitchenette where tea was made for students and guests. Behind that was an incredible laundry room with a floor-to-ceiling dryer where freshly washed clothes were hung to dry.

The third floor had two large suites. One was Granny Ruths bedroom, with large oak beds made of sixteenth-century English choir stalls, Grannys vanity, a wall of closets, and a bathroom. The other suite was Sokei-ans room and their combined study. There was a beautiful carved red-and-gold lacquer bed from Beijing where Sokei-an slept. His bathroom was decorated with a pine forest motif, and it was stocked with his favorite pine-tar soap.

The fourth floor was a guest apartment with a living room and small kitchen, two bedrooms, and an outdoor patio with huge ceramic foo dogs. The fifth floor was the servants apartment, occupied by Lawrence the butler, a gracious man, and Kitty the cook, Lawrences pretty wife. Several other servants lived out.

Sokei-an Sasaki was a wonderfully peaceful man. Everything he did was carefully executed or quietly spoken. I sensed Granny and Sokei-an were very devoted, that she would move heaven and earth for him, that he was indebted to her for her help. Together they continued his mission to translate medieval Chinese Zen texts.

I remember Sokei-an giving lectures in the zendo. I remember him eating a breakfast of applesauce with cinnamon, served by Lawrence in the main dining room, with Chaka, his beautiful cat, sitting by his side. I remember students coming and going from the zendo and library, quietly discussing their studies and the war. I remember Sokei-ans internment, Grannys despair and fear, and his release from prison and his illness.

What I remember most was his death. My mother brought me with her to New York on the overnight train me with my favorite teddy bear. I remember the hush and sadness permeating the entire household. I remember attending services in the zendo honoring those who died in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I remember that after his death I slept in his bed during visits. I remember pondering his death mask, beautiful and peaceful, which hung over the fireplace in the room that was now only Grannys study. I played with the index cards, colored pens, pencils, and paper clips on her desk; Chaka wandered through rooms and basked in the sunlight on a windowsill.

After Granny Ruth returned to Japan, determined to finish the translation work that was Sokei-ans mission and to continue her studies, I lived at her small subtemple, Ryosen-an, for a year in the late 1950s. I watched the construction of the library and zendo and the creation of the gardens. A large pine tree was carefully balled and moved to make room for the zendo.

Ruth was in her element, directing household staff and scholars, and entertaining guests from around the world, serving up delicious Japanese and American meals for appreciative guests, knees akimbo as they sat on the dining room tatami. She made amazing apple pies. After dinner she would smoke her Benson & Hedges cigarettes and regale guests with stories of past travels, including trips she made on the Orient Express across Europe, Russia, and China, during which she was served Beluga caviar in a large bowl of crushed ice.

The simple Japanese-style home had no running hot water, no bathroom plumbing (farmers collected the waste for their fields), no central heating it was a damp, raw cold in the winters with only braziers to warm ones cold hands and feet. She slept on a futon on the tatami under heavy quilts. Her room was also her study, where she sat on a zabuton at her desk, with countless index cards of Chinese characters, their meaning carefully noted; dictionaries; volumes of Chinese Zen texts; and a typewriter. At the end of the day, she would invite visitors and scholars to join her for a martini with rakyo , her favorite pickled onion with just a touch of sweetness. She tolerated the hot, humid summers and monsoons. She still maintained some of her creature comforts tweed suits, cashmere sweater sets, silk blouses, and Rubinstein cosmetics, which she periodically ordered from Bergdorf Goodman. In the summer she wore thin cotton dresses. She always wore her pearl earrings.

During this time she was officially ordained a priest at the head temple in Daitoku-ji and was named abbess of Ryosen-an, a remarkable feat for a foreigner, let alone a woman.

Granny Ruth was without a doubt a driven woman, exceptional in her abilities to take on challenges. She accomplished most of what she wanted in life, but not without ruffling some feathers and making a few enemies along the way. There were those who doubted her loving relationship with Sokei-an, who were jealous of her abilities, and who condemned her wealth. However, her contribution to the understanding of Rinzai Zen is unequivocal. In many ways, I considered her an intellectually pure student and practitioner of the subject, while my father, Alan Watts, also a scholar and a driving force for the interest in Buddhism in the United States, was primarily a popularizer of the subject. Her writings and translations will undoubtedly endure for generations to come.

Next page