Buddhist Fury

Buddhist Fury

Religion and Violence in

Southern Thailand

MICHAEL K. JERRYSON

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further

Oxford Universitys objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 2011 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jerryson, Michael K.

Buddhist fury : religion and violence in southern Thailand / Michael K. Jerryson

p. cm.

Includes biliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-19-979323-5; 978-0-19-979324-2 (pbk.)

1. Buddhism and politicsThailand, Southern. 2. ViolenceReligious aspectsBuddhism.

3. Thailand, SouthernPolitics and government21st century. I. Title.

BQ554.J47 2011

294.337273dc22 2010040326

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

CONTENTS

FIGURES AND TABLES

Buddhist Fury

It is also an erroneous idea to suppose that the Buddha condemned all wars and people whose business it was to wage war. Many instances could be quoted to prove that the Buddha recognized the necessity of defensive war, and such may also be inferred from parts of the following allocution itself. What the Buddha did condemn was that spirit miscalled Militarism, but which is really intolerant and unreasoning hatred, vengeance, and savagery, which causes men to kill from sheer blood-lust, and a religion that tolerates such a brutish spirit is not worthy of the name of religion!

King Vajiravudh, Rama VI

We need to find peace, said a seventy-five-year-old southern Thai Buddhist monk I will call Ahn Pim during an interview at his monastery August 14, 2004. Ahn Pim was referring to the growing divide between Buddhists and Muslims in the region, which had suffered sporadic unclaimed attacks against monks, armed forces, teachers, workers, and pedestrians. His monastery is located in a region within Thailands three southernmost provinces that border Malaysia (smhangwat chydenphkhtai). Eight months before our January 2004 interview, the Thai government declared martial law in the three provinces of Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat. However, the Thai governments declaration, together with its policies and practices, proved ineffective in quelling the seemingly random bombings and murders. If anything, the imposition of martial law intensified the political nature of the conflict.

Among the many victims were Buddhist and Muslim rubber workers. The rubber industry was a major economic commodity for the region. Ahn Pim explained, When Muslims threaten Buddhists, sometimes Buddhists need to be violent in return. The people need to rise up and harvest the rubber trees. They need to unite and resist this form of extortion.

Since January 2004, there have been more than 4,100 deaths and 6,509 casualties attributed to the violence in the deep south. Although they are not the primary agents, Buddhist monks are armed participants in the southern Thai conflict. And, if the epigraph for this chapter suggests anything, it is that the Thai Buddhist views on violence are much like those in any other religious tradition. Violence becomes a religiously justifiable action so long as it is defensive. This seemingly sound qualification yields a slippery slope, for who sees themselves as true instigators of a conflict? In many ways, the focus of this book contrasts with the most general assumptions of Buddhist traditions and monasticism.

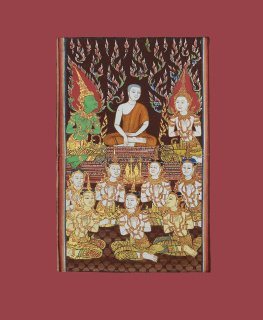

Buddhist monasticism entails the separation of ones self from lifes vulgarities. Theravda Buddhist traditions like Thai Buddhism involve the practice of young men taking temporary ordination for this very purpose. This is a time for them to separate themselves from the regular affairs of the world and their community and direct their time and attention to Buddhist teachings and monastic practices. In addition to intrapersonal merits, their ordination builds merit for their family and grants them social status in their community. Thais view Buddhist monasticism as a break from the regular habits and vices of life. It is commonly assumed that Buddhist monks live apart from everyday politics, corruption, and economic issues. As the fading lineage of Thai forest monks (thudong) reveals, the more a monk appears separate from society, the greater the social veneration. And, why not? A forest monk embodies the commonly held beliefs of what Buddhist monasticism should be.

It is, thus, a great shock for Thais to hear about monks equipping themselves with handguns or affiliating themselves with military activities. Monks are not immune to political tensions. One of the most recent examples of this is the Thai Buddhist monks divided affiliations during the violence that took place in Bangkok between March and May 2010. The involvement of Buddhist monks as both victims and agents of violence significantly alters the conflicts parameters; in particular, it strengthens a perceived religious dimension to the conflict.

While the conflict is distended with causes, actors, and motivations, there are some threads that stand out among the rest. The first of these is educationor specifically, the public recollection of the regions religious and political heritage. The Thai colonization of the Malay Muslim kingdom of Patani and its manipulation of public memory have resulted in the violent treatment of Malay Muslims, who are a religious and ethnic minority. The second of these threads is the relationship between the Thai State and Thai Buddhism. At the heart of this work is an

Thai Buddhist studies scholar Suwanna Satha-anand postulates that a Thai Buddhist hegemony allows Thai Buddhists to tolerate different religious groups. Hegemony always creates a comfortable space for the privileged; however, the Thai Buddhist hegemony is contested in the southern context. What I ultimately conclude through fieldwork and archival analysis is that the State-sangha connection furnishes a hegemonic script that subjugates, silences, and alienates the Malay Muslim minority, their history, and their identity. This hegemony fuels the Malay Muslim insurgency in the southern region. There is a panoply of studies that review the Malay Muslims, just as there are studies on the relationship between the Thai State and Thai sangha. However, this is the first study to assess the role of Thai Buddhist monks in a religio-political conflict and contributes to the study of Buddhist traditions and their relationship with warfare.

Next page