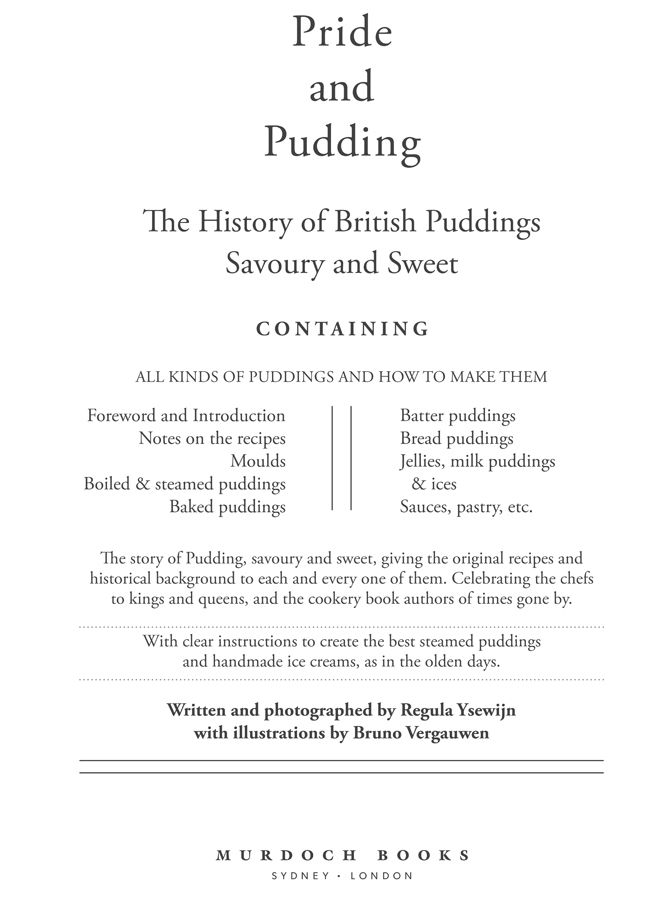

The great British pudding, versatile and wonderful in all its guises, has been a source of nourishment and delight since the days of the Roman occupation, and probably even before then. By faithfully recreating recipes from historical cookery texts and updating them for todays kitchens and ingredients, Regula Ysewijn has revived over 80 beautiful puddings for the modern home cook.

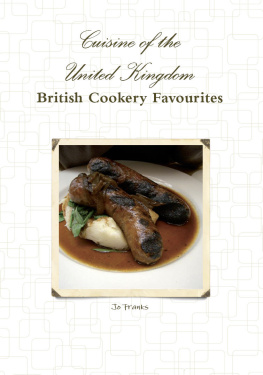

There are ancient savoury dishes such as the Scottish haggis or humble beef pudding, traditional sweet and savoury pies, pastries, jellies, ices, flummeries, junkets, jam roly-poly and, of course, the iconic Christmas pudding. Regula tells the story of each one, sharing the original recipe alongside her own version, while paying homage to the cooks, writers and moments in history that helped shape them.

REGULA YSEWIJN is a photographer and graphic designer from Belgium. She was born and raised in Antwerp where she went to art school and taught herself to cook. Her photography is inspired by the Dutch and Flemish Renaissance paintings she grew up with. She is the editor of the award-winning blog Miss Foodwise, which is dedicated to the subject of British food history and culture.

BRUNO VERGAUWEN is an illustrator, art director and creator of the beautiful illustrations in this book that help tell the story of British pudding.

This book is a tribute to the cookery writers of the past: the master chefs to kings and queens; the female cookbook writers of whom there are surprisingly plenty; the confectioners; the physicians; the poets; the cookery teachers; and those writers usually ladies, again who were driven by a profound passion for British food. Thank you for writing everything down.

Foreword

I love puddings. Sweet, savoury, boiled, steamed, baked and fried I will eat all of them. But when I say pudding, I mean PUDDING. I dont mean sweets, or desserts. In modern Britain, pudding has come to mean anything sweet at the end of a meal. Pudding is shorthand for many things I dont like: overly sweet cakes, Americanised brownies, fruit in anything but its most raw form

When I want a pudding, I want something solid, something fuelling, something so quintessentially British that it reinforces who I am at a very basic level; and yet its something that is so hard to define that in many ways those feelings are the definition.

Puddings had a bad press. Someone described as a pudding is overweight, rotund. If a substance is puddinglike, its solid, unyielding, stodgy. But theres something glorious about those very aspects of pudding. Pudding fills the stomach. Pudding salves the soul. Puddings very solidity grounds us, and its traditional round or oval shape is unflinchingly simple.

Pudding cuts right to the heart of Britishness. In the eighteenth century, when British cuisine was growing up and developing an identity, pudding was central to British gastronomy. It represented British simplicity, adaptability and perhaps a little bit of thuggishness in the face of the prevailing fashion for French food, criticised as fanciful, wasteful and full of deception. It appeared in satires as a symbol of the Empire, and illustrations as a symbol of family.

The Victorians had puddings for every occasion, recognising that no matter what class you were, and what position you occupied, with a pudding on the table you were all as one. The decline of the pudding, in some ways, echoes a confusion over what nationality and national identity means in the modern world, and whether they are even useful ideas at all.

Of course, we can read too much into it. But I do think that pudding and Britishness are intrinsically linked, and that were we to talk about getting a British, in the same way we in Britain talk about getting an Indian or getting a Chinese [meal], then what wed be getting would be a pudding. And Id be okay with that.

Prejudiced I may be, but Im pretty proud of my countrys pudding heritage. Youll see as you peruse this book, theres a lot more to pudding than meets the eye. For me, seeing pudding through the eyes of someone who has come to love it, despite the breadth of the North Sea between herself and Pudding Central, is a glorious way to appreciate it even more. Delve in (preferably with a spoon), and enjoy. Heres to pudding!

Dr Annie Gray, food historian

Pudding & me

F or nearly two years, my life has revolved around the British pudding. A political pamphlet of the 1700s said, The Head of Man is like a Pudding (A Learned Dissertation on Dumpling, 1726) ; and on many occasions while writing this book my head did feel like a pudding. One with delightful air holes, speckled with currants and covered in rich eggy custard sauce.

The task of uncovering the history of the British pudding consisted of ploughing through about two hundred books: some historical and some written about history or people; some books were poems, diaries and political pamphlets. I started collecting the antique cookery books I couldnt consult online or at libraries; handwritten notebooks and postcards; looking for clues in every imaginable place. Then I set out to collect the original moulds in which these puddings had been made through the ages. Needless to say, when you are dealing with such rarities they take a long time to gather and a greedy bite out of your savings too.

But this wasnt all: the book needed pictures, and as I am a food and lifestyle photographer, I did the photography for my own book and the design for that matter and my husband, a talented illustrator, created the wicked illustrations that tell part of the story.

But the recipe shots all needed plates and things, and I wanted them all to be of English make, so I needed to collect those too. Burleigh, one of Englands oldest surviving potteries (with whom I have a lovely relationship), kindly sent me some pottery, and the rest I gathered from markets and the usual online sources.

This was going to be a fairly straightforward project: a pudding book, except it became a project that would be with me for two years, and one that would dictate my life and my dreams at times. It has been an education. And although my quest has occasionally been nerve-racking partly because I do not live in Britain, but mostly because I do not come from a scholarly background I would dip my spoon in this bowl again.