1 FRANKENSTEIN

Philosophy and the Meaning of Life

2 THE MATRIX

Can We Be Certain of Anything?

3 TERMINATOR I & II

The MindBody Problem

4 TOTAL RECALL & THE SIXTH DAY

The Problem of Personal Identity

5 MINORITY REPORT

The Problem of Free Will

6 HOLLOW MAN

Why Be Moral?

7 INDEPENDENCE DAY & ALIENS

The Scope of Morality

8 STAR WARS

Good and Evil

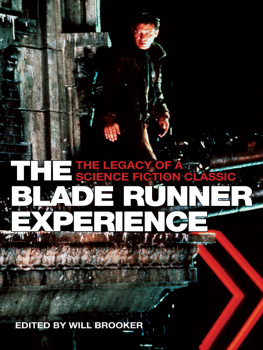

9 BLADE RUNNER

Death and the Meaning of Life

The Philosopher at the End of the Universe

Mark Rowlands

For Emma

I, Monster

WHY FRANKENSTEIN? THIS is supposed to be a book about sci-phi the philosophy embodied in science fiction so why begin with what is usually thought of as a gothic horror story? Bear with me. Gothic horror story it may be, but Mary Shelleys Frankenstein is also the very first work of science fiction. And what could be more appropriate than kicking off the genre of sci-phi by way of the work that kicked off the genre of sci-fi? Theres another reason, philosophical rather than genealogical. The story of Frankenstein and his monster is an absolutely brilliant story for illustrating one central philosophical concept: absurdity. And according to many philosophers, absurdity is a defining feature maybe the defining feature of human existence.

Sometimes our lives are absurd. In the ordinary sense, absurdity involves a noticeable discrepancy between aspiration or pretension and reality. You give a moving speech in favour of a certain motion, only to discover that the motion had already been passed while you were in the bathroom and you forgot to do your fly up anyway. You declare your undying love to someone only to discover that you were talking to her answering machine. You return to your seat in the cinema after a visit to the bathroom and give your significant other a quick squeeze, only to discover that you are in the wrong row, and the squeeze was of someone other than the other. Entire comedic genres have been based around this idea of absurdity, genres that, in Britain at least, largely seemed to involve peoples trousers falling down whenever the vicar arrived.

This idea of absurdity revolves around a clash of two perspectives we have on ourselves a view from the inside and a view from the outside. The clash is between the significance of our actions to ourselves, and their significance to others. Or, put another way, the clash is between what we think we are achieving in making the speech, declaring our love, squeezing our significant other, and what we are actually achieving. Whenever we have this sort of clash between pretension and reality, some form of absurdity is always on the cards.

Dreams provide an extreme example of the sort of dissonance that can arise between what we think we are achieving and what we are actually achieving. Suppose you are having a dream of some sort. In fact, lets make it an interesting one a romantic entanglement with a partner of your choice. And when you have this dream, it certainly seems to you as if you are achieving something precisely what depends on how long you can put off the rather disappointing waking-up thing. This is the view from the inside, the realm of pretension or aspiration. Here, the move from the sublime to the ridiculous is easily achieved. All we need to do is give you an outside. For example, we imagine that when you were dreaming you were located in some public place a crowded waiting room, for example.

If you were unfortunate enough for this to happen to you and I, of course, was then you will know exactly where the story of Frankenstein is coming from. If you want to know what its like to be looked at as if you are a monster, try having a wet dream in front of a roomful of Catholics.

Absurdity and the Human Situation

One way of looking at the difference between philosophy and everyday life is that, whereas in everyday life situations are sometimes absurd, in philosophy, they always are. Absurdity not only permeates the whole of human existence, it also lies at the core of philosophy and its problems.

In philosophy, absurdity is an industry term favoured by French existentialist philosophers such as Sartre and Camus.views we have of ourselves, one from the inside, one from the outside, just do not mesh. And whenever we have this sort of dissonance, absurdity is just around the corner.

It is here that we find the genesis of the most fundamental philosophical problem the problem of the meaning of life. The problem is one of explaining our ultimate significance given our place in a universe that does not seem to allow us to have any such significance. The problem derives from the thought that there are two quite different stories we tell about ourselves. The first story concerns the way we seem to ourselves the way we appear from the inside. The precise details of this story, of course, vary from person to person. But what is common to all these stories is that each one of us is at its centre we are the major character, the figure around which the plot revolves. We, therefore, matter to the story. We are, each one of us, a locus of meaning, a core of significance.

On the other hand, we realise that there is another side to us, and, consequently, another story to be told. This is our story from the outside. The story other people would tell of us. Again, the precise details of this story will depend on who the other person is. But certain core themes are clearly there to be told irrespective of who tells them. And one prominent strand of this story revolves around the theme of our ultimate insignificance. As a species we are finite, partial creatures, inhabiting an unremarkable planet in an unremarkable galaxy. We have been around for an infinitesimally small proportion of the life of the universe, and even the best estimates for our continuation dont give us too much longer in the cosmic scheme of things. None of us, not even the cleverest, really understands where we came from the origin of the universe we inhabit is necessarily a mystery to us. And, as far as we can tell, the fate of this universe we inhabit is heat death an unchanging state where all the complex structures in the universe have broken down into their simple constituents protons, neutrons, electrons, quarks, etc. which exist at a temperature approximating absolute zero. No life, no light, no change for ever and ever.

And, individually, each one of us is a product of forces that we did not choose and which we only dimly understand. We were born at a time and of parents we did not choose. We were, therefore, bequeathed a certain genetic inheritance over which we have no control but which does, to a significant extent, have control over us. This inheritance determines, in part, the illnesses to which we are susceptible, and the limits of our intellectual, athletic and moral capacities. Not totally maybe, but enough. And we find ourselves born into an environment that will fill in whatever slack is left over by our genetic endowment, an environment that, again, we did not choose and over which we have little control, at least in our crucial formative years. The way we are, and what we do, are the results of our genes and our environment that, together, exert an influence over us of which we have only the most nebulous understanding. This is what existentialist philosophers such as Jean-Paul Sartre meant when they said we are