Acknowledgments

This book could not have been begun or completed without the generous help of many colleagues and friends. Paul R. Hyams, Oren Falk, Thomas D. Hill, and Samantha Zacher offered prodigious insight and encouragement as I untangled the intricacies of medieval death and politics. Christopher Bailey, Cynthia Turner Camp, and Ionu Epurescu-Pascovici provided extensive, thought-provoking critiques of early drafts; and discussions with Andrew Galloway, Carol Kaske, Masha Raskolnikov, and Carin Ruff invariably inspired new avenues for exploration. The faculty and students at Trinity University have shown unwavering enthusiasm for my work, and Trinitys faculty research grants were vital to this project. My colleagues in the History Department have been especially helpful: John McCusker, Kenneth Loiselle, Aaron Navarro, and Joy Rohde offered valuable advice on my work in progress; and Don Clark, Anene Ejikeme, Alan Kownslar, Carey Latimore, David Lesch, and Linda Salvucci have been unfailingly supportive. I am indebted to Jeremy Donald, Amy Roberson, Tony Infante, and Eunice Herrington for their assistance in navigating maps, books, and all things administrative. I have also benefited enormously from the feedback I received from participants at conferences where I presented preliminary work, notably the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists, the Charles Homer Haskins Society, the International Medieval Congresses at Kalamazoo and at Leeds, the Fiske Conference on Medieval Icelandic Studies, and Cornell Universitys European History Colloquium. Conversations with Helen Foxhall-Forbes, Stefan Jurasinski, Dan OGorman, Lisi Oliver, Andy Rabin, and Elaine Treharne have been particularly stimulating, and Jay Paul Gatess expertise has been indispensable. It has been a genuine pleasure to work with Suzanne Rancourt at the University of Toronto Press, whose enthusiasm and professionalism have helped bring this project to fruition. Barb Porter saw the book safely through production, and the copy-editing skills of James Leahy and Bridget Cooley were most welcome as I prepared the final manuscript. Heartfelt thanks are also due to Dianne Ferriss, Tricia Har, Sarah Harlan-Haughey, Leigh Harrison, Curtis Jirsa, Johanna Kramer, Jessica Metzler, Jimmy Schryver, Colleen Slater, Misty Urban, Jennifer Watkins, and Sarah and James Disley. Finally, I am immeasurably grateful to Marcia and Robert Marafioti, Elise and Paul Yanon, Bea Fogelman, and Michael Paul Simons, who have endured more than their fair share of medieval exhumation, mutilation, and corpses. Their constant support and encouragement have made this book possible.

The Kings Body

Tables and Figures

Tables

Figures

Abbreviations

lfric, CH I lfric of Eynsham, Catholic Homilies: First Series, cited by homily and line

lfric, LS I and LS II lfric of Eynsham, Lives of Saints, cited by volume, homily, and line

Alfred 5, VIII thelred 1.1, etc. Anglo-Saxon laws: Liebermann, Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen, vol. 1, cited by code and chapter

ASC A Bately, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: MS A, cited by annal year

ASC B Taylor, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: MS B, cited by annal year

ASC C OBrien OKeeffe, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: MS C, cited by annal year

ASC D Cubbin, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: MS D, cited by annal year

ASC E Irvine, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: MS E, cited by annal year

ASC F Baker, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: MS F, cited by annal year

B., Vita Dunstani Winterbottom and Lapidge, Early Lives of St Dunstan, cited by page

Bede, HE Ecclesiastical History of the English People, cited by book and chapter

Bosworth-Toller Toller, An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary Based on the Manuscript Collections of the Late Joseph Bosworth, cited by page

Byrhtferth, Vita Oswaldi Lapidge, Byrhtferth of Ramsey, cited by page

De Antiquitate Scott, Early History of Glastonbury, cited by page

De Miraculis Sancti Eadmundi Thomas, Memorials of St. Edmunds, vol. 1, cited by page

EETS Early English Text Society

Encomium Campbell, Encomium Emmae Reginae, cited by page

JW John of Worcester, Chronicle, vol. 2, cited by page

MS manuscript

MR Mercian Register, cited by ASC manuscript and annal year

PL Migne, Patrologia Latina, cited by volume and column

S Sawyer, Anglo-Saxon Charters, cited by charter number

Vita dwardi Barlow, The Life of King Edward, cited by page

Whitelock, EHD I Whitelock, English Historical Documents, cited by page and item number

William of Malmesbury, GP Gesta Pontificum Anglorum, vol. 1, cited by book, chapter, and section

William of Malmesbury, GR Gesta Regum Anglorum, vol. 1, cited by book, chapter, and section

William of Malmesbury, Saints Lives, cited by book, chapter, Vita Dunstani and section

