The Editor

H ERBERT M ARKS is Professor of Comparative Literature at Indiana University, where he also directs the Institute for Biblical and Literary Studies and edits the monograph series Indiana Studies in Biblical Literature.

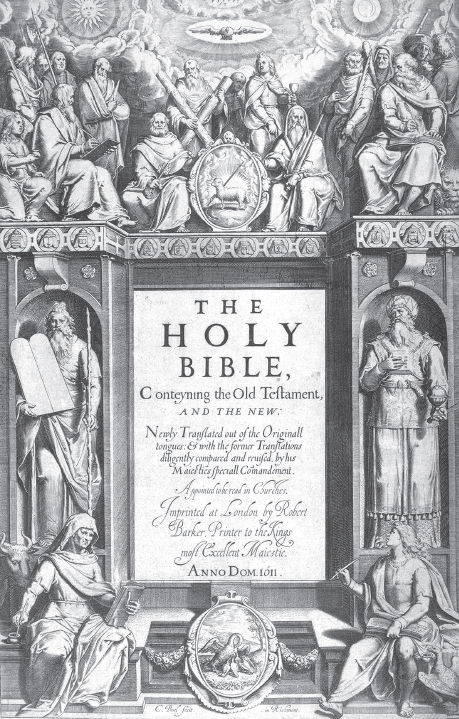

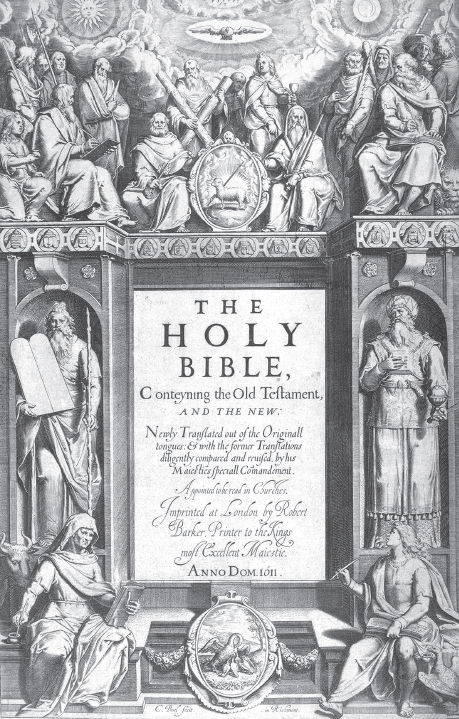

General title page of the first edition of 1611; copperplate engraving by Cornelius Boel of Richmond. To the left and right stand Moses carrying the tablets and Aaron wearing the priestly mitre and vestments. Seated above the frieze, which carries emblems of the twelve tribes, are Peter and Paul surrounded by the remaining apostles. Between them is an image of the Lamb, representing Christ; above that an image of the Dove, representing the Holy Spirit; and at the very top the tetragrammaton, the four-letter name of God (YHWH) in Hebrew. The four evangelists are seated in the corners with their familiar symbols, Matthew and Mark above, Luke and John below. A second medallion at the bottom shows a pelican vulning, or wounding herself to feed her young, a symbol of Christs work of atonement.

Contents

The Kingdom of David and Solomon and the Divided Kingdom

Preface

The Norton English Bible brings together three collections of ancient literature. The present volume contains the Hebrew Biblehere called by its traditional English name, the Old Testamentan anthology of ancient Hebrew literature, of which the earliest page probably dates to the second millennium and the latest to the second century b.c.e. Volume II, edited by Gerald Hammond and Austin Busch, contains the New Testamenta collection of early Christian texts composed in Koine Greek between 50 and roughly 160 c.e.together with the so-called Apocrypha, miscellaneous writings from the Hellenistic period that never achieved the status of sacred scripture among the Jewish communities of Babylonia and Palestine. It was of course the combination of the first two collections that turned the Hebrew Bible or Tanak (from the initials of its three sections: Torah, or Law; Neviim, or Prophets; and Ketuvim, or Writings) into the Old Testament in the first place. Christian bibles appropriate the Hebrew writings and read them prophetically as a prelude to the New Testament. The result is a kind of hybrid, whose unity was a crucial question for the definition of Christianity.

