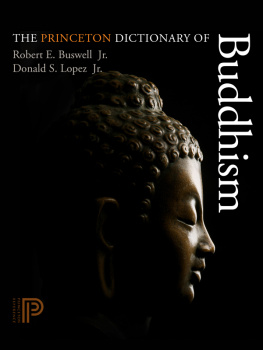

The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism

The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism

Robert E. Buswell Jr. and Donald S. Lopez Jr.

WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF

| Juhn Ahn | Sumi Lee |

| J. Wayne Bass | Patrick Pranke |

| William Chu | Andrew Quintman |

| Amanda Goodman | Gareth Sparham |

| Hyoung Seok Ham | Maya Stiller |

| Seong-Uk Kim | Harumi Ziegler |

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket Photograph: Buddha portrait. Anna Jurkovska. Courtesy of Shutterstock.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism / Robert E. Buswell, Jr. and Donald S. Lopez, Jr. ;

with the assistance of Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, Amanda Goodman, Hyoung Seok Ham, Seong-Uk Kim,

Sumi Lee, Patrick Pranke, Andrew Quintman, Gareth Sparham, Maya Stiller, Harumi Ziegler.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-15786-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-691-15786-3 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. BuddhismDictionaries. I. Buswell, Robert E., author, editor of compilation.

II. Lopez, Donald S., 1952- author, editor of compilation.

BQ130.P75 2013

294.303dc23

2012047585

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Adobe Garamond Pro with Myriad Display

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

Preface

At more than one million words, this is the largest dictionary of Buddhism ever produced in the English language. Yet even at this length, it only begins to represent the full breadth and depth of the Buddhist tradition. Many great dictionaries and glossaries have been produced in Asia over the long history of Buddhism and Buddhist Studies. One thinks immediately of works like the Mahvyutpatti, the ninth-century Tibetan-Sanskrit lexicon said to have been commissioned by the king of Tibet to serve as a guide for translators of the dharma. It contains 9,565 entries in 283 categories. One of the great achievements of twentieth-century Buddhology was the Bukky Daijiten (Encyclopedia of Buddhism), published in ten massive volumes between 1932 and 1964 by the distinguished Japanese scholar Mochizuki Shink. Among English-language works, there is William Soothill and Lewis Hodouss A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms, published in 1937, and, from the same year, G. P. Malalasekeras invaluable Dictionary of Pli Proper Names. In preparing the present dictionary, we have sought to build upon these classic works in substantial ways.

Apart from the remarkable learning that these earlier works display, two things are noteworthy about them. The first is that they are principally based on a single source language or Buddhist tradition. The second is that they are all at least a half-century old. Many things have changed in the field of Buddhist Studies over the past fifty years, some for the worse, some very much for the better. One looks back in awe at figures like Louis de la Valle Poussin and his student Msgr. tienne Lamotte, who were able to use sources in Sanskrit, Pli, Chinese, Japanese, and Tibetan with a high level of skill. Today, few scholars have the luxury of time to develop such expertise. Yet this change is not necessarily a sign of the decline of the dharma predicted by the Buddha; from several perspectives, we are now in the golden age of Buddhist Studies. A century ago, scholarship on Buddhism focused on the classical texts of India and, to a much lesser extent, China. Tibetan and Chinese sources were valued largely for the access they provided to Indian texts lost in the original Sanskrit. The Buddhism of Korea was seen as an appendage to the Buddhism of China or as a largely unacknowledged source of the Buddhism of Japan. Beyond the works of the Pli canon, relatively little was known of the practice of Buddhism in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. All of this has changed for the better over the past half century. There are now many more scholars of Buddhism, there is a much higher level of specialization, and there is a larger body of important scholarship on each of the many Buddhist cultures of Asia. In addition, the number of adherents of Buddhism in the West has grown significantly, with many developing an extensive knowledge of a particular Buddhist tradition, whether or not they hold the academic credentials of a professional Buddhologist. It has been our good fortune to be able to draw upon this expanding body of scholarship in preparing The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism.

This new dictionary seeks to address the needs of this present age. For the great majority of scholars of Buddhism, who do not command all of the major Buddhist languages, this reference book provides a repository of many of the most important terms used across the traditions, and their rendering in several Buddhist languages. For the college professor who teaches Introduction to Buddhism every year, requiring one to venture beyond ones particular area of geographical and doctrinal expertise, it provides descriptions of many of the important figures and texts in the major traditions. For the student of Buddhism, whether inside or outside the classroom, it offers information on many fundamental doctrines and practices of the various traditions of the religion. This dictionary is based primarily on six Buddhist languages and their traditions: Sanskrit, Pli, Tibetan, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. Also included, although appearing much less frequently, are terms and proper names in vernacular Burmese, Lao, Mongolian, Sinhalese, Thai, and Vietnamese. The majority of entries fall into three categories: the terminology of Buddhist doctrine and practice, the texts in which those teachings are set forth, and the persons (both human and divine) who wrote those texts or appear in their pages. In addition, there are entries on important placesincluding monasteries and sacred mountainsas well as on the major schools and sects of the various Buddhist traditions. The vast majority of the main entries are in their original language, although cross-references are sometimes provided to a common English rendering. Unlike many terminological dictionaries, which merely provide a brief listing of meanings with perhaps some of the equivalencies in various Buddhist languages, this work seeks to function as an encyclopedic dictionary. The main entries offer a short essay on the extended meaning and significance of the terms covered, typically in the range of two hundred to six hundred words, but sometimes substantially longer. To offer further assistance in understanding a term or tracing related concepts, an extensive set of internal cross-references (marked in small capital letters) guides the reader to related entries throughout the dictionary. But even with over a million words and five thousand entries, we constantly had to make difficult choices about what to include and how much to say. Given the long history and vast geographical scope of the Buddhist traditions, it is difficult to imagine any dictionary ever being truly comprehensive. Authors also write about what they know (or would like to know); so inevitably the dictionary reflects our own areas of scholarly expertise, academic interests, and judgments about what readers need to learn about the various Buddhist traditions.