The Editors

G ERALD H AMMOND is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Manchester. A Fellow of the British Academy, his many publications include The Making of the English Bible; Fleeting Things: English Poets and Poems, 16161660; Sir Walter Raleighs Selected Writings; and John Skeltons Selected Poems. He contributed the essay on English Bible translation to The Literary Guide to the Bible.

A USTIN B USCH is Assistant Professor of Early World Literatures in the Department of English at the State University of New York College at Brockport. His articles have appeared in the Journal of Biblical Literature, Biblical Interpretation, and The Classical Journal. He is a contributing author of Seneca and the Self (Cambridge University Press).

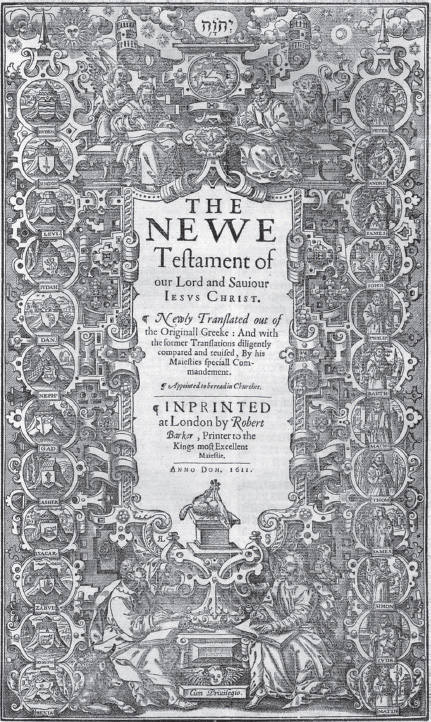

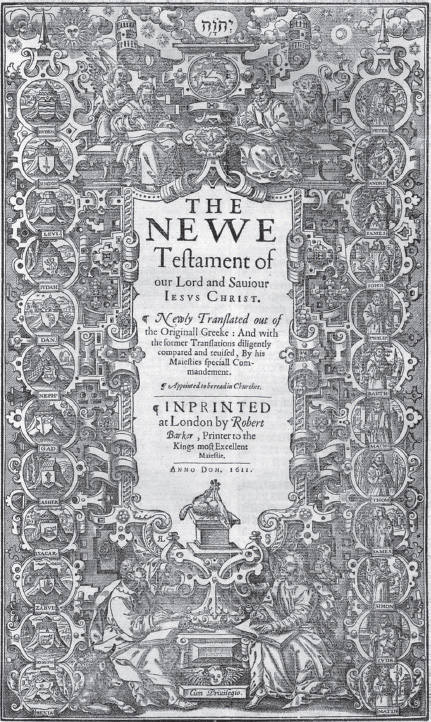

The 1611 KJV contained a separate title page for the New Testament. Its elaborate woodcut border, apparently recycled from previous editions of the Bishops Bible, displays at the center top the tetragrammaton, the four-letter name of God (YHWH) in Hebrew. Underneath it stands a victorious lamb, an image of the risen Christ, and underneath that is a dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit. Beneath the title pages text is an altar with a bound lamb awaiting sacrifice that figures Jesus death. At the corners of the bordered text sit the four evangelists with their associated symbols: Matthew accompanied by an angel, Mark by a lion, Luke by an ox, and John by an eagle. Toward the right are images of the twelve apostles (cf. Acts 1:13, 26); toward the left, tents of the twelve sons of Judah (roughly corresponding to Israels twelve tribes).

Contents

Preface: An Introduction to the New Testament and the Apocrypha

In 2 Corinthians 3:6, Paul writes that God hath made us able ministers of the new testament; not of the letter, but of the spirit: for the letter killeth, but the spirit giveth life. Readers sometimes assume that Paul contrasts the Christian gospel inscribed in the section of the Bible known today as the New Testament with the supposedly legalistic Judaism of the Old Testament. Some even take this verse as a hermeneutically programmatic passage that encourages readers to privilege the Bibles spiritual truth (whatever that might mean) over its literal significance, inferring that the New Testament offers a clearer view of this truth than does the Old, where it is putatively mired in obsolete legal codes and barbaric tales of a vengeful and violent God. Such a reading of 2 Corinthians 3:6 is erroneous on many levels.

The Greek word diathk, which the King James Version renders testament, refers to a covenant, promise, or pactoften, in the New Testament, one that God makes with his people. The Bible narrates Gods establishment of many such covenants and sometimes records their specific terms. When he uses the phrase old testament in 2 Corinthians, Paul refers to the covenant God made with Israel at Mount Sinai. The meaning of new testament is less clear, but in any case the eponymous divisions of the Christian biblical canon are not being invoked, for these did not exist as such until well after Paul wrote, and they received their traditional titles only from an anachronistic appropriation of this verse (probably beginning in the second century c.e.).

However we understand it, we probably ought not to call the new testament Christian. Paul never used the word Christian in his writings and our earliest evidence suggests that outsiders originally applied it to Jesus-believers; it was not something they called themselves (Acts 11:26; 26:28; 1 Pet 4:16). Paul understood himself to be a member of a Jewish religious movement that emphasized faithfulness to Jesus, the Messiah and Lord; the first historian of this movement, the author of the Acts of the Apostles, simply calls it the Way. That some of the Ways leaders were interested in reaching out to Gentiles, and that at least a few of them believed that non-Jews faithful to Jesus ought not to become circumcised, no more obviates the Ways essential Jewishness than does the frequent presence of Gentiles at synagogues throughout the Mediterranean world (at least according to Acts) obviate the Jewishness of these hellenistic Jewish congregations. In light of this observation, it should come as no surprise that Paul lifts the phrase new testament directly from the Hebrew Scriptures. He alludes in verse 6 and elsewhere in 2 Corinthians 3 to Jeremiah 31:3134, which anticipates Israels internalization of and spontaneous obedience to Gods lawa new and better covenant than the one God made with Israel at Sinai (though no more or less legal than it), and one in which Paul is convinced that Gentiles as well as Jews may participate. It is thus not of Christianity that Paul claims to be a minister. He rather presents a particular understanding of the Jewish Gods covenants with his people. In particular, he associates himself with Jeremiahs promise of a new covenant that will fulfill the unrealized potential of the one that God made with Israel at Sinai.

2 Corinthians 3:6, then, neither opposes the Christian to the Jewish nor refers to the divisions of the Bible later known as the New and Old Testament. It may be possible to infer from it a program for biblical interpretation, though the distinction between spiritual and literal meaning it is often invoked to justify seems so vague and subject to idiosyncratic application as to offer little reliable guidance. In light of the verses often realized potential for misinterpretation, perhaps the soundest advice it offers is this: read closely and with careful attention to echoes of other relevant literature, contextualize appropriately, and beware of anachronistic presumptions. The introductions and annotations to the biblical books that follow provide information aimed at facilitating such reading, as does the balance of this preface, which, before introducing the Apocrypha, explores four important New Testament matrices, understood at the same time as generative sources from which New Testament writers draw language and ideas and as conceptual systems with which they assume their readers familiarity.

The Biblical Matrix

The only Scripture that the New Testament writers knew was a version of what is today usually called the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament, although in this context neither title fits. Old Testament assumes a New Testament, which, as noted above, did not come into existence until after the texts it would include were composed. Hebrew Bible also misleads because New Testament writers normally quote from the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures probably initiated in Alexandria and produced piecemeal during the third to the first centuries b.c.e. Its conventional title and standard abbreviation (LXX) round off the number seventy-two, which figures prominently in a popular legend preserved in the

Next page