BY ERNST H. KANTOROWICZ

L.C. Card No. 57-5448

D. M.

PREFACE

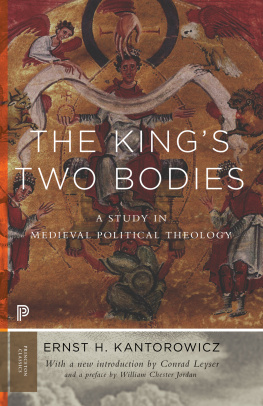

AT the beginning of this book stands a conversation held twelve years ago with my friend MAX RADIN (then John H. Boalt Professor of Law, at Berkeley) in his tiny office in Boalt Hall, brimful floor to ceiling and door to window of books, papers, folders, notes--and life. To bait him with a question and get him off to an always stimulating and amusing talk was not a labor of Hercules. One day I found in my mail an offprint from a liturgical periodical published by a Benedictine Abbey in the United States, which bore the publisher's imprint: The Order of St. Benedict, Inc. To a scholar coming from the European Continent and not trained in the refinements of Anglo-American legal thinking, nothing could have been more baffling than to find the abbreviation Inc., customary with business and other corporations, attached to the venerable community founded by St. Benedict on the rock of Montecassino in the very year in which Justinian abolished the Platonic Academy in Athens. Upon my inquiry, Max Radin informed me that indeed the monastic congregations were incorporated in this country, that the same was true with the dioceses of the Roman Church, and that, for example, the Archbishop of San Francisco could figure, in the language of the Law, as a "Corporation sole"--a topic which turned our conversation at once to Maitland's famous studies on that subject, to the abstract "Crown" as a corporation, to the curious legal fiction of the "King's Two Bodies" as developed in Elizabethan England, to Shakespeare's Richard II, and to certain mediaeval antecedents of the "abstract King." In other words, we had a good conversation, the kind of talk you would always yearn for and to which Max Radin was an ideal partner.

When shortly thereafter I was asked to contribute to a volume of essays in honor of Max Radin on his retirement, I could do no better than submit an essay on the "King's Two Bodies" (parts of Chapters I-III, and a section of Chapter IV), a paper of which he himself was, so to speak, a co-author or at least the illegitimate father. The Festschrift unfortunately never materialized. The contributions were returned to their authors, and though displeased by the fact that a well-deserved recognition was withheld from my friend, I was nevertheless not unhappy to see my manuscript back because in the meantime I had enlarged both my views

-vii-

and my material on the subject. I decided to publish my paper separately and dedicate it to Max Radin (then a temporary member of the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton) on his 70th birthday, in the Spring of 1950. Personal affairs such as the exasperating struggle against the Regents of the University of California as well as other duties prevented me from laying my gift into the hands of my friend. Max Radin died on June 22, 1950, and the study, destined to elicit his criticisms, his comments, and his broad laughter, serves now to honor his memory.

In its present, final form, this study has considerably outgrown the original plan, which was merely to point out a number of mediaeval antecedents or parallels to the legal tenet of the King's Two Bodies. It has gradually turned, as the subtitle suggests, into a "Study in Mediaeval Political Theology," which had not at all been the original intention. Such as it now stands, this study may be taken among other things as an attempt to understand and, if possible, demonstrate how, by what means and methods, certain axioms of a political theology which mutatis mutandis was to remain valid until the twentieth century, began to be developed during the later Middle Ages. It would go much too far, however, to assume that the author felt tempted to investigate the emergence of some of the idols of modern political religions merely on account of the horrifying experience of our own time in which whole nations, the largest and the smallest, fell prey to the weirdest dogmas and in which political theologisms became genuine obsessions defying in many cases the rudiments of human and political reason. Admittedly, the author was not unaware of the later aberrations; in fact, he became the more conscious of certain ideological gossamers the more he expanded and deepened his knowledge of the early development. It seems necessary, however, to stress the fact that considerations of that kind belonged to afterthoughts, resulting from the present investigation and not causing it or determining its course. The fascination emanating as usual from the historical material itself prevailed over any desire of practical or moral application and, needless to say, preceded any afterthought. This study deals with certain cyphers of the sovereign state and its perpetuity (Crown, Dignity, Patria, and others) exclusively from

-viii-

the point of view of presenting political creeds such as they were understood in their initial stage and at a time when they served as a vehicle for putting the early modern commonwealths on their own feet.

Since in this study a single strand of a very complicated texture has been isolated, the author cannot claim to have demonstrated in any completeness the problem of what has been called "The Myth of the State" ( Ernst Cassirer). The study may be none the less a contribution to this greater problem although it is restricted to one leading idea, the fiction of the King's Two Bodies, its transformations, implications, and radiations. By thus restricting his subject, the author hopes to have avoided, at least to some extent, certain dangers customary with some all-too-sweeping and ambitious studies in the history of ideas: loss of control over topics, material, and facts; vagueness of language and argument; unsubstantiated generalizations; and lack of tension resulting from tedious repetitions. The tenet of the King's Two Bodies and its history served in this case as a unifying principle easing the assemblage and selection of facts as well as their synthesis.

The origin of this study will explain how it happened that the author swerved again (as in his study on the Laudes) from the normal tracks of the mediaeval historian and broke through the fences, this time, of mediaeval Law, for which he was not prepared by his training. For this trespass he owes apologies to the professional jurist who, undoubtedly, will find many a flaw in this presentation, although the author himself is aware of some of the more likely shortcomings: overlaboring of texts on the one hand, missing of salient points on the other. But those are the hazards to which the outsider will usually expose himself; he will have to pay the fine for intruding into the enclosure of a sister-discipline. The incompleteness of sources is still another point in need of apology. Every student laboring in the vineyard of mediaeval Law will be painfully aware of the difficulty of laying hands on even the most important authors whose works, so far as they are published at all (there is, for example, no edition of the most influential canonist of the late twelfth century, Huguccio of Pisa), are available only in the both rare and antiquated sixteenth-century prints. Consultations of the Law Libraries at Berkeley, Columbia, and Harvard; the understanding kindness of the head of the Law