William of Poitiers, GG Gesta Guillelmi, cited by page

Introduction: The Politics of Royal Burial in Late Anglo-Saxon England

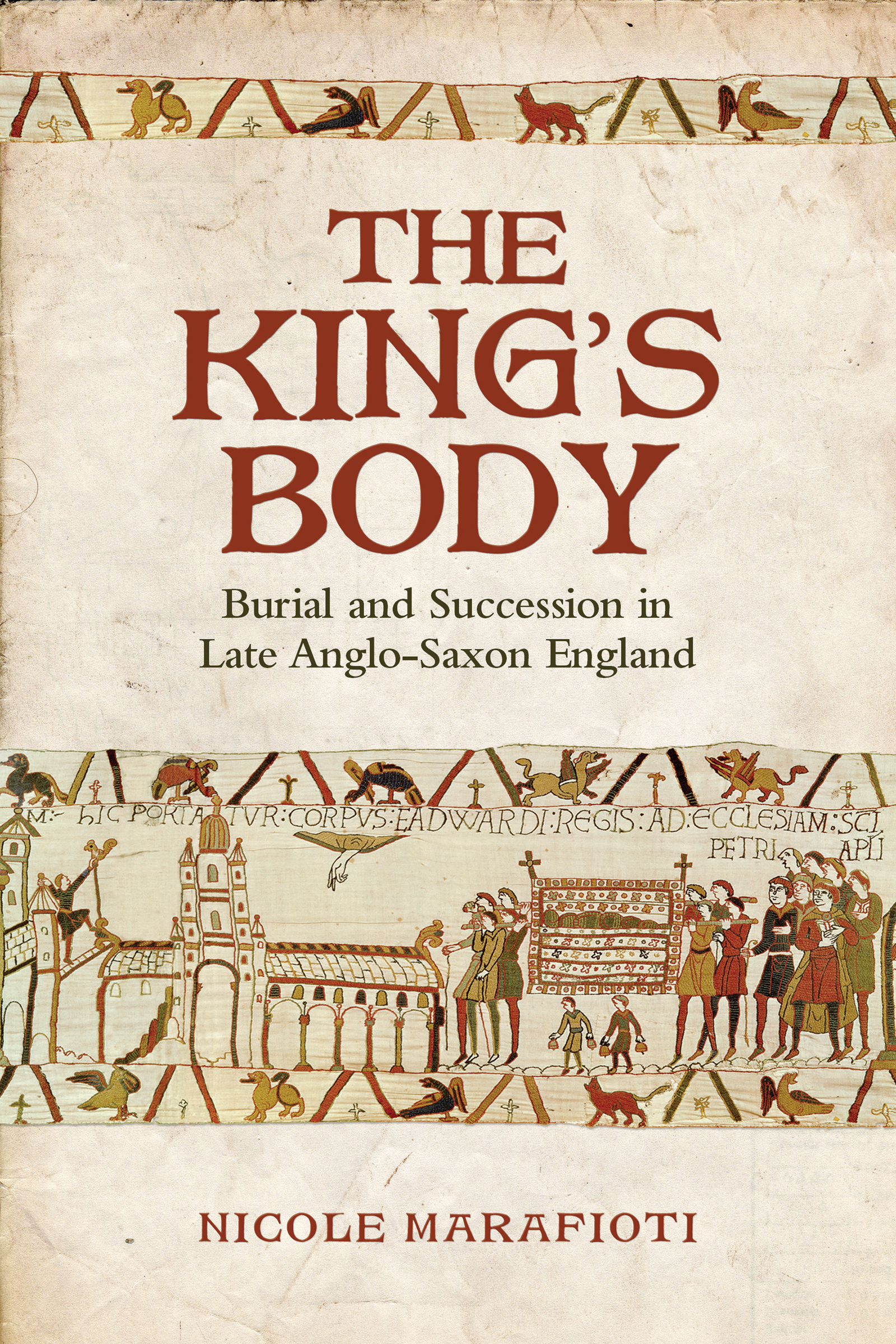

On 5 January 1066, Edward the Confessor died in his palace at Westminster. A few years later, the kings anonymous biographer produced the following account of his burial:

The funeral rites were arranged with royal expense and honour, as was fitting, and with the infinite mourning of all. They carried his blessed remains from his palace home into the church of God, and offered prayers and sighs along with the psalms, all that day and the following night. Meanwhile, when the day of the mournful celebration dawned, they blessed the funeral office they were to conduct with the singing of masses and relief of the poor. And so, the body was buried before the altar of St Peter the Apostle, washed in the nations tears, in the sight of God.

The authors foremost purpose in this passage was to illustrate the countrys grief at the loss of its beloved king, but he incidentally provided one of the few existing descriptions of an Anglo-Saxon royal funeral. We learn from this passage that Edwards body was publicly carried into its burial church, where mourners kept vigil until it was interred before the high altar the next day. We are told that the funeral office was accompanied by masses and the distribution of alms, all conducted with the honour and expense worthy of a king. We may also assume that a considerable number of mourners were present, including prominent laypeople who accompanied the body from the palace and clergymen who prayed and kept vigil over the royal remains. Yet while this excerpt provides an exceptionally detailed account of the burial of an eleventh-century English king, there were still aspects of the funeral that the author did not address. Who exactly was present? How was the body displayed? What sort of memorialization did the king receive afterwards? Although Edwards biographer showed considerable interest in the liturgical and processional aspects of the kings funeral, he found few of its mundane elements worth relating.

This silence is emblematic of most depictions of Anglo-Saxon royal death. Unlike Continental chroniclers, who regularly provided detailed accounts of rulers funerals, tombs, and bodies, Insular authors shied away from explicit descriptions of their dead kings. Most pre-Conquest English texts offered few details about royal burial and memorialization, simply noting where a monarch died and where his grave was. However, despite their cursory treatment in contemporary writings, kings funerals and tombs were not modest or obscure. As royalty, kings received privileged burial inside churches alongside abbots, bishops, and saints; as influential and wealthy Christians, they benefited from memorial masses and inclusion in monastic