About the Authors

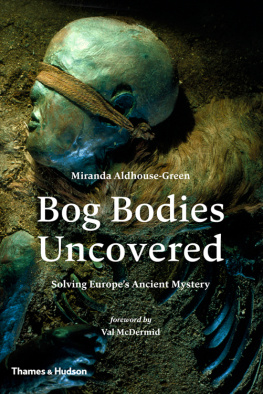

Miranda Aldhouse-Green is Professor Emeritus at Cardiff University. She specializes in the study of shamanism and archaeology of the Iron Age. She has published widely on the Celts and their world, including: The Celtic Myths, Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend and Exploring the World of the Druids.

Val McDermid is a bestselling novelist, recipient of the Gold Dagger award for Best Crime Novel of the Year and cofounder of the worlds largest crime fiction festival. Her novels have been translated into over thirty languages, selling more than eleven million copies worldwide. She recently released Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime (2014), an exploration of the science behind crime scene investigation.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

The Celtic Myths: A Guide to the Ancient Gods and Legends

Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend

The World of the Celts

The World of the Druids

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

We all carry our history under our skin. Where weve been, what weve done, how we lived. But for thousands of years that history, which our ancestors took to the grave, remained secret. Now, thanks to the giant leaps science has made in recent years, we can read those messages from the past. And finally, we can begin to peel back the layers and reveal the answers to mysteries that have confounded us for generations.

Among the most puzzling of those mysteries was that of the ancient bog bodies of Northern Europe. Buried in peat marshes and bogs, the unique environment meant their remains were preserved to a remarkable extent. That was exciting enough in itself for archaeologists and anthropologists. But what gradually became clear was that many of the bodies discovered generally by chance, by farmers and peat cutters had met violent deaths at the hands of others.

What crime writer wouldnt be fascinated by this phenomenon?

My own interest in the subject was piqued by an idea I had for a book that had its roots in the relatively recent past, a mere couple of hundred years ago. The Grave Tattoo was inspired by one fact and one rumour. The fact: the poet William Wordsworth and the Bounty mutineer Fletcher Christian went to school together in the Lake District. The rumour: Fletcher Christian didnt die on Pitcairn Island in the South Seas he returned to England, where he was sheltered from the forces of law and order by his friends and family. I began to build a present-day thriller round these historic events, but I needed something dramatic to kick-start the story.

I remembered seeing the recovered bog body known as Lindow Man on display in Manchester Museum in the late 1980s. Id been astonished at the degree of preservation it displayed, and the amount of information scientists had been able to garner from it. I wondered if a body that had only been in a bog for two hundred years could reveal even more.

I soon discovered how forensic techniques had evolved and are still evolving to provide data on everything from the diet these people consumed to the places where they lived and travelled while they were alive. Analysis of teeth and bones gives us an astonishingly detailed timeline of their movements. Thanks to mass spectrometry, now we can even tell where their mothers were living when they were pregnant. Facial reconstruction experts reveal what these people looked like in life. And we can uncover the violence with which they met their deaths. All perfect grist to the mill for my fiction. Because I get to make up the bits between the science, the pieces of the puzzle we cant quite grasp.

What we cant know are the underlying reasons behind the facts. But by learning all we can, its possible to come up with coherent theories that make sense of what we see. And thats where Miranda Aldhouse-Green has come to our aid. In this fascinating exploration of the phenomenon of bog bodies, she whets our appetite with the big picture of where, when and how these bodies began to turn up.

Then she examines the detail of a selection of the bodies, revealing how they gave up their secrets to us over the years and exposing the violence and apparent ritual that mark so many of their deaths.

Finally she delves under the shroud of mystery that surrounds them, exploring theories and suggesting histories for their lives that make sense of their deaths.

Human beings are curious by nature. We like answers. Thats one of the reasons I believe crime fiction is so popular. We can never know for certain how these bodies ended up with this very particular form of burial. The reasons are lost in a past that left no written records. All we can do is interrogate what is left. And that is what this book does so satisfyingly.

Prince or priest, reared for this moment your life a preparation for this death, an honour to appease the thirsty Gods for Tarainis, the shattering head-blows, for Esus, the garrotte and slit throat, for Teutates, the face-down drowning.

GLADYS MARY COLES, LINDOW MAN

In 1969 Professor P.V. Glob, of the Museum of Prehistory at rhus in northern Denmark, published his now famous and seminal book The Bog People. In it he drew peoples attention to a dramatic archaeological phenomenon, the preservation of whole bodies from the remote past. Ancient human remains almost always survive only as skeletons. Mummified bodies from the arid deserts of Egypt, and frozen bodies, such as occur in the ice of Inuit lands of the far north, are exceptions. What Professor Glob did in his book was to make accessible an incredible archive of ancient human bodies from Europe. They were preserved because of the peculiar properties of the raised bogs in which they had been deposited after death.

Most of the ancient bog bodies belong to the Iron Age and Roman periods, between the 8th century BC and AD 400, although some Neolithic bog bodies have also been discovered (see ). They occur, naturally enough, in regions with large areas of raised bogland: Ireland, mainland Britain, the Netherlands, Denmark and northern Germany. During this time and in these regions, most dead people were disposed of by burning or by inhumation in dry graves. But occasionally, for some reason, communities chose instead to place their dead in marshes, often in voids left by the extraction of peat or iron ore. What is more, there is forensic evidence that these bog people met untimely, often violent deaths involving a third party. In other words, they were done to death by others: murdered, executed or even ritually killed.

The peat bog at Haraldskaer in central Jutland, where the body of a middle-aged woman was pinned down with hurdles, after she was hanged, in the early 5th century BC.

Bogs were and are special places, miasmic and fearsome. They hover in the tween space between land and water: they are both and they are neither. They cannot be cultivated like normal land and they support vegetation peculiar to themselves. They may look innocent but can trap the unwary into a horrific and lingering death by slow, inevitable immersion. Such is the climax of Sir Arthur Conan Doyles Sherlock Holmes tale set on Dartmoor in southwest England,

Next page