SHAMANISM

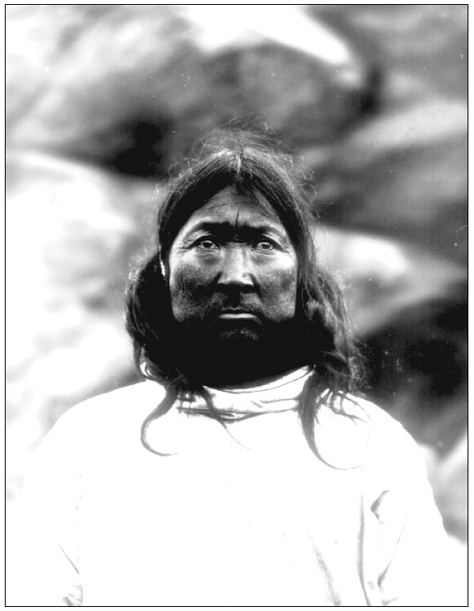

The angakkoq Ajukutok from Ammassalik, east Greenland. Born about 1864, he was later baptised. Photographed by Th. N. Krabbe, 13 September 1908. National Museum of Denmark, Department of Ethnography.

SHAMANISM

Traditional and Contemporary Approaches to

the Mastery of Spirits and Healing

Merete Demant Jakobsen

Berghahn Books

New York Oxford

First published in 1999 by

Berghahn Books

1999 Merete Demant Jakobsen

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form

or by any means without the written permission

of Berghahn Books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jakobsen, Merete Demant.

Shamanism : traditional and contemporary approaches to the mastery of spirits and healing / Merete Demant Jakobsen.

p. cm. -

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-57181-994-0 (hardback: alk. paper).

ISBN 1-57181-195-8 (paperback: alk. paper).

1. Shamanism--Greenland. 2. New Age movement--Greenland. 3. Greenland--Religion. I. Title.

BL2370.S5J35 1999

299'.7812--dc21 | 98-4193 |

| CIP |

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from

the British Library.

Printed in the United States on acid-free paper

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the following: first and foremost, all the anonymous course participants who entrusted me with their spiritual experiences. Dr Schuyler Jones and Dr Donald Tayler of the Pitt-Rivers Museum, Oxford; Professor I.M. Lewis, of the London School of Economics; Kirsten Thisted, of Copenhagen University; Poul Mrk and Rolf Gilberg, of the National Museum, Copenhgen; author Jens Rosing; artists Ib Geertsen and Bodil Kaalund; Professor Lydia Black and Professor Richard Pierce of the University of Alaska, Fairbanks; the Librarian and staff of the Balfour Library, Oxford; the Librarian of the Tylor Library, Oxford; Bodil Valentiner, Librarian of the National Museum Library, Copenhagen; The Librarian and staff of the Bodleian Library, Oxford; the President and Fellows of Wolfson College, Oxford; and The Danish Research Academy. Last but not least, my partner, Richard Ramsey, for his patient support and proof-reading, and our two rescued greyhounds, Ricky and Missy, who contributed to keeping my spirits high.

PREFACE

When I decided to write on the shaman, I was aware that I was venturing into a difficult and very sensitive area of research. Although there had been an explosion of interest during the previous two decades in the role of the shaman in the West and numbers of books of various depth had appeared, I still felt that my special area of interest, the Greenlandic shaman or angakkoq, was not usually represented in the literature on shamanism which was available in English. I therefore set myself the task of writing on the Greenlandic shaman utilising some sources that had only appeared in Danish.

To capture the nature of the angakkoq is a challenge. What is available is a variety of sources produced by narrators who describe not only the behaviour of different angakkut but also voice their own approach to the angakkoq and his relationship to the spirit world. I have, however, used descriptions that I hope through their diversity of opinions on the role of the angakkoq ultimately draw a picture of this mediator between his society and the world of the spirits.

My interest in the traditional Greenlandic belief system started with a chance visit to the Tukk theatre in 1980. This theatre, situated on the rough west coastline of Jutland in Denmark, was created with the intention of educating young Greenlandic actors and helping them to re-establish contact with their roots, the traditional beliefs in spirits, and the mythology, but in a form that was a mixture of those old traditions and the experiences of the young Greenlander in the modern Westernised society that Greenland, in many ways, had become. As far as I have been able to establish, however, traditional shamanism has not been revived in Greenland.

The attempt of the Tukk theatre to present a different kind of spirituality was an eye-opener to me. Participating in some of the theatres courses, I became highly interested in Greenlandic mythology, in which the role of the shaman and the spirit world play an important part. In the early eighties I wrote a masters thesis in Danish literature where I analysed a modern Danish writers usage of the Greenlandic spiritual world to illustrate our de-spirited modern society. My conclusion was that this writer, Vagn Lundbye, saw himself as a sort of modern version of a shaman, as a mediator between a non-inspired Danish society and a highly inspired traditional Greenlandic one. I was unaware as I wrote that a modern version of shamanism, known as core-shamanism, created by Michael Harner, was starting to spread in the United States.

As I followed the development of the interest in shamanism in the West during the eighties and nineties, as presented in journals, books and courses, it became clear to me that there were significant differences between the shamanism that had derived from the traditional Arctic region and neo-shamanism, especially where the relationship to the spirits was concerned. I therefore decided to participate in a variety of courses to examine that difference. The fieldwork material in this book is based on the courses of one particular course organiser. He was fully informed of my intention to conduct research and to compare the courses with the traditional shamanism represented by the angakkoq. I undertook my research with a sense of profound respect for the valuable experiences of the participants and was very careful never to take any notes during the participants descriptions of their journeys where permission was not first given. The examples of journeys are therefore based on my own experiences and the accounts given to me during the interviews I conducted.

One of the aspects of New Age thinking that has caused me concern over the years is a reluctance to face the negative aspects of spirituality. There is an old Nordic legend which describes a saint who was carefully building a church during the day but each night a troll came and tore it down. After this had gone on for some time, the saint decided to hide during the night and find out who the culprit was. Hearing the trolls name, the saint managed to face the troll, using the name as his weapon, to put an end to the nightly destruction and get on with building his church. The un-named dark side can play all kinds of havoc or, in other words, the sense of power achieved in a course might overwhelm the present-day healer as it did some of the angakkut.

Merete Demant Jakobsen

Oxford

INTRODUCTION

The otherness of the shamanic world-view has fascinated and appalled researchers and missionaries for centuries, just as it now fascinates modern urban Westerners. The increase in the number of shamanic courses over the last few years is just one indication of how much interest exists in the role of the shaman. I have chosen to focus on the concepts of mastery of spirits and healing from a shamanic perspective among the Greenlandic people, with a few examples from other Eskimo peoples, and the New Age version of shamanism called neo-shamanism, core-shamanism or urban shamanism.