But the Norton Bible is a hybrid in a second sense. Through its annotations, headnotes, introductions, and appendices, it offers the reader an introduction to the modern study of an ancient text, yet it presents that text in the King James Version (often known in Britain as the Authorised Version)that is, in a Renaissance English translation that, for all its rhetorical splendor, contains obsolete vocabulary and diction, a significant number of mistranslations, and, in the case of the Old Testament, a tendency toward Christological readings that distort the meaning of the Hebrew. The reprinting of a four-hundred-year-old text as the basis for a modern study Bible is apt to seem more puzzling to biblical scholars than to literary critics or general readers, who appreciate that the KJV is by far the most influential English book ever published, a formative presence within the history of English literature, high and low, and within the very weave of the language. But a strong case may be made that the KJV deserves its privileged place, not only on historical and stylistic grounds, as a venerable relic and model of English prose, but as a faithful translation, a window onto the ancient texts, which, though it colors the original, distorts it less than do most modern versions.

In a sense the KJV was already an old translation at its first printing, for more than nine-tenths of it had been carried over unchanged from previous versions. Beginning with the pioneering work of William Tyndale and Miles Coverdale, English reformers had produced a half-dozen major translations by the time King James I called the Hampton Court Conference in 1604 in an effort to reconcile the English high clergywhose preferred text, the Bishops Bible, had been authorised to be read in Churches (a dignity never extended to the KJV itself)and those Puritans and Scots who favored the Geneva Bible, used throughout the realm for private worship and study. Both sides acknowledged the superiority of the Genevan scholarship, but James, like the bishops, was leery of the radical Calvinist strain in the copious annotation. Accordingly, when it was resolved to undertake one uniform translation free of doctrinal notes, the translators (some fifty scholars appointed from the universities) were directed to use the Bishops Bible as their base text, altering it as little as the truth of the original will permit but following other versions, from Tyndale to Geneva, where they agree better with the text of the Greek or Hebrew. In the words of the translators preface, their purpose was not to make a new Translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one, but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principal good one.

The result, when first published in 1611, was not immediately popular, but in time the suspicion turned to adulation, and from the beginning of the eighteenth century until the flood of new translations following World War II the Bible was synonymous with the King James Version throughout the English-speaking world. Its superiority to its successors as well as its predecessors may be argued on grounds of both content and style. Admittedly, modern translators have better manuscript sources, higher standards of textual scholarship, and a superior knowledge of the ancient languagesincluding some cognate Semitic languages whose very existence was unknown in the seventeenth centuryand yet, in the overwhelming majority of passages, the KJV remains the most literal of the major translations. For most modern translators, fidelity is a matter of meaning rather than form. Since the sense of an expression varies according to its context, they claim the freedom to vary the wording, to attempt to create a dynamic equivalent for the idea behind the words rather than render each word with the same English counterpart every time it appears. By definition, then, the sense offered the reader is always the translators sense of the sense. Yet for the Hebrew Bible, especially, where meanings depend on echo and allusion, variety of phrasing is often misleading. In his preface, Miles Smith, writing on behalf of the translators, also defends variation, distinguishing between reverence for the text and superstition (For is the kingdom of God become words or syllables?). But though the committees claimed the liberty to vary their wording, in practice they used that liberty with discretion, tending toward an ideal of formal equivalence as they weighed each verbal choice of their predecessors against the original. Not only in its vocabulary but in its syntax and word order, the KJV adheres word for word to the Hebrew more closely than its predecessors and far more closely than the principal modern versions. (See the Survey of English Translations in the Appendix. The somewhat different problems of the New Testament are discussed in Volume II.)

Next page