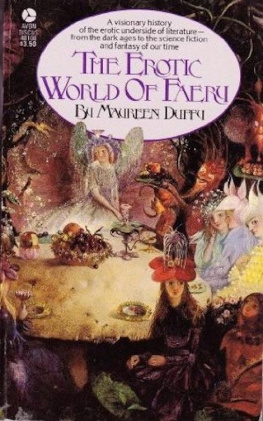

A book this length which treats of a subject this size must necessarily be superficial. Each chapter could have been a book in itself and even then there would have been much left out. I have not tried to proceed in strict chronological order but by themes which presented themselves only roughly by centuries. This means that Perrault will be found with Grimm and company among the fairy stories, not at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

What I have done is to provide an introduction, suggestions for further work and, I hope, to open up a subject to public speculation which whether in the hands of folklorists or literary critics has remained closed for too long.

This is an unashamedly popularizing effort and therefore it is full of assertions and simplifications. No doubt I have made mistakes of detail but I do not think they affect the truth of the main argument. I would rather make those mistakes than say nothing. I am aware too that there will be great resistance to many of my suggestions, for I am concerned with unconscious processes which themselves provoke repression and resistance in all of us.

No writer in this field can be unaware of a tremendous debt to the work of K. M. Briggs and I should like to acknowledge my own while firmly pointing out that Dr. Briggs is in no way responsible for the use to which I have put her researches in English folklore, or for the conclusions, which are entirely mine. I did not, alas, have the benefit of her excellent DictionaryofBritishFolklore which was published after the major part of the book had been written.

My gratitude to the special folklore collection at Kensington and Chelsea Central Library is enormous, as is my debt to Robert Cook, who transcribed a very difficult manuscript. I should also like to thank Jane Osborn for many helpful editorial suggestions.

TheBackgroundtoFayrie

The fairies are as immortal as the human beings who created them. They have been known to all times and all races as far as we have records. In the second half of the twentieth century they have held up the building of roads in Ireland that threatened their dwelling places; their dwarf figures look back at us in statuette from Egyptian tombs and now with the first rockets we have sent them ahead of us, much as they journeyed to settle the New World with the Pilgrim Fathers, exploding like a sun-burst peapod through space, colonizing and proliferating in all their recognizable manifestations: little green men; tall wan but very beautiful humanoids; hags and vamps; bodiless powers; all monstrous children of the serpent; red and blue devils; lost civilizations; the dead and all the legions of the supernatural.

However, unless one has a lifetime to spare, and the terrifying nineteenth-century industry and energy of a James George Fraser whose TheGoldenBough is a kind of GreatEastern or Menai bridge to anthropology, some small area has to be chalked out of a seemingly limitless field of speculation. The fairies for this book then will be those of the last fifteen hundred years in the British Isles.

This raises immediately the justifiable question that could well have been the rejoinder to Barries, Do you believe in fairies? What is a fairy? My first answer is: anything of an extra-human nature not within the Christian fold, with the exception of the diabolics who were taken over by the Church much as human children were thought to be spirited away to fairyland; or as a thirteenth-century Latin poem has it:

Ghosts and Fauns,

Nymphs and Sirens, Hamadryads,

Satyrs and ye Household Gods

under which dignified classical pseudonyms we recognize brownies, fairies, elves, pucks and all the rout of British enchantment.

TheChurchandtheFairies

Until the edict of Constantine in A.D . 331 ordering the destruction of all heathen temples, religious toleration had been the norm rather than the exception in human practice. Neither the Egyptians, Persians, Romans nor Greeks tried to force the worship of their pantheons on subject peoples nor uniformly on their own people. Eagerly they saw correspondences between their own and other mythologies and adopted other rites to fill a spiritual gap. Late Rome enjoyed the presence of Isis of Egypt and Mithras of Persia as well as Jesus of Judea. The goddess of love was equally recognizable as Venus, Aphrodite or Astarte. Diodorus Siculus describing a huge stone circle in the middle of Britain which may well have been Stonehenge calls it the Britons Temple of Apollo. immigrants, slaves, soldiers and whole nations on the move. They circulated in more sophisticated artistic forms, literary and visual, among the educated, and as songs, recitations and icons among the illiterate. Any study of Romano-British inscriptions alone would convince of the variety of myths currently available in even a small island on the fringe of the empire. Though the various religions no doubt competed among themselves for the overt allegiance of their disciples they were not exclusive. A grave stele might bear the names of both classical and eastern or Celtic divinities.

Historicity, which is to religion what naturalism is to art, demanded another response. The Christian god with the jealousy of his Jewish origin pushed to the extreme (no longer Thou shalt have no other gods before me but There is no other god) logically required the suppression of all other mythologies like a cuckoo in the mythopoeic nest. The Christ was an almost contemporary with a documented biography unlike the hero founders of other religions. Ravenously Christianity craved mankinds undivided emotional attention.

It may be objected against the general religious tolerance of the Roman empire that the early Christians were martyred for their beliefs. Their own technical inability to recognize the validity of other religious experience put them in this position. In permitting all kinds of worship while insisting on allegiance to the divine emperor, the father of all and therefore authority incarnate, the Roman empire tacitly recognized that all gods and theogonies were manifestations of the human psyche as well as anticipating modern ideas on the paternalism of society. The refusal to render unto Caesar constituted a family rebellion which would undoubtedly bring the sword and divide son against father, brother against brother. Identified finally with the emperor, Christianity became as autocratic as the traditional Victorian father.

Yet in place of infinite variety of symbol and story it offered a very narrow range of possible emotional and artistic experience. There were the facts set for ever by an O latest born and loveliest vision far, the Christian raconteur was driven to St. Lawrences griddle or St. Catherines wheel. Any attempt to fantasize on the life of Christ might well lead to the stake.

The Christian Church is usually given the credit for being the only institution to survive when barbaric hordes overwhelmed the Roman empire producing what is known as the Dark Ages, but this is a conclusion based on the Churchs own naturally rather biased post hoc propter hoc appraisal backed up by the doctrine of the survival of the fittest. Had classical Greek civilization survived the onslaught of Persians, Romans and internecine conflict we might be more inclined to think that social institutions follow biological principles. We dont know what we may have lost through the triumph of the Christian Church any more than we know what English literature may regret in the death of John Keats at twenty-five. It may be that the artistic paucity of the centuries from A.D . 300 to 1000 is as much the result of extreme theoconcentricity as of constant warfare.